270 IMPROVING THE MASTIFF BREEDS

IMPROVING THE MASTIFF BREEDS: Honouring the Classic Phenotype

by David Hancock

State of the Breeds

State of the Breeds

Before any pedigree breed can be improved using registered stock, it is most important to assess that breeding source if past faults are to be eliminated or reduced and current faults recognised and rectified in breeding plans. Sadly, breed club shows tend to be more social gathering than serious examination of the state of the breed. Even sadder is the fact that the content of far too many post-show critiques reveal a lack of familiarity with the breed's historic function, and the design required to fulfil a role, a rather sycophantic desire to please the exhibitors, with entries falling, and a selfish, highly regrettable eye on future judging appointments. But judges at Championship Shows, often all-rounders rather than breed-specialists, can be more forthcoming and therefore give more value. In the last four years, the mastiff breeds in Britain's show rings have not impressed - with 'built-in' faults being perpetuated and serious ones being seen in exhibits subsequently bred from. This is not good news for any breed's future; here are some extracts from show judges' critiques in recent years: Mastiff: "I was very disappointed with the quantity of exhibits at Builth Wells and with some exceptions, the quality...In the UK, the Mastiffs that have been picked out and placed from the Working Group can be counted on the fingers of one hand." (Championship Show, 2011). "By far the most common faults were lack of rear angulation and weakness in hindquarters, with inadequate muscular development in second thighs." (Another Championship Show in 2011). In my lifetime, I do not recall seeing a show Mastiff with impressive hind movement.

Built-in Flaws

A third Championship Show judge in 2011, reported: "Haw is an ever-present problem...Some of the haw was slight and I did not fault that as the eyes in such cases were still quite tight...Haw is quite a persistent fault...I fear that haw, like untypical coats, is a hand-me-down from our distant St Bernard root." Have Mastiff breeders not got the skill to breed out such an inherited defect? Two years after those comments, another Championship Show judge, in 2013, reported: "There were some eyes showing haw which spoils the expression." It also handicaps the dog's vision and comfort, allowing all sorts of debris to collect in the loose eyelids. At unsanctioned dog shows I see crossbred Mastiffs with tight eyes and strong rear ends; their artisan breeders have achieved more in a short time than purebred Mastiff breeders in a century and a half! The Welsh Mastiffs of Gareth Williams in Wales display the classic, timeless, eminently sound heads of dogs bred free of breed-bias. The irrational protection of a gene pool on outdated beliefs harms dogs; type in any breed is precious but soundness must always be any breeder's first priority. You can breed for type just as effectively from sound stock as you can perpetuate traditional flaws by re-using defective genes again and again.

Concentrated Faults

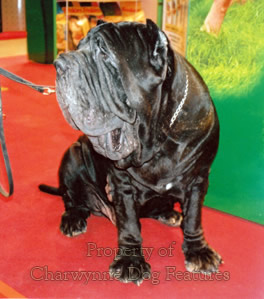

Just as there are built-in faults in our largest mastiff, our smallest one too has a comparable problem. The obsession of breeders of purebred Bulldogs with the head of their dogs has brought a wide variety of handicaps and discomfort to the breed. The jaw construction in many show ring Bulldogs is basically unsound. It was therefore good to read a critique from the judge at the Bulldog Club Inc's 2013 Championship Show that stated, very frankly: "Mouths still need to be addressed with quite a number of wry jaws, and worse still, narrow wry jaws..." Again if you look at the Sussex and Dorset Bulldogs at unsanctioned shows, you see strong sound jaws on the dogs - it can be done! I see wry jaws in Bullmastiffs too, especially in those looking too Bulldoggy in the head, never in the plainer-headed specimens. All three of these British mastiff breeds look untypical and quite ugly when they display too much wrinkling on the face, a common fault in the Dogue de Bordeaux and an over-exaggeration in the Neopolitan Mastiff. It appears that some Italian breeders actually prize the repeated folds of skin that give so much discomfort to their dogs, especially in hot weather when the deeper folds harbour all kinds of skin irritants. Accentuating breed differences to suit individual breeders is a matter for all kennel clubs to watch carefully.

