226 BREEDING BETTER DOGS

SUPPORT FOR BREEDERS _-- BETTERING THE PAST

by David Hancock

The last few years have been momentous in the world of the domestic dog. The canine genome has been unravelled, the dog's DNA analysed, health clearances are increasingly available and quarantine relaxed. But if you study the records of just over a century ago, the French expression, 'deja vu', comes to mind; there is that illusory feeling of having already experienced a contemporary happening. A glance at the dog scene of 1883 provides all the material to explain that nostalgic sensation. And this was the year that Britain decided to evacuate the Sudan, the first skyscraper was built in Chicago, Brahms composed his Symphony No 3 in F and RL Stevenson wrote his classic Treasure Island. An eventful year.

The last few years have been momentous in the world of the domestic dog. The canine genome has been unravelled, the dog's DNA analysed, health clearances are increasingly available and quarantine relaxed. But if you study the records of just over a century ago, the French expression, 'deja vu', comes to mind; there is that illusory feeling of having already experienced a contemporary happening. A glance at the dog scene of 1883 provides all the material to explain that nostalgic sensation. And this was the year that Britain decided to evacuate the Sudan, the first skyscraper was built in Chicago, Brahms composed his Symphony No 3 in F and RL Stevenson wrote his classic Treasure Island. An eventful year.

In a letter to the Kennel Gazette of that year, a Gordon Setter breeder boasts that his bitch 'had eleven whelps on the 2nd of January 1883, eleven more on the 18th of July following, and that she is in whelp again, and due to pup January 25th (1884)'. Over-breeding is no new phenomenon.

In 1861, the dog show in Holborn attracted 240 dogs in 48 classes, but in 1871 the Crystal Palace show drew 834 entries to 110 classes. The biggest increases occurred in Pointers, Setters, Mastiffs and Fox Terriers. Terriers were classed as non-sporting dogs. Keepers' Night-dogs, the Bullmastiffs of today, were both recognised and shown.

The Kennel Editor of The Field, in his show reports, was, in 1883, often highly critical of judges' decisions. It would be a breath of fresh air if such a comparable second opinion were to become available today in print. It is regrettably rare for any comments to be published on judges' decisions except in letters to the editors of dog papers. Surely it is the job of any journalist worthy of the name to speak up and offer another view on judging verdicts. Why should we only receive the judge's view of his own opinion? The dog press has a duty to dogs and their improvement which, in my view, entails giving their readers another dimension on the contemporary dog scene, including critiques of judges' verdicts. The slavish often sycophantic reporting of dog shows belittles their role in identifying future breeding stock, a very serious business.

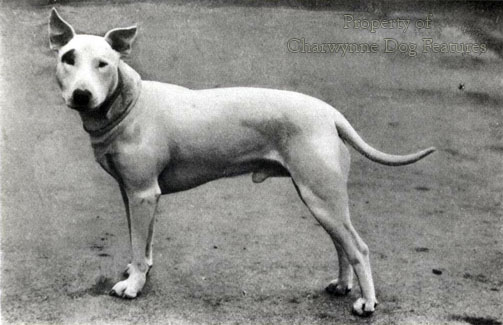

In 1883, The Old English Mastiff Club adopted 'The Points of the Mastiff', which required a massive body, a short muzzle, small eyes, heavy shoulders and very large bones in the forelegs. Such bizarre requirements still afflict this breed today. The very unappealing Mastiff Crown Prince is listed as a winner at a number of shows; it is disappointing to learn of such a poor specimen being so widely used as a sire. One Mastiff at the York Dog Show was described as having straight stifles 'so pronounced that they almost amount to a deformity'. Despite this the bearer won a prize; it is hardly surprising that straight stifles plague the breed to this day. A scathing comment on Bull Terriers at one show read that they 'were but moderate, though, according to the new ideas, no doubt, excellent specimens.' Commenting on the Bulldog Club Show, the correspondent gave the view that 'the liberality of the judge in scattering cards upon positively indifferent specimens we therefore consider ridiculous.' Real Bulldog lovers may well make the same comment on this breed at shows in 2005.

In 1883, The Old English Mastiff Club adopted 'The Points of the Mastiff', which required a massive body, a short muzzle, small eyes, heavy shoulders and very large bones in the forelegs. Such bizarre requirements still afflict this breed today. The very unappealing Mastiff Crown Prince is listed as a winner at a number of shows; it is disappointing to learn of such a poor specimen being so widely used as a sire. One Mastiff at the York Dog Show was described as having straight stifles 'so pronounced that they almost amount to a deformity'. Despite this the bearer won a prize; it is hardly surprising that straight stifles plague the breed to this day. A scathing comment on Bull Terriers at one show read that they 'were but moderate, though, according to the new ideas, no doubt, excellent specimens.' Commenting on the Bulldog Club Show, the correspondent gave the view that 'the liberality of the judge in scattering cards upon positively indifferent specimens we therefore consider ridiculous.' Real Bulldog lovers may well make the same comment on this breed at shows in 2005..jpg)

In 120 years many aspects of owning, showing and breeding dogs have changed. Some sadly have not and there is often human frailty behind such failings. What is especially disappointing is the failure of the pedigree form itself to move with the times, respond to increased knowledge and our ability to obtain and store information. If you look at a pedigree form of 2004, it could so easily be one from 1883: five generations of names of sires and dams, nothing else. Is this Kennel Club inertia, an unwillingness of breeders to expose their shortcomings, mere laziness or a fear of progress itself? There are needs not being met here, a significant omission of any indication of quality through grading and no genetic content. Both lackings do not advance the science of dog breeding or the stated desire to improve dogs. Is a healthier breed not worth pursuing?

