299 THE CONSTANCY OF CANINE COMPANIONSHIP

THE CONSTANCY OF CANINE COMPANIONSHIP

by David Hancock

.jpg)

There is something quite charming about seeing a small child accompanied, being protected too, by a much larger, and usually quite dedicated, dog. A lone adult with a dog as a companion makes much more of a social statement than otherwise - as so many artists have captured down the centuries. When I was in East Africa, I saw a bull-elephant that had been pushed out of the community of the herd through the ascendancy of a younger male. He lived a lonely solitary life until he died and was dubbed "El Wahido" as a result. I had more sympathy for him after once spending a year or so living just with my dogs for company. I was glad too that my dogs had each other. For just as we need human company as well as theirs, dogs need canine company as well as ours. Even scientists have come to appreciate the importance of canine company for humans living alone, without always being able to identify every reason for it. The huge advantage of the companionship provided by dogs is its constancy. What a joy to share your life with another living creature that takes you as you are, provides endless, selfless affection and asks for so little in return. Dogs seem to have the secret of life!

There is something quite charming about seeing a small child accompanied, being protected too, by a much larger, and usually quite dedicated, dog. A lone adult with a dog as a companion makes much more of a social statement than otherwise - as so many artists have captured down the centuries. When I was in East Africa, I saw a bull-elephant that had been pushed out of the community of the herd through the ascendancy of a younger male. He lived a lonely solitary life until he died and was dubbed "El Wahido" as a result. I had more sympathy for him after once spending a year or so living just with my dogs for company. I was glad too that my dogs had each other. For just as we need human company as well as theirs, dogs need canine company as well as ours. Even scientists have come to appreciate the importance of canine company for humans living alone, without always being able to identify every reason for it. The huge advantage of the companionship provided by dogs is its constancy. What a joy to share your life with another living creature that takes you as you are, provides endless, selfless affection and asks for so little in return. Dogs seem to have the secret of life!

.jpg)

Spending that year or so of living alone, with only my two dogs as companions made me aware of the uniqueness of a dog's companionship, especially the constancy of it. There are many of course who have spent any number of years doing likewise but in my case it was new and therefore more educational. I have been involved with dogs all my life, that is over fifty years, but always with the dogs in a working environment, or housed in an outhouse or with family being a higher priority. I thought that I had a great deal of knowledge and understanding of dogs from this but the last year of living closer to them than ever before and needing their companionship as much as they needed mine has really opened my eyes. With no other human to talk to in the house, no neighbours in my rather isolated country location and no social life away from work led to my spending much more time with my dogs, observing them more closely, understanding much better their very different philosophy of life and coming to acknowledge their little subtleties.

It became now much clearer to me how dogs think, react, anticipate and respond. I realised that they are far more sensitive than I had appreciated. I admit that I have been underestimating their capability, underrating their cleverness and undervaluing their potential...really throughout my life. I do wish that I had had the opportunity, the circumstances and the wit to have learned this a long time before. Yet when I browse through my library of books on dog-training, especially those on gundog training, I find that time and time again even the acknowledged experts in their field lack the basic understanding of the mind and instincts of the domestic dog. The expressions they use like "dog-breaking", "breaking to the gun" and "a touch of the whip" really offend me..jpg)

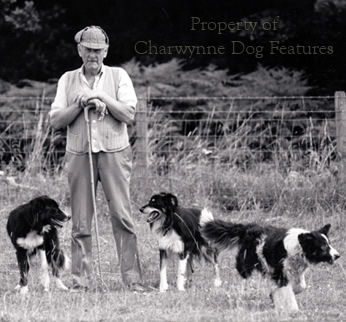

I subsequently became very envious of those who centuries ago used the cleverness of dogs in a most enlightened way, often to their benefit admittedly, but usually in a mutually-dependent relationship. I am thinking of the shepherd in the days when he lived with his sheep and his sheepdogs, of the humbler hunter sharing his primitive dwelling with lurcher and of the waterside hunter's partnership with his gifted water-dogs and guileful decoy-dogs. Such men were so close to their dogs, knew how clever and valuable they were and were wise enough to appreciate the full potential of their dogs. It is extremely rare in modern society for dog-owners to need their dogs so much and to be so close to them. We forget too how all dogs love to work, to be employed, to be useful, to give service. But how we underuse them! Look down at your sleeping dog with greater empathy.