Loss of Function

Our native mastiff breeds are testament to the fact that once a breed loses its function it is prey to every misbegotten human whim imaginable. Sadly the public assumes that breed fanciers know their breed and accept immobile Mastiffs, waddling Bulldogs and increasingly short-faced wrinkled Bullmastiffs as desirable perpetuations of treasured historically-correct breed type. Regrettably, the dog papers tell us far too little in depth about dogs, preferring trivia in so many breed notes to the discussion of important breed issues. There is rarely, in the world of the pure-bred dog, any serious sustained discussion about type, true type that is, just the endless round of shows, many featuring untypical dogs, which win! A debate is needed before true type in so many breeds is lost. The American breeder and vet, Leon Whitney made a key point in his 'How To Breed Dogs' of 1947, (Orange Judd, New York): "The point I am trying to drive home is this: Why should the proper type not be that which is best for the purposes for which the breed is intended?...But somebody set up a hue and cry for 'great bone' in almost all breeds and so, thoughtlessly, the bloodhound breeders who were interested in shows, had to breed for heavy ankles. Now actually there is no study which shows that heavy club-like ankles are stronger than trim ankles."

No Respect for Prototype

There are plenty of good quality Bullmastiffs in our show rings, but that quality is undermined when dogs that breach the breed standard are not only placed but extensively bred from. When a dog with excessive wrinkle becomes a champion the validity of breed assessment through the show ring is undermined. The breed standard states that even 'fair wrinkle' is not permitted when the face is in repose. By what right do judges ignore the stipulations of the breed standard? On jaw length, the standard states that the distance from tip of nose to stop must be approximately one third of the length from tip of nose to the centre of the occiput, or the crest of the skull. By overlooking this wise wording, breeders and judges are producing, not a traditional British breed, but a fawn American Bulldog. Did the pioneer breeders of Farcroft, Pridzor, Wynyard and Bulmas dogs ever intend this to be the destiny for the breed they handed down to us? Do the Bullmastiff breeders of today truly know the breed? Do they respect its prototype?

The same question could be put to Mastiff and Bulldog breeders with even greater justification. The sheer perversity of many breeders in these two breeds is astonishing, in the light of sustained criticism, often from within the breeds, over two centuries. Writing on the Mastiff in 1891, the American expert William Wade, commenting on the tendency to judge the breed solely on its head, wrote: "...you will probably get waddling, ugly brutes that will never rise above the position of prizewinners under 'fancy' judges." The man was a prophet! Six years later the much-respected Dalziel was writing: "...when the present rage for heads of immense girth, and exaggerated truncated muzzles in Mastiffs subsides...the extravagantly massive and unwieldy frame that is so popular...give us once more a Mastiff that can gallop and take a fence..."

Informed Comment

Twenty years ago, the highly regarded show ring judge Liz Cartledge was writing in a Mastiff critique: "I also had problems with lameness, such heavy animals landing awkwardly just getting out of a car can often make them unsound for weeks." Is it moral to breed dogs to such a weight? One Belgian fancier has stated that he doesn't come to English shows any more because our Mastiffs are so bad. Do our Mastiff breeders truly know the breed? A move away from traditional type also occurred in the Bulldog. Earlier, I referred to the writing of James Watson in his The Dog Book of 1906; he recalled visiting an Alexandra Palace dog show in the late 1870s and being briefed by the Bulldog breeder Bill George's son, Alfred. He was told by Alfred that '...there has been a great change since you went away. You will see some of the old sort at father's, but they don't do for showing.'

