323 Old Earth Dogs

RECALLING OLD EARTH DOGS

by David Hancock

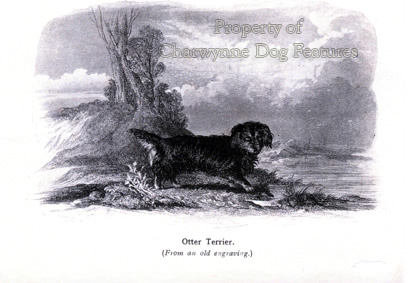

Our breeds of native terrier have not always been well-named or aptly recognised. We could so easily have had Cowley, Roseneath, Clydesdale, Paisley, Cheshire, Shropshire, Devon and Otter Terriers; recognition of breeds of dog so often relies on determined individuals as much as ancient type. I have heard it argued that what we now call the Wire-haired Fox Terrier is the type favoured by the Rev John Russell and what we call the Jack Russell Terrier (Parson Russell Terrier in the show rings) might be better called a Heinemann Terrier. Parson John was a founder member of the Kennel Club, judged Fox Terriers at KC shows and has been referred to as the 'father' of the Fox Terrier. Russell's comment on his first terrier 'Trump' was that she was : "The first and last terrier with cut ears and tail that I have ever owned." Purists could therefore argue that the terrier breed named after him must have an undocked tail!

Our breeds of native terrier have not always been well-named or aptly recognised. We could so easily have had Cowley, Roseneath, Clydesdale, Paisley, Cheshire, Shropshire, Devon and Otter Terriers; recognition of breeds of dog so often relies on determined individuals as much as ancient type. I have heard it argued that what we now call the Wire-haired Fox Terrier is the type favoured by the Rev John Russell and what we call the Jack Russell Terrier (Parson Russell Terrier in the show rings) might be better called a Heinemann Terrier. Parson John was a founder member of the Kennel Club, judged Fox Terriers at KC shows and has been referred to as the 'father' of the Fox Terrier. Russell's comment on his first terrier 'Trump' was that she was : "The first and last terrier with cut ears and tail that I have ever owned." Purists could therefore argue that the terrier breed named after him must have an undocked tail!

A long history is often claimed for breeds of terrier, but I doubt if terrier men in past centuries ever bothered much about pure breeding. In his The Book of all Terriers of 1971, John Marvin writes: "Despite claims made by writers who champion the antiquity of several of today's Terrier breeds, years of careful research have failed to disclose a single reference to any reproducible breed prior to 1800. In fact, the only deviations from the earliest descriptions are variations noted as to coat, size and legs."

In his Field Sports of 1760, terriers are described by William Daniel as being of two sorts, one of them rough, short-legged, long backed and very strong, usually black or light tan colour, mixed with white. The other was said to be smooth-haired and more pleasingly formed, with a shorter body and a more athletic appearance, usually reddish-brown or black with tan legs. Prototypes of subsequent breeds are hinted at there. French and German writers of previous centuries have made reference to dogs functioning as terriers, not just Dachshund types but Pinschers and Schnauzers too. We may have captured the terrier breed market but not the terrier function.

In Ireland, the unusual smoke-grey coat of the Kerry Blue Terrier has been linked with the Harlequin Pinschers of the soldiers of the House of Hesse, who were stationed there. In Kay's Portraits From Nature (c.1810) there is an illustration from Scotland of a Pinscher; the coastal areas of the Scottish Highlands contained men who served as mercenaries in German armies. The Pinscher may have been imported by them. As far as the German Hunt Terrier is concerned, the reverse may have happened. When I was working in Germany nearly forty years ago, an old German Forstmeisster told me that his grandfather had imported English hunt terriers to control vermin. International boundaries have never been barriers to the dog trade.

Terrier breeds which emerged in Britain in the 19th century, whatever their origin, are, with a few exceptions -- like the Border Terrier, markedly different in some respects nowadays from the stock shown at early dog shows. Some of these differences are displayed in even shorter legs, in breeds which already featured short legs, even longer muzzles (and narrower in Fox Terriers) and greater cloddiness, as in the show Sealyham. But even more noticeable, are the far heavier coats, in today's Scottish Terrier for example, and, sadly in so many terrier breeds, upright shoulders and no falling away at the croup.

These two latter features are responsible for the greatly-abbreviated front and rear stride in these breeds, resulting in movement falsely described by some as a "terrier action". This lack of extension, fore and aft, can never be acceptable in a sporting terrier, especially an earth-dog. Kennel Club recognition has undoubtedly brought uniformity to these breeds and perhaps greater beauty. But beauty, in a terrier, at the expense of function, is an empty gain. Function dictates form in quadrupeds and form contributes both to health and quality of life. I shudder when I hear a TV commentator at Crufts excitedly describing sporting terrier breeds on the move as "simply flowing over the ground". Millipedes flow over the ground; dogs, whatever their size, should stride.

