240 Setters of Style

SETTING THE STYLE

by David Hancock

"If one had to pick a dog, not a foxhound, as typical of English country life and the English country gentleman who lived it in the nineteenth century, then that dog would be the English Setter."

"If one had to pick a dog, not a foxhound, as typical of English country life and the English country gentleman who lived it in the nineteenth century, then that dog would be the English Setter."

(Sir Richard Glyn in his 'Champion Dogs of the World' 1967.)

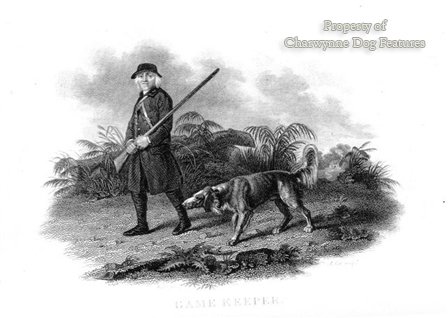

Those words straightaway provide the frame for any word picture being painted of the setters. They were the shooting companions of those with land or access to it and a life of ease, often dominated by country sports. James the First addressed the landed gentry of his time with these words: "Gentlemen, at London you are like ships at sea, which show like nothing; but in your country villages you are like ships in a river which look like great things." The passion of such men for country sports not only shaped the English countryside but gave us our hounds, gundogs and terriers. In the time of the Stewarts, the setting dog was used to hold game birds to ground, often with a hawk overhead to keep the birds from flying, while a net was carefully drawn over them. Then with the introduction of firearms and later 'shooting flying', setters were needed, along with pointers, to indicate and then put up feathered game.

In pursuit of this function, the setting dog breeds developed both here and on the continent and were widely traded, with a high value on a trained and effective dog. Whilst our setter breeds were evolving here so too were the 'epagneul' breeds on mainland Europe. It is foolish for setter breed historians to claim a long and pure lineage for their favoured breed. Good setters were mated to other good setters irrespective of colour. The landed gentry went on their Grand Tours, sometimes taking their dogs with them through Europe and sometimes coming back with a dog which had impressed them. It was easier to bring foreign dogs into Britain in every previous century than the twentieth.

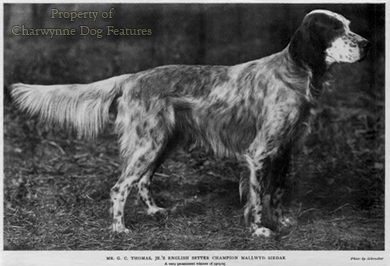

In time certain coat colours were favoured by individual sportsmen both here and abroad. The epagneul breeds varied all over mainland Europe but all had that definite setter appearance: feathering on the tail and legs, a distinct occiput and enormous style when seeking game scent. In Holland the Drentse Patrijshond and Stabyhoun emerged, in France the Epagneul Francais, in Germany the Munsterlander (and later the Langhaar and long-haired Weimaraner). In Britain, distinct strains were stabilised, often exemplified by their coat colour, with far greater variety than nowadays.

Setter colours ranged from the liver and whites of the Prouds at Featherstone Castle, keepers Laidlaw at Edmond Castle and Grisdale at Naworth Castle; the Earl of Southesk's, the Marquess of Anglesey's, at Beaudesert in Staffordshire, and Lord Lovatt's tricolours; the lemon and whites of the Earl of Seafield; Lord Ossulston's jet blacks; the milk-whites of Llanidloes and the black and tans (and tricolours) of Gordon Castle, to the black and whites of Lort of Kings Norton. In Ireland, O'Keefe and Baker of Tipperary favoured the white and reds (as the Irish called them), Capt. Butler of County Kerry went for the black and whites, whilst the reds were promoted by the Marquess of Ely, Lord Farnham, Redmond in County Dublin and the Cavendish family of County Cork.

Against that background the setter colours of today look rather impoverished; we have become transfixed by the aura of the pedigree. Not so the Duke of Gordon who was described as "not a man to confine himself to shades and fancies". He would not have approved the setters named after him needing to possess the now mandatory black and tan jacket of the breed. Not so too the founder of the modern setter, Laverack, who wrote that a change of colour was as good as a change of blood. The advent of dog shows has brought an absurd conformity, restricted breeding programmes to the dictat of the breed standard's stipulations and led to mismarked but otherwise high quality dogs being lost from the gene pool.

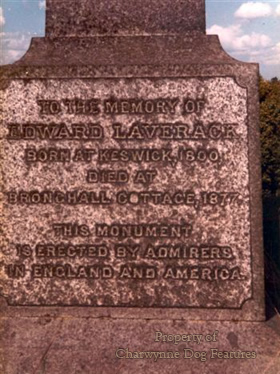

It was three non-conformists, Edward Laverack, Richard Purcell Llewellin and William Humphrey who contributed the most to the development of the working setter. Laverack's work was so admired by both American and British setter fanciers that they erected a monument to him in Ash churchyard near Whitchurch, Shropshire. Sadly, Llewellin's grave in Stapleton graveyard, also in Shropshire, is now overgrown. Fittingly for a working setter man, Humphrey's ashes were scattered over the Shropshire hills where so many of his dogs had worked and been trained. Their work, spanning well over a hundred years, ensured the quality in our setters, which we benefit from today.

