187 Minor Spaniels

MINOR SPANIELS: NOT AT WORK!

by David Hancock

Spaniels were designed for work, whatever their modern misuse by man as a housedog, walking companion, hearthrug or model on the Crufts' catwalk. It was heartening therefore to once see a group of devotees of the minor spaniel breeds assemble on the Shugborough estate, near Stafford, which I managed for 14 years, for a working test organised by the admirable Field Spaniel Society. I had the pleasure of assisting Geoff Nicholls, gamekeeper and field-trial judge, on the day. The ground used offered good spaniel-testing country: bracken, bramble, long grass and fallen branches, but not too impenetrable to daunt young and inexperienced entries.

Organised by Clive Rowlands, generously sponsored by Dodson and Horrell, the day will not be remembered so much for impressive spaniel work as for the encouragement it offered to well-intentioned owners anxious to keep working instincts alive. The schedule attracted field spaniels (mostly), Clumbers, Welsh springers, Sussex and Irish water spaniels (i.e. any variety except cockers and English springers) and spanned novice, open and puppy classes.

The Kennel Club gundog working test regulations, introduced this year, state that ..."a spaniel's first task in the shooting field is to find game and flush within range of the handler...credit points - natural ability, nose, drive, marking ability, style, control, quickness in gathering retrieve, quietness in handling, retrieving and delivery." Listed faults include: "...running in and chasing...out of control." At the risk of offending many, how I wished some of these minor breed spaniels on that day had chased and run, out of control or not!

For here we had a collection of willing owners, very commendably trying to work their dogs, driving a long way on a hot day to do so, giving up their valuable time, really striving to keep the minor breed flag flying, only to find that with one or two exceptions, their spaniels would not hunt. I say "would not", perhaps "could not" is more accurate. At first I wondered about the scenting conditions on the day but then we sniffed fox, saw recent signs of deer and rabbit and I know that pheasant abound in that area of mixed woodland. Yet here were sporting dogs, whose first task is to find game in the shooting field, displaying no excitement ahead of their noses, no enthusiasm for gamefinding, no keenness to work, no interest in their breed's role in life.

Unless a spaniel, of all breeds, is excited by game scent, wants to hunt and is self-motivated, how can any trainer, skilled or novice, bring him on ? These spaniels had excellent temperament, no obvious physical impediments, no apparent distractions, no excuses. They simply would or could not hunt. Not one of them got under the bramble and "made it move" as Geoff Nicholls put it. The basic element in any working dog simply wasn't there. A number of these spaniels retrieved quite capably, walked to heel and stayed on command. But so can so many breeds, not necessarily gundog breeds.

.jpg)

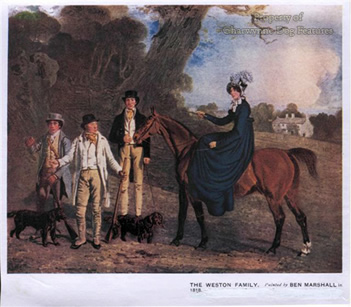

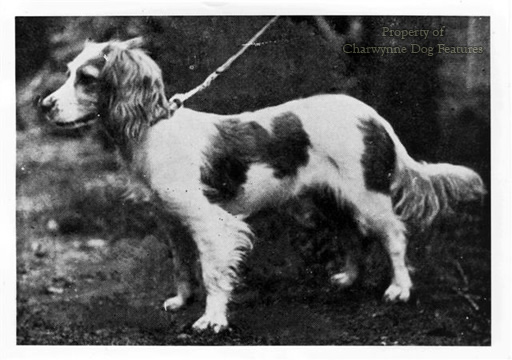

For me the biggest shock of the day was this fundamental unwillingness of these spaniels to seek game, with zeal - and tails frantically working. As a direct result of this concern, both Geoff and I in the judges' critique at the end of the test, felt compelled to propose the unthinkable (nowadays): the use of outside blood to get the hunting instinct rekindled. I was in favour of an outcross (for the fields) to a working English springer. This has happened before; pre-war 'Icy Kiss' was produced from a field bitch,'Wardleworth Libby', and an English springer dog 'Dismal Desmond' (of field trial breeding) and, post-war, Lady Lambe's 'Whaddon Chase Duke', who was bred to show champion 'Teffont Lalange'.

But Geoff Nicholls proposed inter-breeding with a liver cocker and, not surprisingly, knew just where to go for one. This raises an issue which, whilst making lurcher and working terrier enthusiasts laugh out loud, has to be faced by all sportsmen who value dogs for what they can do rather than what they look like. The question is: Are dogs valued for their pedigree or their prowess? Over the last 150 years breeding for the pedigree and showring certificates has ruined breed after breed. "Got a pedigree long as your arm" has been used ingenuously as an excuse for non-performance for far too long. Yet spaniels of all the gundog types have been interbred, outcrossed and reclassified the most.

These minor breed spaniels, owned and handled by a most likeable and admirably-intentioned bunch of devotees, could not work! Some lacked confidence; some retrieved soundly, one (a field spaniel of Clive Rowlands's breeding) might make progress if worked with a really keen young Engish springer for a while. Perhaps we should look again at how we mark spaniels at working tests, giving the highest marks for hunting ability, encouraging raw material with essential spaniel characteristics and not worry quite so much about the finer points of dummy-carrying. Not one of these spaniels went under cover; most went round it altogether.

Of course, in the gundog world, there are plenty of fine working dogs: cockers, English springers, Irish setters, pointers, labradors and, increasingly, the 'hunt, point and retrieve' breeds. But the minor breeds of spaniel are part of our national sporting heritage, with genetic importance too. Much as I admire a top-class field-trial labrador or cocker, I just as much want to see the separate idiosyncrasies of the less popular breeds conserved. A cross-bred spaniel that can really work is a much more valuable animal to me than any statuesque showring poseur with no working capability. As Wilson Stephens, doyen of contemporary gundog writers, once drily wrote: "They didn't send male models to recapture the Falklands!" Those involved in the future of our minor breeds of spaniel have much to think about.