Regrettably, exaggerations in dogs with a closed gene pool always end up exaggerating themselves. Outcrossing to restore true type may be regarded as sacrilege by conformists. But why, once attracted to a breed, not honour its true blueprint? Why betray its original type and true form? Sadly, most show breeders are extraordinarily conformist, even when true breed type in their favoured breed is threatened. Pedigree dog breeders and dog show judges often draw an undeserved awe from the general public; some are undeniably gifted, most are very obviously not. An experienced breeder, even to the KC, all too often means someone who has bred a lot of litters, whatever their quality. Judges, similarly, can progress if they have bred prolifically from their stock.

This insanity not only leads to false reputations being gained but far too many puppies being bred. No livestock judge at an agricultural show is ever chosen on the basis of how many calves or lambs he or she has bred. Pony and houndshow judges are chosen for their knowledge not their production line. The same criterion, if applied in the world of pure-bred dogs, would represent a giant step forward. Far too many dog breeds have been at the mercy of wallet-conscious, power-seeking puppy-producers posing as experts in their field. Terriers designed originally to work should never feature over-heavy coats, a cloddy build with little flexibility, ant-eater heads or limited extension when moving.

The early Sealyhams were prized for the coconut matting texture of their coats; the current breed standard demands a coat that is long, hard and wiry. The dogs I see in the ring have long, soft and wavy coats. Captain Jocelyn Lucas, who worked the breed, states, in his Pedigree Dog Breeding of 1925, "A hard coat is not only a show point, but also a working one, as soft-coated dogs generally hate brambles." Today's breed standard of the Wire-haired Fox Terrier asks for a coat that is dense with a very wiry texture. Just before the Second World War, Rowland Johns wrote, on the wire-haired variety, in his Our Friend the Fox Terrier, that: "The harder and more wiry the texture of the coat is the better. On no account should the dog look or feel woolly...". In the show ring I see soft woolly coats on many winning dogs.

Today's breed standard for the Scottish Terrier describes the coat as close-lying with a harsh outer coat. In his book on the breed, published seventy years ago, W L McCandlish set out the standard of that time. The coat was described as rather short (about 2"), intensely hard and wiry in texture; wave in the coat was described as a special fault. The Scottish Terriers that I see winning at shows have an abundance of coat -- well over four inches, with waviness, standing off from the body; so much for breed standards and a respect for a breed's heritage! The great Fox Terrier expert Rosslyn Bruce, in his book on the breed of 1950, writes: "The coat, or the outside covering or jacket, is that part of the Terrier which is perhaps the most difficult for the novice to grasp..." He might have included judges in that sentence.

Rosslyn Bruce warned against a too long-headed dog with a too short back; I see many winning dogs today featuring these two components. He was very specific on the subject of shoulders, stressing their need to be long and sloping, well laid back. He pointed out that: "Where the shoulders are well laid back the dog is at an advantage for work underground." With most sporting terriers in today's show ring, I find upright shoulders and, increasingly, short upper arms. Unless knowledgeable judges penalise this bad fault it will become a breed feature and be bred in for all time. Should we not keep faith with those who developed these splendid breeds for us?

In his book on the Fox Terrier, Rosslyn Bruce makes one statement which gladdens my heart: "...I say to the budding enthusiast: The first point to aim at in a terrier is "Character", the second "Character", and yet again the third essential is "Character"." Here is a man steeped in the exhibition world, member of the Kennel Club Committee and founder of the Smooth Fox Terrier Associ ation, having the wit and the perception to see what makes a terrier, in any age. It is tenacity, fortitude, fearlessness, dash and perky assertiveness which makes a terrier what it is, rather than perfection of form. But these qualities alone do not make a successful sporting terrier; such a dog needs the anatomy which allows it to perform its allotted task: the control of vermin above and below ground.

ation, having the wit and the perception to see what makes a terrier, in any age. It is tenacity, fortitude, fearlessness, dash and perky assertiveness which makes a terrier what it is, rather than perfection of form. But these qualities alone do not make a successful sporting terrier; such a dog needs the anatomy which allows it to perform its allotted task: the control of vermin above and below ground.

Breeders of show terriers, together with those who judge them, have a duty to respect the remarkable heritage behind their dogs. They may not want their terriers to go to ground but their dogs are not terriers unless they have the mental and physical qualities for such a task. The pioneer breeders handed these precious breeds down to us to safeguard in our lifetime. It will be sad indeed if future generations inherit terriers with soft wavy coats, a short-stepping gait and a complete absence of adventurous spirit. Such dogs belong in the Toy Group; they are neither sporting dogs nor terriers.

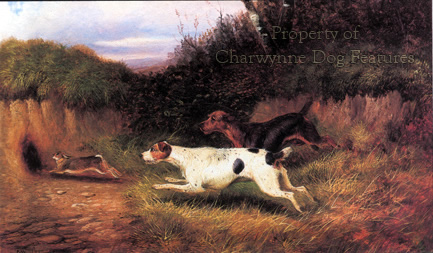

The early terriers had the weatherproof coat, the extension in their limbs which allowed them to function and the never-say-die attitude which made them invaluable to man in farms and factories alike. I have vivid memories, as a boy, of the wire netting going round the ricks and the terriers being loosed, to kill over 200 rats per rick despite the odd bite. No machine could ever do that -- or chemical. Gassing or poisoning is a dreadful way to control rats; terriers are fast and efficient. Anyone with a bored teenaged son should give him a terrier!