245 Stable Companions

STABLE COMPANIONS

by David Hancock

"Men are generally more careful of the breed of their horses and dogs than of their children."

William Penn (1644-1718).

The close association between dog, man and horse is a long and varied one. All over the world, throughout recorded history, mounted hunters and sporting dogs have worked together in remarkable harmony. There always seems to have been a special affinity between dogs and horses. Neither seems to have any preoccupation with themselves, quite unlike man. Both horse and dog are more interested in external stimuli rather than self-interested introspection. This makes both of them loyal and selfless, ideal companions for each other and valuable servants to (and sometimes victims of) man.

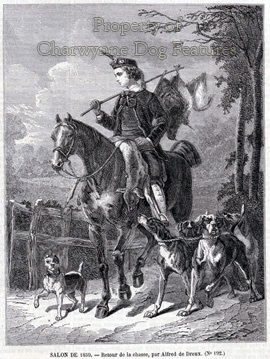

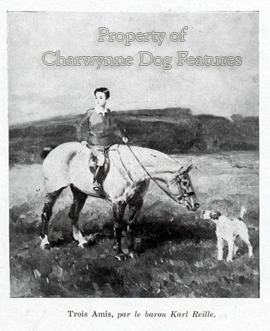

Breeds like the Dalmatian and the harlequin Great Dane have been traditionally used as coach dogs, lending a distinct elegance to coach travel, as well as having the functional value of keeping village curs from alarming the horses. Bullterriers and small mastiffs were often used to guard valuable horses in stables. Rat-catching breeds like the Manchester Terrier were widely used to keep vermin down in stables. As a direct result of such an association is the fondness for horses which many breeds of dog retain to this day. Many artists have captured this relationship very skilfully.

Down the centuries, man the hunter has needed the mobility of the horse and the catching and killing ability of the hound. Xenophon described three varieties of the Cretan hound: the Cnossians, famous as trackers; the Workers, so keen they hunted by day and night, and the Outrunners, which ran free under the huntsman's voice control only. According to Aristotle, the latter variety ran instinctively beside the horses during a hunt, never preceding them and not lagging behind. Unlike many of the other hounds used by the Greeks in the chase, the Outrunners were neither dewlapped nor flewed. They were used by the Cretans to hunt a four horned antelope, as Aelian has recorded.

These Outrunners were too valuable for use on boar hunts, where some hounds were killed. They were considered too special for use in hare hunting. Suffiently biddable to be used as 'braches' or free-running hounds, as opposed to 'lymmers' or leashed hounds, they hunted using sight and scent, rather as our own fleethounds used to. In this way, the Cretans' use of horse and hound was exceptional and showed the advanced state of their training and breeding skills. In any hunt involving hounds and horses, the latter have to show consideration for the former or injuries would be frequent.

A hunter is around 67" at the withers, a foxhound only 25"; the all-round vision of a galloping horse is not limitless yet accidents in which hooves damage hounds are almost unheard of. Just as the hound is a pack animal, so the horse is a herd animal. Each has an instinctive awareness of the other. In the hunting field, down many centuries, horse and hound have run together in mutual support and remarkable sympathy. In such an activity, horse and hound need speed, stamina, drive and spirit, with the hound also needing nose, cry, pack sense and discipline in a group. Both need sound feet; the old hunting man's expression "No hoof, no horse" has relevance for hounds too. Both need hard exercise, the right nutrition and good breeding.

In his valuable book "Hunting" of 1900 from the Haddon Hall Library, Otho Paget wrote almost a summary of such needs: "A few seconds' respite on the turnip-ground gave your horse an opportunity of getting his second wind, and he now seems as fresh as ever, but you feel very thankful that most of his forebears are recorded in the stud-book...Hounds are driving along now at a tremendous pace over the old turf, and there is not a sign of one tailing off. You are delighted with the result of your kennel management, with summer conditioning and autumn education. This is the moment when you reap the fruits of all your care and labour. In spite of the severity of the pace, neither old nor young show the slightest symptoms of flagging."

