263 THE SIGHTHOUND CULTURE

THE SIGHTHOUND CULTURE

by David Hancock

Moving at Speed

Moving at Speed

“…in estimating the Greyhound’s claim to be the handsomest of the canine race we must remember for what his various excellencies, resulting in a whole which is so strikingly elegant, are designed. Speed is the first and greatest quality a dog of this breed can possess; to make a perfect dog there are other attributes he must not be deficient in; but wanting in pace, he can never hope to excel.”

Hugh Dalziel, writing in his The Greyhound, Upcott Gill, 1887.

“All sighthounds are ‘high drive’ dogs, being stimulated to chase by moving objects. I’ve seen young coursing dogs, out for the first time on the flat fens of East Anglia, take off after a car speeding along a distant by-road, maybe a quarter-of-a-mile away. They have been stimulated purely by the moving object with no thought as to what it might be. The drive in sighthounds, particularly the coursing Saluki-type lurchers, has been so enhanced that it overrides just about every other trait.”

Lurcher expert Penny Taylor, writing in The Countryman’s Weekly, 7 Sept, 2011.

Using Their Speed

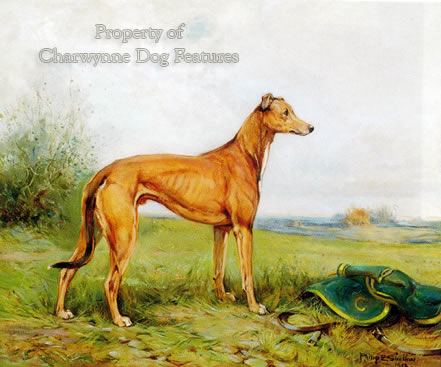

The hounds that hunt using their speed would have been better named the cursorial canines or better still, ‘coursers’, but have become known as sighthounds. The German word for sighthound is ‘windhund’ and their expression ‘von Wind haben’ means to get wind of; in some ways that is better, for whether by sight or scent, all sporting dogs become aware of their quarry by getting wind of it. Hunting by speed depends on the pace of the dog and its willingness to speed after a fast-moving quarry. Sighthounds without hard muscle and an alert eye are a sad sight, to me they have simply lost the right to be regarded as sighthounds. To develop a type of dog to excel at a particular function, with a specially designed physique to do so, and then let it waste away is a betrayal. To deny it the chance to run fast is a form of indirect cruelty; that is what it’s for! It’s therefore cheering to hear not just of Greyhound Racing but of Whippet and Lurcher racing, and of Afghan Hound racing being conducted too. Dogs bred to race need to exercise their sheer muscular power.

Astonishing Power

The Whippet for its size, may well be the swiftest of all animals. Some years back, in a lecture at the Royal Institution on 'The Dimensions of Animals and Their Muscular Dynamics', Professor AV Hill made a number of salient points. He pointed out that a small animal conducts each of its movements quicker than a large one, with muscles having a higher intrinsic speed and being able proportionately to develop more power. The maximum speeds of the racehorse, Greyhound and Whippet are apparently in the ratio 124:110:110 but their weight relationship is in the ratio 6,000:300:100. The larger animal however can maintain its pace for longer periods. Professor Hill suggested that up a steep hill, the speed of a racehorse, Greyhound and Whippet could be in reverse order to that on the flat. It is generally held that a Whippet's best performance is over a furlong on the flat, when it can capitalise on its ability to provide the maximum oxygen supply per unit weight of muscle. This is a very efficient running dog.

