290 American Mastiffs

BULLBREEDS FROM THE AMERICAS

by David Hancock

The association between the Americas and the various breeds of mastiff-type dogs, i.e. those with modified brachycephalic (round-headed) skulls, is easy to underrate, until the fact that explorers and migrants took dogs with them on their travels is taken into account. In his excellent book 'The Labrador Retriever - The History...the People' of 1981, Richard Wolters relates how the Devonshire fishing communities settled in Avalon, Newfoundland with their black hunting dogs after sailing from England in the 16th century. He believes and may well be right that the Labrador Retriever was merely coming home when it came off ships in Poole harbour two centuries later. In similar vein I believe that the Nova Scotia Duck Tolling Retriever is the Red Decoy Dog of Britain exported and that the Chesapeake Bay Retriever is the Norfolk Retriever re-established in a new home, not surprisingly near Norfolk, Virginia.

The association between the Americas and the various breeds of mastiff-type dogs, i.e. those with modified brachycephalic (round-headed) skulls, is easy to underrate, until the fact that explorers and migrants took dogs with them on their travels is taken into account. In his excellent book 'The Labrador Retriever - The History...the People' of 1981, Richard Wolters relates how the Devonshire fishing communities settled in Avalon, Newfoundland with their black hunting dogs after sailing from England in the 16th century. He believes and may well be right that the Labrador Retriever was merely coming home when it came off ships in Poole harbour two centuries later. In similar vein I believe that the Nova Scotia Duck Tolling Retriever is the Red Decoy Dog of Britain exported and that the Chesapeake Bay Retriever is the Norfolk Retriever re-established in a new home, not surprisingly near Norfolk, Virginia.

In Central and South America, the Spanish and Portuguese colonists similarly took dogs of various types with them, either as hunting dogs or dogs of war. In both categories came the mastiffs, both the par force hounds or running mastiffs and the hunting mastiffs or seizing dogs. This has left us with the Fila Brasileiro in Brazil, the Dogo Argentino in Argentina (a classic running mastiff), the Perro Cimarron in Uruguay and the Gran Mastino de Borinquen in Puerto Rico. The Cuban Bloodhound was undoubtedly of mastiff type; the Bajan Biting Dog was also a holding or gripping breed. In Uruguay too there is a big white flock guarding breed very similar to the Spanish Mastiff; the Spaniards had settled most of the country by the late 18th century.

In North America most European breeds of dog have found their way to Canada and the United States. In his book on the American Pit BullTerrier of 1997, Louis Colby lists family after family which emigrated from Ireland, England and Wales, with their Bulldogs and Bull Terriers. In Canada, John and Lolly Wilkinson are still breeding their 'Original English Bulldogges' from stock found in a remote area of Nova Scotia. The early colonists and settlers in North America needed stock dogs and hunting dogs, with cattle-pinning dogs becoming an urgent requirement. Perhaps predictably, the American stockmen took the English Bulldogs being imported and developed them into the American Bulldog, a bigger, usually more active and certainly less equable breed.

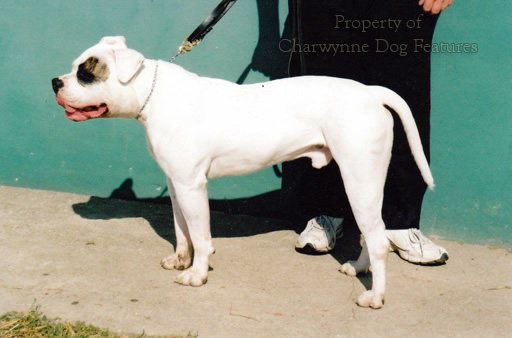

Variants of the Bulldog are bred in many places in the United States, with names like the Alapaha Blue Blood Bulldog, which is now a stabilised type, the Georgia Bulldog, very much like a more powerful 18th century English Bulldog, Old Country Bulldogs and Old English Whites. But the most numerous and the best known are called simply American Bulldogs. One of the better known breeders of such dogs was John D. Johnson of Summerville, Georgia, who believed the original stock came from an English settlement at Savannah in Georgia in 1733. He bred huge, powerful but active dogs weighing over 100lbs. He started his kennel in the early 1950s, buying the best dogs he could from 'bulldog country' like Calhoun, Georgia, Big Sand Mountain in Alabama and Lookout Mountain in Tennessee.