That last phrase is the killer: don't breed for type, don't breed to honour tradition, breed to win in the show ring. This kind of narrow, selfish, visionless, harmful, disrespectful thinking has threatened the future of more than one breed. Show ring whim brings no consistency, no guarantee of soundness, no motivation for improving a breed. It is driven by wallet-conscious exhibitors, not by those who truly know the breed. The Bulldog expert Edgar Farman, writing in 1899, gave this view: "From one extreme breeders have gone to the other, and the national dog in many instances is not possessed of those characteristics of which he always figures as the emblem. Excellent as an example of distorting nature by patient inbreeding...he is a manufactured article - a mass of show points." What a sad commentary on the fanciers of the Bulldog. Dog shows were never intended to provide an arena for the parading of breeds exhibiting a 'mass of show points'. They were intended to provide a contest between good dogs, so that breeding material could be identified. Some breeds have benefited from such an honourable intention, some have not. The famed Englische Dogge or English 'docga' and the English 'bulldogge' do deserve immense respect; neither was an inactive yard-dog. Both were remarkable canine athletes and shame on us for not respecting that legacy. The phrase ‘a mass of show points’ indicates the work of the faddists and their priorities.

The Harm done by Fads

Fads may be passing indulgences for fanciers but they so often do lasting harm to breeds. If they did harm to the breeders who inflict them, rather than to the wretched dogs that suffer them, fads would be more tolerable and certainly more short-lived. But what are the comments of veterinary surgeons who have to treat the ill-effects of misguided fads? In his informative book The Dog: Structure and Movement", published in 1970, R.H.Smythe, a vet and exhibitor, wrote: "...many of the people who keep, breed and exhibit dogs, have little knowledge of their basic anatomy or of the structural features underlying the physical formation insisted upon in the standards laid down for any particular breed. Nor do many of them -- and this includes some of the accepted judges -- know, when they handle a dog in or outside the show ring, the nature of the structures which give rise to the varying contours of the body, or why certain types of conformation are desirable and others harmful."

Against that background, it is worth studying the words of Mastiff specialist judge Nick Waters on judging an entry of 57 Mastiffs from 8 different countries at the 2000 show of the Belgian Mastiff Club: "What did concern me the most were the hindquarters and movement. Straight stifles, narrow, lacking muscle and some were unsound fore and aft, and far too many were close behind, lacking strength and drive, and the front legs were doing all sorts of things - rather than propelling the dog, the hindquarters just followed on." If you compare his words with those of the Mastiff judge at the 2006 Crufts; "In some classes, when the dogs were lined up to give me a good view of the side profile, less than half displayed the proportionate body length...a few were so short that I noted them as more resembling a Mastiff head on a Bullmastiff body." Did these exhibitors truly know their breed? Are they well enough informed to be proudly displaying such dogs?

Having watched the judging at Crufts over the last decade on Working Group Day, I can see why such words were forthcoming. Having gone to my first dog show just about fifty years ago, I feel, with enormous concern, that things are getting worse rather than better. In his book, Smythe goes on to say that "...the same may sometimes be written regarding those whose duty it is to formulate standards designed to preserve the usefulness or encourage the welfare of the recognised breeds." Encouraging the welfare of the recognised breeds has to be the underlying mission of not just the Kennel Club, whom Smythe is pointedly criticising, but every breeder, every breed club and every judge officiating at dog shows.

Importance of Condition

Spending a day at the Working and Pastoral Group's Day at Championship Shows in recent years has given me enormous food for thought; sometimes I've been quite shocked - by the physical condition of far too many of the exhibits. Are these not the shows of the year for those breeds that were meant to work? I use the word 'shocked' quite legitimately because, if the breeders, the exhibitors and especially the judges are prepared to go along with this situation, there is something fundamentally wrong - with worrying possibilities for the future. Of those who argue that such a show is just a beauty contest and the condition of the dogs an afterthought, let me ask a couple of questions. Firstly, when did you ever see a national beauty queen with a spare tyre and podgy limbs? Secondly, what is the point of having a serious hobby if you don't take it seriously, especially if you want to win? And thirdly if exhibits are expected to be in "show condition", why are judges taking a different view? I was also disturbed to watch four successive classes of one breed being 'judged', without the exhibits' feet once being examined. The bite of each dog was checked and infinite care taken over the comparative assessment of the entry. But feet are crucial to working breeds, as stressed earlier, more important even than mouths. Why does the organisation inviting the judge invite such an inadequate individual?