Performing the Function

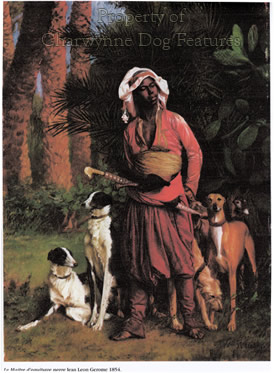

It isn't just sheer speed, agility comes into it as well. Agility matters hugely in say a wolf hunt too, for the wolf is a daunting adversary: brave, strong and athletic. Bigger quarry such as deer are naturally agile too. Stamina has to accompany speed and agility too. In the Middle East I have watched two Salukis race out of sight over ground which would have broken some dogs' legs and over a distance which would have taken the pace out of many hounds. I was not surprised when a lurcher breeder once told me that the greatest benefit from the blood of the Saluki came in the feet. The Afghan Hound also needs remarkable feet to cope with the terrain in its native country. We may not want our Afghans and Salukis to sprint over rocks or our Borzois to hunt wolves, but they came to us as breeds developed for a function and with an anatomy which allowed them to perform that function. We ignore that original function and we imperil the breed.

Show-ring Changes

We have to be extraordinarily careful that in the pursuit of show success, whether in lurcher rings or at KC-licensed events, we do not end up destroying the key elements in these handsome functional speedsters. A sighthound needs lung and heart room in abundance; it must have great forward extension, facilitated by sound shoulders. Short straight upper arms are creeping into so many sporting breeds these days and it is introducing quite untypical and most undesirable movement. The importance of sound shoulders can never be stressed enough in any hound breed. A hound built for speed, whether a Spanish Galgo, a Hungarian Agar, a Tasy or a Taigon from Mid-Asia, a Moroccan Sloughi or an Azawakh from Mali, must have the anatomical attributes that provide sprinting power. Some foreign sighthound breeds look different now from the original imports; the Afghan Hound certainly has more coat and the Borzoi can feature a markedly convex back as opposed to the more or less level topline of the early imports.

Energy and Heat Storage

Hunters and sportsmen the world over know that the ability to catch game using speed demanded a very distinctive build. The sighthounds bound; they must have the height/weight ratio, the leg length and the liver-size to sprint. Sighthounds race entirely on liver glycogen, sugar activated from the liver. Sprinting demands long legs and a sizeable liver. The bigger the liver the more sugar can be stored. A sighthound over 65lbs in weight would theoretically have more of a problem through heat storage, although their streamlined build allows the presentation of a greater surface area. We are good at getting rid of excess heat and not very good at storing it. Dogs are the reverse, removing excess heat from their surfaces rather as a radiator gives off heat.

Measuring Performance

When sighthounds were traded, such technicalities were not known but the radiator-like build, size without weight and long legs meant something to their traders. The most successful sprinters had the build to succeed and were traded and perpetuated. In breeding for appearance only we need to bear in mind those anatomical essentials that made sighthounds what they are: internationally renowned sprinters. An 85lb Borzoi will experience difficulties when running flat out; a Greyhound of any weight with a small liver will have an even bigger handicap. Traders in such hounds couldn't measure livers but they could measure performance. Some of these overseas breeds are being perpetuated here only in the show ring. The worry is that, in time, show ring criteria will shape them, not function. If you look at the Afghan Hounds first imported here and then compare them with today’s breed, you can immediately spot the heavier coat, with upright shoulders and short upper arms now featuring too.

Wrong Breeding Criteria

It is so pleasing to know that Afghan Hound (and Saluki) racing is conducted in Britain; what a release for the hounds! Less pleasing is the knowledge that the best Afghan Hound racer, Fox Ellis, which won the national individual championship a record five successive times, was never used at stud. A litter sister became a champion but for Fox Ellis not to be used at stud tells you more about breeders seeking show-winner blood ahead of proven construction than I ever could. The sighthound breeds only survived to enter the show arenas because of their ability to race. And to race in their native terrain they needed sighthound characteristics not show points aimed at impressing an ignorant judge. It is insulting to import a magnificent foreign breed and then alter it for local preferences. It is also almost certain to introduce highly undesirable anatomical flaws.