We now have every facility for recording not just information on the phenotype of each pedigree dog, but the genotype too. But do we have the will? On mainland Europe, dogs examined at dog shows are not just placed in order of anatomical merit, they are graded too. This grading or classification relates to their assessment against the beau ideal for that breed; usually these grades are listed as Excellent, Very Good, Good, Satisfactory, Poor and Unsatisfactory. The top grade cannot be achieved until the dog is 2. A dog graded Excellent is considered to be exceptional, with no major faults, an admirable character and correct dentition. Unsatisfactory exhibits would be very poor specimens and be unlikely to be bred from---that is the major value of grading to me.

Why should we be afraid of such a scheme? Do we not accept that far too many poor quality pedigree dogs get bred from, partly because nobody is brave enough to tell their owners how poor they are? This system of judging may be slower but is speed-judging the best way to identify future breeding material? But a far more important omission on pedigree forms is any reference to the genetic health of the subject dog. In his most informative book Control of Canine Genetic Diseases (Howell Book house, 1998), George Padgett, himself a vet and professor of pathology, makes a compelling case for the inclusion of genetic information on pedigree forms. Such an inclusion could play a vital role in reducing the incidence of inherited diseases in breeds of dog. Is that not desirable?

Padgett points out the need for a registry capable of recording genetic histories in registered dogs. He is wise enough to acknowledge that breeders cannot map their dogs alone. He writes: "You do not have to be around dog breeders (purebred or otherwise) very long before you realise that the vast majority of these breeders do not have the background to allow them to draw the most accurate conclusions about the genetic makeup of a phenotypically normal dog based on a disease occuring in one of its first-degree relatives." He sets out a distinct role for registries, like our Kennel Club. He also provides the view that: "We need to forget the registries we had yesterday, because it is obvious that they did not accomplish what we thought they would. It's time to get out of the 1960s and move into the new millennium." Time too surely to get away from the pedigrees of 1883 and enhance the value of registration itself.

Padgett cites the work of a group of American breeders, in the Northwest, who reduced the prevalence of Collie Eye by 38% over a three year period. He mentions the achievement of Portuguese Water Dog breeders there who all but eliminated the breed's storage-disease problem in just a few short years. He concludes that: "It is clearly time for breeders, breed clubs, the AKC and the veterinary profession to come to grips with the problem to preserve the integrity, health and well-being of our canine friends." Again and again he stresses the key role of the registry and the need for such a body to review its role in a new millennium. Whilst we rely on the same piece of paper to certify a dog's birth and the names of its ancestors as we did in 1883, we miss a golden opportunity to advance. Such things must never remain the same, they must change.

Do we truly want to be stuck in 1883 as far as the compilation of written pedigrees is concerned? Robert Louis Stevenson wrote a classic in 1883, but he produced a classic phrase two years later, the desire 'to change what we can; to better what we can...' This should be the leitmotiv of every dog breeder and dog-registry; perpetuating the past is just not good enough for dogs. Bettering the past is the real challenge. We have the technology to better the past, all we need is the will and the vision. This is an opportunity for our dog registry, the much-criticised Kennel Club, to delight us all. And what a mission statement that would make: To establish before 2013 the issue of a written pedigree for every dog registered with us, setting out the quality of its phenotype and the health of its genotype.

The time frame should frighten no one; the information should please anyone who cares about the welfare of dogs and the integrity of breeds; the intention should impress everyone who seeks to better the lives of domestic dogs. Livestock breeders sneer at dog breeders sometimes, calling them Luddites. Breeders themselves want to enjoy a degree of freedom in their work, but surely not the freedom to breed crippled dogs. 1883 was an interesting year in dogdom; 2013 could be too.

What incentive is there for good breeders in 2005? What incentives are being offered for breeders to excel? At the moment the most prosperous breeders are the ones producing the most puppies. The Kennel Club's mandate is the improvement of dogs. How can dogs be improved if the best reward comes from over-production? One Bullmastiff kennel's stud dogs have sired over 1,000 puppies in a decade. Quantity before quality is never good for the long-term. How is type being protected from a dominant clique of breeders striving to impose their type on a breed? Who is rewarding clever working dogs in each breed? Is there any guardianship in dogdom? Good breeders producing outstanding dogs should the best rewarded. Working ability should be treasured. Breeding stock should be subject to health screening. Dogs with untrustworthy temperaments must not be bred from. Progress in these areas should ideally not come from Brussels, Westminster or Clarges Street but from breed clubs and breed councils. Those who claim to love the breed of Bullmastiff must now prove it.