In 2013, in keeping with the KC's introduction of veterinary inspections at shows before some named 'high profile' breeds can proceed from Best-of-Breed placings to Best-in-Show judging, a Mastiff and a Bulldog both failed the test at The Midland Counties Championship Show. Based on the KC's wish for such a health check to be 'a visual veterinary observation and opinion on the findings, at the time of the examination, to establish whether the dog's health and welfare is compromised, rendering it incapable of competing in the Group competition on the day.' This examination was intended to be an objective assessment checking on signs of pain or discomfort resulting from exaggerated conformation, such as excessive wrinkling on the dog's face. The Mastiff had a rash under her chin; the Bulldog had a mark on his eye caused by an old injury. But, veterinary inspection apart, were these two dogs in show condition or is that no longer a consideration.

Importance of Definition

But what is actually meant by the expression 'show condition'? The Kennel Club's Glossary of Terms definescondition as: "Health as shown by the body, coat, general appearance and deportment. Denoting overall fitness." Not brilliantly written but the last phrase is the key one. Frank Jackson, in his most useful "Dictionary of Canine Terms", defines condition as: "Quality of health evident in coat, muscle, vitality and general demeanour." Harold Spira, in his "Canine Terminology", describes it as: "An animal's state of fitness or health as reflected by external appearance and behaviour. For example, muscular development..." The Breed Standards and Stud Book Sub-Committee at the KC inform me that show condition indicated an expectation of "a dog in good health as indicated by good coat condition, good muscle tone, a bright eye and up on the feet", adding that any competent judge would know this. One thing is inescapable in the interpretation of these definitions, condition means fitness as demonstrated in the dog's muscular state. Why then, at the Working Group shows each year, are judges putting up flawed dogs, so often in poor muscular condition and quite clearly not fit? Is it ignorance, incompetence or indifference? Some of the judges I watched simply did not know soft muscle from hard and seemed incapable of detecting the absence of muscular development. I shudder to think where this will lead us! Judging livestock is essentially a subjective skill based on what you see in the entry not what the exhibitor wants you to see. Rather than a reaction to the animal before you, it is more a conscious action to relate the animal presented to you in the ring to the beau-ideal for that particular breed. Dogs with dirty teeth and coats, skin conditions, poor muscle state and exaggerated physiques should not even be judged!

Unworthy Tickets

It is tiresome to see yet another Bullmastiff get its breed ticket at Crufts demonstrating extremely poor hind movement. (It is even sadder to see the Best-in-Show there clearly afflicted by a luxating patella in its right hind leg!) If this is "the best of the very best" as the Crufts slogan once assured us, God help the mongrels of England! There would be enormous merit in dogs at KC-licensed shows being judged on movement alone for a few years, especially in the so-called 'head' or 'coat' breeds; at least it would result in the winning dogs being able to walk properly! The relentless pursuit of a muzzle-less Bulldog by contemporary breeders leads to distress in the dog. The vomer bone in this breed may be incomplete or more deeply notched at its front end than is desirable and this interferes with the suspension of the soft palate, giving rise to difficulty in breathing, especially in hot temperatures. This condition is often compounded by faulty development of the sphenoid bone, increasing the discomfort to the dog. At the World Dog Show in Brussels I saw a Bulldog collapse in the ring on a really hot day, be carried out of the ring by its handler, wrapped in cold wet towels for a while and then brought back into the ring, only to collapse again. Does such a person really love Bulldogs?