I wonder if down the ages the articulate, the scholarly, the academic and the literate elements of our society haven't been allowed to have the field to themselves far, far too much. They feed off each other, read more than they experience, learn almost entirely from educated people and often distance themselves from unsophisticated wisdom, deeper understanding and more perceptive observation. Today the gundog fraternity know a great deal about the work of the Labrador Retriever and the Springer Spaniel, few of them have ever heard of the red decoy-dog or the great rough water-dog, animals far cleverer than the modern gundog. The much-quoted Dr Caius, who four centuries ago, wrote the first book on English dogs, was a scholar not a dog-man and much of what he wrote on dogs came from his not knowing he was having his leg pulled by the sportsmen of his day. Yet he is extensively quoted as being authoritative. Celebrated writers like "Stonehenge" and "Idstone" in the last century are regarded as the great canine experts of their day by far too many researchers. Men like these never lived with dogs as say a shepherd did in their times...where is the voice of the shepherd?

Even quite knowledgeable modern gundog authors write about training methods which can only stop dogs thinking for themselves and thereby failing to bring their powerful innate skills into play. Some dog-training "experts" seem to be advocating dogs with keys on their backs and a motor instead of a heart. Certainly their views on discipline horrify me and I recall the words of Mark Hayton of Ilkley, Yorkshire, trainer of some of the world's finest sheepdogs over thirty years: "It is not by the boot, the stick, the kennel and chain that a dog can be trained or made man's loyal friend but only by love. For those who understand no explanation is needed; for those who do not, no explanation will prevail." "Those who understand" are so often those who totally rely on the use of dogs for their livelihood rather than for sport or a pastime but are mainly those who have spent long hours alone with their dogs. The miner with his Whippet, the gypsy with his lurcher and the blind man with his guide-dog have a kinship with their dogs which is something special. Some old-time gamekeepers developed a similar rapport; many present-day gamekeepers seem to lack this extra dimension to their work with dogs. These words of mine are far removed from an indulgence in romanticising about times past or overlooking the need to have control over headstrong dogs; it is more a need to pass on to others the enlightenment which has come directly from a year spent in a new closeness to dogs.

After my year or so of living just with dogs for company I find I can now communicate with my dogs far better. By this I don't mean purely verbal communication. At that time, I carried out little trials in which for whole days I would not use my voice at all, but rely on the association of ideas through dress, gesture, activity, route and timetable. It was quite remarkable to discover that the spoken word was largely redundant. The dogs were nearly always ahead of me. For some years they have been telling me when other humans were around and when telephones were ringing and I obviously hadn't noticed, now they were reminding me of breaches in an established routine. Their powers of observation and then stored memory are really astounding. I needed to learn more lastingly too the degree to which we are sight-led whereas dogs utilise their powers of scent and hearing far, far more. We all acknowledge such facts but rarely give them their true significance, their proper perspective. Perhaps that's the difference between cleverness and wisdom; some of the wisest people I know are those closest to nature and its simplicities. AS A BOY.jpg)

Around fifty years ago I used to chat to an elderly man who had been a shepherd on Salisbury Plain for most of his working life. He didn't talk about the harshness of the weather, the loneliness of spending whole summers out on the plain or of the eternal difficulties of sheep farming. He talked of his greatly valued and much missed 'Bobtails', his herding dogs. He could recall the names of a score of dogs, especially the one that saved him in a snowdrift and the one that warned him of an unexploded shell. For me, that's the greatest value of dogs; they provide something that no other source can; they share their philosophy of life with you and accept yours; they are only interested in external matters and never indulge in self-pity, vanity or the human obsession with appearance. They do suffer from the latter however - especially the long-coated breeds!

The constant companionship of a dog leads to your knowing what provides it with spiritual contentment and striving to provide at least an element of that need. People who buy a gundog and then expect it to lie in front of the television all day end up with an extremely discontented dog and wonder why. People buy a dog from a guarding breed and then complain that it resents the dustman taking their rubbish away. People buy a small assertive terrier and then express surprise when it resents next door's cat coming into its garden. Educated people should keep in mind Dean Inge's wise words of eighty years ago: "The aim of education is the knowledge not of facts but of values." Appreciating the companionship of dogs is not some maudlin’ mawkish over-sentimental act of anthropomorphism. It is a combination of genuine affection, empathetic respect and compassionate care. It is a simple realization that dogs, through their selfless constancy of companionship, are actually ahead of us in the affection game - and they didn't need an expensive education to do so!