Laverack (1798-1877) bought his first setters, both blue Beltons, in 1825 froma pure strain of strongly-constructed family estate dogs, carefully bred over 35 years. With an established line to perpetuate, Laverack continued this work for 52 years, giving a total of 87 years of skilful line-breeding. To him must go the credit for coordinating the best strains of setter of his time and for producing both handsome show dogs and sound workers. He is known to have used both Irish and Gordon Setter blood, with his curly-coated specimens probably having an infusion of the old Welsh Setter. Despite his age when dog shows became organised, he made up two show champions, and in the period from 1861-1892, eleven champions were 100% Laverack-bred, with only 3 out of 25 champions made up having no Laverack breeding behind them.

The first dual champion 'Countess' and her brilliant field trial winning sister 'Nellie', both bred by Laverack, formed the nucleus of what became known as the Llewellin Setter. The son of a great all-round Welsh sportsman, Llewellin established in his strain of setters the greatest field trial winning record of all breeds of pointing dogs in the 80 years from 1880-1960. His dogs were first of all a mixture of Gordon, probably Llanidloes Setter, a big milk-white curly-coated variety, and the powerfully-made Old English Setter, a black and white variety rather like the Stabyhoun, the Friesland Setter from Holland. Later he used Red and White Irish Setter bitches, eventually modifying the resulting progeny with pure Laveracks. Proud and meticulous, he never sold stock here or abroad unless he considered it near perfect. How many of today's breeders can claim that?

When you read of the blend of blood used by such inspired dog breeders as Laverack and Llewellin it makes you realise how handicapped we are by the pedigree system, paradoxically, a system designed to improve dogs. Pure breeding is fine when it's working, disastrous when it is not. But who decides, or has the moral courage to speak out when the closed gene pool in a breed is simply not good enough? Who nowadays would cross one setter breed with another? Every Gordon Setter that I see in the show ring is black and tan. One of the top recent successful working setters, a Gordon, is mainly white with black patches, owned by Bob Truman. Described as the best grouse dog this century, Laverack would have loved him and bred him with another outstanding dog -- of any colour!

When Llewellin died in 1925 he left his dogs to his housekeeper, from whom William Humphrey subsequently bought them. Humphrey saw his first field trial as a boy of nine in 1892 and won his first stakes two years later at the age of eleven. Winning his last stake in 1963, he set up the longest record of field trial successes since such trials started in 1865. He so approved the Llewellin strain that over 55 years he imported from the United States 33 dogs and bitches previously exported. His 'Wind'em' setters were so revered that when I was in Norway thirty years ago, my hosts were still recalling them. Humphrey ran a winning dog in Norway at the age of 67. He was famed for his Pointers too, at one time he ran a kennel of 1,200 dogs!

The Americans still recognise the Llewellin Setter as a separate breed. They consider that the breed comes from three lines, each bred to Laveracks. One of these lines, from 'Rhoebe', the greatest field trial winner-producing dam of all time, passes on the blood of her sire, who was the great grandson of a Gordon Setter and a dam which was half Gordon and half Southesk Setter, a strapping tricolour strain from Forfarshire. A most knowledgeable American sportsman, Joseph Graham, writing in 1904, in his informative 'The Sporting Dog', stated that: "...they (i.e. the claimants of the Llewellin as a separate breed) would as well go further and drop the 'pure' idea altogether, letting Llewellin blood stand for what it is -- an influential but not separate element in English setter breeding". In Britain we have long held that view.

Joseph Graham also states in his book that: "Purity of race is a good thing when it is good. Sometimes it is a misnamed conglomeration, and sometimes it needs breaking up and disturbance". Are we going to persevere with purity of breeds when it is "not good"? Here are some critiques in recent years on our setters in the show ring: Gordons -- "Unless something is done quickly by the top breeders, I see no hope for the breed, because the puppies were so bad." Irish Setters -- "I found quality in depth lacking, and the movement was on the whole very bad." Irish Setter dogs -- "One of my main observations is the weakening of the overall body shape, the breed is losing genuine spring of rib and becoming too slab-sided." Gordons -- "I was however rather shocked to find a lot of poor angulation front and rear, upright shoulders predominated...also too many straight stifles." English Setters -- "Poor mouths and movement were the chief faults but straight stifles and heavy shoulders were to be found."

Edward Laverack, in his book on the setter of 1872, wrote: "The first thing to be attended to in breeding is to consider what object the animal is intended for...One of the first objects to obtain, if possible, is perfection of form, as best adapted for speed, nose, and endurance. The next, and which I consider paramount, or of as much importance as physical form, is an innate disposition to hunt, and point naturally in search of game, and without which innate properties mere beauty of colour and perfection of external form (however desirable) are but secondary considerations to practical sportsmen, and simply valueless." That is a very clear statement from a master-breeder and not one to be overlooked.

Setters were designed for work, that is why they were handed down to us in the form they were. Setters which are not capable of working, physically and mentally, represent a betrayal of everything the pioneer breeders devoted their lives to. It does not matter if they are only pets; to be the genuine article they must have an anatomy which could carry out setter work. Pretty, showy, flamboyant setters floating round the ring and then earning the kind of remarks from the judge set out above are unworthy of their own heritage. And if we breed them without heeding the great founder-breeder's words, and his crystal clear message about valueless dogs, we will in time put at risk a simply splendid type of dog and an important part of our sporting dog inheritance.