The jaws of so many breeds have fallen victim to thoughtless show points or perhaps breed points not thought through. Breeds ranging from the Poodle to the Chihuahua now have too narrow a jaw, too narrow that is to find space for the correct number of teeth. Conversely, broad-mouthed breeds like the Bulldog and the Boxer frequently display too many incisor teeth in both lower and upper jaw, as nature fills the unnatural width of mouth. Outward appearance impresses the judge but a faulty mouth does the possessor no good at all. Internal soundness is mainly a moral issue for breeders but it also needs special attention from the more perceptive judges.

Stretched Hindquarters

We can stretch the jaw in width and length and the dog can still live a reasonably happy life. But when we seek to 'stretch' the hindquarters the consequences are much more worrying. We are then affecting the dog's ability to move as well as the best interests of its bone structure. Inequality between the length of the rear stride and the length of the front stride is producing ugly unsound movement in an ever increasing number of breeds as the contemporary fad for hyper-angulation in the hindquarters gathers more and more momentum. In the Dachshund the hind feet have difficulty keeping tally with the front ones. This, combined with inflexibility in the spine, produces a failure of synchronisation behind. In soundly constructed dogs sufficient angulation in the hindquarters and adequate length in the tibia enables the hock to flex and the hind foot to advance beneath the body enough so that balance is maintained. The side effects of excessive angulation in the hindquarters of a number of pedigree breeds are increasingly manifesting themselves. Why then is it becoming almost 'de rigueur' in breeds like the Boxer, the Dobermann, the show Greyhound, the Great Dane and the show Whippet?

In every animal walking on four legs the force derived from pressing the hind foot into the ground has to be transmitted to the pelvis at the acetabulum, and onwards to the spine by way of the sacrum. In over-angulated dogs the locomotive power is directed to an inappropriate part of the acetabulum. In addition, so as to retain the required degree of rigidity of the joint between the tibia and the femur, other muscles have to come into use. In the over-angulated hind limb, the tibia meets the bottom end of the femur at such an angle that direct drive cannot ensue. The femur can only transmit the drive to the acetabulum after the rectus femoris muscle has contracted, enabling the femur to assume a degree of joint rigidity when connecting with the tibia. This means that the femur rotates anticlockwise whereas nature intended it to move clockwise.

Excessive angulation in the hindquarters, with an elongated tibia, may, to some, give a more pleasing outline to the exhibit when 'stacked' in the ring. But, in the long term, it can only lead to anatomical and locomotive disaster. Such angulation destroys the ability of the dog's forelimbs and hindlimbs to cooperate in harmony in propelling the body. Yet I have heard it argued by breed specialists at seminars that it will increase the power of propulsion operating through the hindlimbs and on through the spine. If it did, the racing Greyhound fraternity would have pursued it with great vigour. I have heard a dog show judge praise an over-angulated dog because it 'stood over a lot of ground'! So does a 'stretched limousine' but it requires a purpose-built construction to permit the luxury.

The Importance of Shoulders

For me, the first point of real quality in a dog lies in clean sloping shoulders. Well-placed shoulders give a perfect base for a proud head carriage. They provide too the balance between the length of the neck and the length of the back, preventing those disagreeable dips in topline which mar the whole appearance of a dog. I learned, over the years, to start any judgement of the shoulders by considering the position of the elbow. If the elbow is too far forward, then the dog is pulling itself along, not pushing itself along, capitalising on the drive from the hocks and thighs, through the loins. The great Foxhound expert, Capt Ronnie Wallace, in his video on the packhounds, states that the shoulders are controlled by the elbow. He knows his stuff; he bred superbly constructed hounds. In the editorial of The Kennel Gazette of June 1890, the writer states: “If we take such an essential matter as shoulders, and ask an old bulldog breeder, he will say that while heads have improved the dogs of the present have in many cases lost the good shoulders of the old dogs…” Without well-placed shoulders the dog’s whole activity is handicapped.