Breeders of hunters in the last century usually went for the thoroughbred horse on the half-bred mare. But some favoured the reverse, going for size and strength in the sire and quality and stamina in the dam. Some of the best hunters one hundred years ago were by half-bred stallions out of thoroughbred mares. Clearly, performance ruled with the horse then just as it did with the hound. In his "Hounds of Britain" of 1973, Jack Ivester Lloyd wrote that "...genuine hunting folk have displayed considerable elasticity of mind by introducing out-crosses when these would benefit the breed in which their interests repose. This is the reason that all hounds now hunting in Britain possess stamina, health and intelligence, virtues which could not be claimed for all the canine breeds kept as pets or for display on the show bench."

The closed gene-pool in Kennel Club-registered breeds is a classic example of the unthinking pursuit of high breeding leading in effect to low breeding. Edwin Brough, the great Bloodhound breeder, advocated an outcross in every fifth generation but his advice is never taken by contemporary Bloodhound breeders, who clearly think they know better. Such blindness persists despite the known benefit obtained from the Harrier blood in the English (hunting) Basset, from the English springer blood in the Field spaniel and from Greyhound blood in the Deerhound. Meanwhile the French value their Beagle-Harriers and prize their 'briquets', Harrier-sized hounds often cross-bred and sometimes not even entirely of hound blood.

The French long ago realised the limitations of the chien d'ordre or pure hound, as the Comte Elie de Vezins firmly sets out in his 'Les Chiens Courants Francais pour la Chasse' of 1882, calling it "slow, slack, listless and unintelligent", with a tendency to get out of breath on the hills. The Rhodesian Ridgeback and the Dogo Argentino, two magnificent breeds of hunting dog, benefit from the mixed blood of their varied ancestors. The value of sporting dog and horse has long been firmly and sensibly rooted in performance, rather than in a brief written certificate of breeding called a pedigree.

"The domestic dog", says Cuvier, "is the most complete, the most singular, and the most useful conquest that man has gained in the animal world...The swiftness, the strength, the sharp scent of the dog, have rendered him a powerful ally to man against the lower tribes; and were, perhaps, necessary for the establishment of the dominion of mankind over the whole animal creation. The dog is the only animal which has followed man over the whole earth". These comments strangely overlook the value of horse to man and ignore the remarkable contribution of horse and dog together, not just to man's hunting and sporting activities, but to exploration and farming across many centuries. Dog and horse have literally accompanied man "over the whole earth", with dog having the size advantage when it comes to sharing the hearth.

Cuvier would have been on surer ground if he had stressed the sheer versatility of dog in its usefulness to man. This versatility allied to the facility given to man by the horse and man's own unique adaptability makes an extraordinarily valuable combination. Mounted herdsmen using hard-eyed herding dogs have benefitted from this combined value for centuries, from the pusztas of Hungary to the outback of Australia. Genghis Khan used the hunting field to train his cavalry, accompanied by huge hounds. In South America, mounted huntsmen still pursue wild pig using big hounds like the Dogo Argentino. In Russia, horsemen used the handsome Borzoi to run down wolves for their ultimate sport. Whilst in the Arab world, horsemen with hawk and Salukis, continue the age-old skill of gazelle-hunting.

In each case, in each part of the world, man utilises horse and hound or herding dog to achieve his end, with all three working in harmony to one purpose. It is a unique combination in the animal kingdom and in man's use of subject creatures. Long may it continue, whatever the pressures of man's demand on land and the threat from his recently-developed moral vanity. Perhaps the complete lack of vanity in both horse and dog makes them especially attractive to man, certainly as companions. Such a mutually-beneficial stable relationship is one to be treasured and well worth preserving in times when 'townmindedness' threatens to blind our traditional affections. May 21st century man have the wisdom to appreciate and then respect such a precious partnership.