John Blackwell of Collinsville, Oklahoma, one-time President of The American Bulldog Club of America, informed me that the breed is free from the physical and mental weaknesses of so many purebred dogs registered with the American Kennel club and require no training as guard-dogs. The breed comes in a variety of colours, but white or mostly white is the most common. Brindle and fawn dogs are not uncommon but usually feature plenty of white. Dogs can range in weight from 85 to 135lbs, bitches from 70 to around 100lbs. The smaller specimens, favoured by breeders such as Alan Scott, have a distinct American Pit Bull Terrier look to them, which is hardly surprising for their blood was used in the creation of the latter breed. Bill Hines of Harlingen, Texas, used his American Bulldogs as hog-dogs, in the classic medieval catch-dog manner, with all his stock being from old working lines. In early May 1999, I judged a class of American Bulldogs in an attempt to contribute to their better breeding and more established future in Britain and found them well-constructed and just as important well-tempered.

The Alapaha Bulldogs are allegedly from plantation dogs of the river region of that name in South Georgia. Around two feet at the withers and weighing just under 90lbs, they are commendably prized for their athleticism and agility. A much-respected American breeder dedicated to 'real Bulldogs' is David Leavitt, with his Olde Englishe Bulldogges. Having failed to produce what he desired from a blend of Bullmastiff, American Pit Bull Terrier and English Bulldog, he tried a different combination. He found an AKC-registered purebred English Bulldog weighing 95lbs in Massachusetts and mated this dog with one of Johnson's American Bulldog bitches to produce the type he was seeking. Since then he has certainly bred some healthy handsome Bulldogs. Jessica Izzard has imported two from Holland in the pursuit of a healthier more historically correct Bulldog.

In Canada, John and Lolly Wilkinson of Victoria, British Columbia, have their Original English Bulldogges, fit, healthy dogs which live a lot longer than the KC-recognised type, weigh between 50 and 75lbs and stand between 17 and 19 inches at the shoulder. Unlike the show ring dogs they have muzzles! They are remarkable in their resemblance to early 19th century bulldogs in England, but because they lack the exaggeration of the type favoured in today's show rings, they are rather strangely scorned by fanciers claiming to love Bulldogs yet breeding less healthy and less traditional animals.

Two other mastiff breeds from the Americas have recently been saved from extinction: the Perro Cimarron of Uruguay and the Gran Mastino de Borinquen of Puerto Rico. The Cuban Mastiff or Bloodhound, depicted in many Victorian dog books, is no more but the first two named are being restored. I would not be surprised if other Central and South American countries found mastifflike dogs in remote areas. The Portuguese and Spanish colonists took their Filas and Perros de Presa to these countries when first arriving. Staging posts on such voyages of discovery, such as the Azores and the Canaries, still have their equivalents: the Cao de Fila de Sao Miguel and the Perro de Presa Canario respectively.

The Gran Mastino de Borinquen, also known as the Puerto Rican Sporting Mastiff, is being promoted by a devoted band of enthusiasts, headed by Professor Hector De La Cruz Romero. Sometimes standing 28" at the withers, these dogs were used as boarhounds, cattle dogs and farm guards and are now progressing as a breed with its own identity. Similarly, in Uruguay, the Perro Cimarron, also known as the Perro Criollo or Perro Gaucho, and now their national breed, has been saved. Two feet at the withers, and also used as a boarhound and cattle dog, Cimarrones are strapping, athletic, well-muscled dogs, determined when working but devoted to their own family. FCI recognition is already being sought for this resuscitated breed.

At a time when many of our Bullmastiffs are being bred with truncated pug-faced muzzles, their sister breeds from the Americas have strict precautions in their breed standards to prevent such an unwise feature appearing. Some breeders seem unaware of the fact that the shape of the dog's head influences other aspects too. There are dangers accompanying too short a muzzle. First of all, the incidence of cleft palate can be increased, especially with too deep a 'stop'. Secondly, the production of extra incisors is likely. Some breeders actually favour this as it gives a wider jaw. But the presence of extra incisors is usually associated with bone disorders, especially in the forelimbs. Thirdly, the foreshortened muzzle is itself linked with a special endocrine or glandular mechanism which influences temperament, eye placement and eye shape. Change the traditional head of a breed and you change other features too.

The mastiff breeds of Europe are rarely bred as heavy hounds these days, but those of the Americas usually still are. The end of boar-hunting may have removed the need for mastiffs in the hunting field in most of Europe, but if we are to keep faith with their heritage, we should breed each and every mastiff breed as an active, athletic, physically-powerful heavy hound and not breed for bulk at the expense of soundness. In these days of moral vanity we may not approve of the use man once put such dogs to, but to condemn the dogs to an unhealthy future as cumbersome unathletic lumbering yard-dogs, with draught dog bone and a mountain dog phenotype, is a betrayal. We have misused the mastiff breeds perhaps more than any other group; it's time we made amends.