It is only when the scapula and the humerus are of the right length and correctly placed that a dog can achieve the desired length of stride and freedom in his front action. Sighthounds can have their upper arms 20% longer than their scapulae. In smaller breeds they tend to be equal in length. Dogs that step short in front are nearly always handicapped by upright shoulders and short steep upper arms. A dog of quality must have sloping shoulders and compatible upper arms to produce a good length of neck, a firm topline without dips, the right length of back and free movement on the forehand. The upper arm determines, with its length, the placement of the elbow on the chest wall. Many dogs that are loose at elbow are tight at the shoulder joint and the forelegs tend to be thrown sideways in a circular movement. If the dog is tight at elbow the whole leg inclines outwards, causing the dog to 'paddle'.

When judging 'galloping breeds' I always check the space between their shoulder blades at the withers. Much indifferent movement stems from a faulty forehand construction. The placement of the shoulder blades and the elbows being the source of the problem. The shoulder blades of a working breed are vitally important. They have to support weight, they absorb concussion from the gait, they work hard when the dog is changing direction, they permit free movement of the head. Loose elbows are often accompanied by other front leg faults: slack pasterns, splayed feet or feet that turn in or out. Dogs with correctly sloping shoulders and compatible upper arms rarely have such a problem. When shoulders are correctly sloped, the topline runs through much more smoothly, giving a far cleaner look. The shortening of the neck from the forward placement of the shoulders does seriously impede a working dog. No working dog deserves incompetent breeding bestowing handicapping features on it. When moving, 60 to 70% of a dog's weight is distributed on the front legs; the forequarter construction decides the soundness of the dog's movement.

I once actually heard a speaker at a breed seminar argue that a short neck, upright shoulders and short upper arms made an exhibit look more impressive when stacked in the show ring. It allegedly made the dog stand right up on its toes and lift its head at a higher plane, so that it looked 'more statuesque'! I don't think I have ever heard a greater insult to show judges. If we are going to breed physically-crippled dogs to please mentally-crippled judges, then the sport of showing dogs is drawing to a close. But we do need judges who can assess forehand construction wisely. Working dogs need informed assessment; winning dogs get bred from. No dog with an unsound front assembly should ever be bred from.

Incorrect Placement

I have long understood that long-arched necks give flexibility to the head carriage and usually go along with good shoulder placement, the two combining to give the dog an air of quality and style. This is exemplified in top quality Great Danes. Long cervical bones, long dorsal bones, a 'bump in the front', adequate upper arm length and a gap between the scapulae at the withers are not difficult to detect when viewing and 'going over' an exhibit. Two Bullmastiff judges' critiques in recent years on this aspect make sobering reading: Manchester, 2000; 'A worrying aspect was the number with incorrect shoulder placement, too many were far too upright, which not only unbalanced them in front, it also affected their overall action. This needs watching.' Crufts, 2004; 'Too many were upright in shoulder with short, steep upper arms, restricting movement so that there was virtually no forward extension...' For a powerful breed, sound construction is vital; for good movement, sound construction is essential.

In his book The Conformation of the Dog, RH Smythe wrote: "One reason why a sloping shoulder is preferable lies in the much freer and faster action which is associated with this type of conformation...A good shoulder is much more likely to be accompanied by a good length of chest and by additional lung space than one which is badly spaced." A famous Newmarket trainer used to stress 'No shoulder, no horse!' A famous professional huntsman advised 'Necks and shoulders! get the necks and shoulders and the rest will come!' These are the cries needed for soundly-built dogs; we select the breeding stock, so we shoulder the blame. If you want your Bullmastiff to move like an Airedale, ignore the crucial importance of shoulder placement. If you want your Bullmastiff to move like a Foxhound, give shoulders top priority. You might even, under an enlightened judge, win a prize for a sound dog; but more important still, you will be respecting your own working breed.