Show Critiques

In 2009, two show judges’s critiques on Afghan Hounds depressed me; one read: “The more I observe modern day judges, the more I come to the conclusion that many seem to have little conception or complete lack of understanding of ‘true type’.” The second read: “So on to the most major problems which are prevalent no matter where one looks…You either have to accept it or stand alone in an empty ring.” A 2011 judge in the same breed commented in the show critique: “Although the entry was large for these days, 91 dogs entered and few absentees, the quality could not compare to previous occasions when I had the opportunity to judge Afghan Hounds in England. From what I saw, it appears that few of the many imports used at stud over the years have really been of any great help, and there appears to be little left of the beautiful, dignified, yet quietly fierce type I remember from the early days…” What sad reading! The grooming fetishists have prevailed in this breed and this insults the painstaking work done by primitive hunters in unforgiving terrain over many centuries in their native country. Our noble infantrymen sweating away in Afghanistan in recent years would much prefer not to have to wear body armour, bulky equipment round their waists and carry packs on their backs. Afghan Hounds don’t need a similar hindrance on their bodies!

Forbidden Use

When lamenting the misguided contemptible class-warfare behind the malicious Hunting with Dogs Act, which now denies many a working class sportsman his chance to fill his family's cooking pot, it is easy to overlook the previous prohibition of coursing large and small game with sighthounds on mainland Europe: in France in 1844, in Germany in 1848 and in Holland in 1924. Before this legislation, northern Europe had a distinguished heritage of hunting with sighthounds: levriers in France, Windhunden, Windspielen or Windhetzen (literally, speed-hounds, with even a separate name for those that went for the underbelly: Zwickdarmers) in Germany and the rough and smooth-coated Friese Windhond of the Netherlands. It is relevant to keep in mind too that in 10,000BC, in a world population of 10 million, all of them were hunters. By 1500AD, in a world population of 350 million, only 1% were hunters. By 1972, in a population of 3 billion, only 0.001% were hunters. Even two thousand years ago, in many parts of the world, the success of hunting dogs was the difference between eating and starving. Hunting by speed, relying on the eyes and long legs of our sighthounds, has left us a rich heritage of canine cursorial prowess.

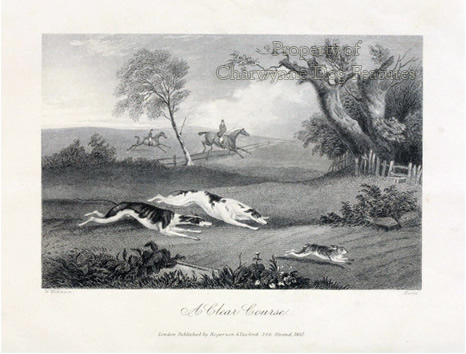

“Although hunting as Xenophon practiced it was still carried on, particularly by the Cretans and the Carians, and although the Romans hunted in much the same manner as the Greeks (as well as in great hunts of the Persian sort), a new sport was introduced into the ancient world by the Celts some time before the second century after Christ. Although it may have been called hunting, it was in fact almost exactly the same sport as what we call ‘coursing’, and its purpose was not to catch the hare but to watch the hounds race her…The hounds used were the Vertragi, a breed of greyhounds…”

Hounds and Hunting in Ancient Greece by Denison Bingham Hull, University of Chicago Press. 1964.

“Before buying a dog, always see him gallop, as freedom of movement counts for a great deal. Dogs that sprawl all over the track seldom get anywhere near the winners. Correct, symmetrical movement tending to speed and true running, can come only from dogs which are nearest to the accepted standard of perfection. It is very difficult to advise which is the most suitable size and weight. Good performances are put up by large and small dogs alike. If any special lists of sizes and weights had been kept, it is probable that dogs of between sixty and sixty-five pounds weight would be found the most suitable for both mechanical hare racing and the plumpton (i.e.coursing, DH), but no hard and fast rule can be laid down.”

The Greyhound by BA McMichan, RVS, Angus & Robertson Lyd, Sydney, 1937. He was the Official Veterinary Surgeon to The Greyhound Breeders and Trainers Association of Australia at that time.