In the Bullmastiff breed standard, the shoulders are expected to be 'muscular, sloping and powerful, not overloaded'. This, for me, is far too brief and open to false interpretation. In his informative book The Saga of the Dogue de Bordeaux of 2007, Raymond Triquet writes on shoulders for that breed: "A wrestler's shoulders. The muscles are prominent. The shoulder blade is set at the normal angle of around 45 degrees to the horizontal...this oblique lay and the mobility of the shoulder allow the D de B to take those long strides mentioned in the paragraph on gait...The angle of the shoulder blade with the upper arm is said to be somewhat more than 90 degrees. It's very difficult to measure, but it will be about 100 degrees (normal in a short-lined or compactly-built dog). In any case, it's clearly seen in profile: the upright front leg stands back a little, underneath the body."

Upright shoulders are becoming acceptable in many breeds; judges don't seek that 'upright front leg standing back a little, underneath the body', which Raymond Triquet stresses. In most show terriers there is no 'bump in the front', just a smooth uninterrupted line from throat to toes. Thirty years ago many of the Oldwell and Bunsoro Bullmastiffs had beautiful shoulders and the judges rewarded them. When they moved they drove themselves over the ground; when the front leg is too far forward, the dog pulls itself along, a very tiring exercise. A good judge should be able to spot whether the elbow is back and under the body, to detect a lack of forward extension and a front action that pulls rather than pushes on the ground.

The Importance of the Loin

What is the loin? The KC definition describes it as the "Region of the body on either side of vertebral column between the last ribs and hindquarters". From that brief imprecise description, it is easy and forgiveable to understate the importance of this part of the canine anatomy. Nearly every breed standard dismisses the loin in a few words; it is rare to read even a mention of the loin in judges's critiques of their show entry. This might be understandable in say a Toy breed, but is a disappointing oversight in hound, terrier or gundog breeds. When I watch judges going over exhibits at shows I am amazed at how little attention is paid to this desperately important part of the canine anatomy. In a powerful dog, the loin provides transmitted strength between the quarters.

In the Bullmastiff's standard the loin is considered to be part of the hindquarters, as does that for the Dogue de Bordeaux and the Neapolitan Mastiff. The Newfoundland's standard regards the loin as part of both the body and the hindquarters. Is anybody overseeing or coordinating these vital word pictures of a breed? The loin has the same function and location in every breed. Judges of each breed need to be aware of the loin. Good length of loin can make a dog look more rectangular than square, when the actual distance from the sternum to the point of buttock is in reality not much greater than the height at the withers. A short-loined exhibit can so often be more eye-catching, especially if it displays a long neck and upright shoulders, but it is not a sound animal.

The long dorsal muscle, which extends the spine or bends it to one side, is especially noticeable in the loins, where each vertebral bone carries the weight of the body in front of it, together with the weight of its own body mass. Towards the sacrum, each vertebra is accepting greater total weight than the one before it - the vertebrae enlarge, moving rearwards, throughout the lumbar region. It is not difficult to appreciate therefore the importance to the huge heavy dog, as well as the fast lithe leaping dog, of the loin. Breeders of Foxhounds have long been aware of this importance.

Knowledge of how a dog's anatomy works, rather than mystical powers, is why the so-called gift of 'an eye for a dog' puts one judge in a different class from another. A desirable arched loin can be confused with a roach or sway back. An exhibit may get away with a sagging loin in the show ring or even on the flags at a hound show; but it would never do so as a working or sporting dog. It would lack endurance and would suffer in old age. Yet it is, for me, comparatively rare to witness a judge in any ring in any breed test the scope, muscularity and hardness of the loin through a hands-on examination. For such a vital part of the dog's anatomy to go unjudged is a travesty. The lumbar vertebrae are quite literally the backbones of the loins, lumbus being Latin for loin. Any arch should be over the lumbar vertebrae and not further forward. It is vital that show breeders, who really keep the breeds alive, keep in mind always the role that gave us the breeds of mastiff we value today.