157 Scenting Success

SCENTING SUCCESS

by David Hancock

Perhaps the greatest failing of man in his understanding of dog is his recurring inability to appreciate how dominant in the senses of the domestic dog is the sense of smell. For man the main detecting senses are sight and hearing, indeed I have read scientific papers claiming that our sixth sense only lapsed because of the high quality facility given to us by our eyes and ears. I have also read articles in country magazines extolling the superb eyesight of dogs, which I find hard to justify. I have never come across a dog with better all-round eyesight than man, although we will never be able to match their remarkable detection of movement. Never too will any of us ever match the quite astonishing sense of smell in dogs.

Perhaps the greatest failing of man in his understanding of dog is his recurring inability to appreciate how dominant in the senses of the domestic dog is the sense of smell. For man the main detecting senses are sight and hearing, indeed I have read scientific papers claiming that our sixth sense only lapsed because of the high quality facility given to us by our eyes and ears. I have also read articles in country magazines extolling the superb eyesight of dogs, which I find hard to justify. I have never come across a dog with better all-round eyesight than man, although we will never be able to match their remarkable detection of movement. Never too will any of us ever match the quite astonishing sense of smell in dogs.

One of my dog-owning neighbours was recently quite apologetic to me because she always took her dogs on the same country walk. Each time she walks that route she sees the same scenes and gets very used to the appearance of the scenery within sight. But for her dogs each of those walks is a different experience despite following the same route each day. For across that path, farm animals, wild creatures, other dogs and fresh humans have moved and every day the smells will vary. This is the stimulation which the astounding sense of smell in dogs reacts to, savours and needs for the fullness of its life. For the domestic dog, nosework beats telly-watching by a mile!

The scenting powers of dog have attracted the attention of the scientists; Droscher in 1971 found that a barefooted man leaves roughly four billionths of a gram of "odorous sweat substance" with each step he takes. Budgett in 1933 found that water formed 99% of such a gram in the first place. In locating this minute sweat sample, the tracking dog has to overlook the accompanying, conflicting and much more powerful surrounding smells - animal, vegetable and mineral...and most men on the run wear shoes! The experiments of the Russian psychiatrists Klosovsky and Kosmarskaya on puppies led them to believe that the senses of smell and taste were so interconnected that they were virtually acting as one, and, could in general, act interchangeably.

I have noticed when using dogs on a trail that the dog's head is carried higher during morning tracking, perhaps because the air is rising bringing the scent with it. It is also noticeable that scenting ability varies from individual to individual dog even within a breed; I suspect too that it is the determination and sheer persistence of the Bloodhound which makes it so effective at following cold trails, just as much as its scenting powers. Using Labradors, as tracker-dogs in the Malayan emergency, showed me that scenting prowess isn't enough by itself; you need a fanatic like a Bloodhound for really testing trails. Although the contemporary physique bestowed on this breed in the show ring is a serious handicap in the field.

A dog's sense of smell is probably several hundred times as powerful as ours. The reason for this lying in the fact that the areas inside a dog's nose which detect smells are roughly fourteen times larger than the equivalent areas in man. But a detector needs to be matched by a comparable performance in a receiver; the part of the dog's brain dealing with smell is proportionally larger and better developed than the human equivalent. One estimation gives a figure of forty times as many brain cells connected with the detection and perception of smell in the dog as in the human brain. The sheer sensitivity of the nose of dog allows it to specialise in hunting deer or fox, otter or hare, man or truffles and to locate avalanche victims, drugs, the wounded on the battlefield, explosives, temporary graves, dry rot, melanomas, the onset of epilepsy...even "moonshine" in America.

The tracking ability of the dog has been used to show that identical twins produce an identical odour. A dog can follow the trail of either twin after smelling an article belonging to one of them, although cases have been recorded of a gifted dog actually differentiating between the two. This tracking ability can be impaired by temperature change, rain, humidity, frost, wind, competing odours and the sheer passage of time. But no human or machine produced by man would get on such a trail in the first place. This tracking skill backed by dog's response to training is a valuable element in the unique man-dog partnership. Pigs employed to locate truffles usually eat them!

The more perceptive writers on dogs have long appreciated the overriding importance of the canine sense of smell. Wilson Stephens in his quite excellent "Gundog Sense and Sensibility" has written: "To gundogs, with centuries of nose-consciousness bred into it, noses are for serious business, eyes merely come in useful occasionally"... going on to state that he had never needed to teach a dog to use its nose but usually had to teach one to mark the fall of game using its eyes.

"Wildfowler" in his "Dog Breaking" of 1915 gave his list of setter qualities in this order; "Nose, pace, energy, style and indomitable endurance"...no doubt in his mind of the value to man of dog's sense of smell. But to limit scenting powers just to the nose is not entirely correct. In his informative "The Mind of the Dog" (1958), R.H.Smythe recorded this information: "Now, odours, scents or smells represent the delights of paradise to every dog...it is well known that delicate smells make the mouth water. Saliva dissolves the scent-bearing vapours and so the dog not only smells them but also tastes them. It is believed that hounds use both smell and taste, especially when the scent becomes strong, and it is believed by many that when hounds 'give tongue' they are actually savouring the delightful odour as it dissolves in their saliva." In pursuit of this belief our ancestors utilised the "shallow flew'd hound" to hunt by sight and scent, in that order, as a "fleethound" and the "deep-mouthed hound" as a specialist scenthound.

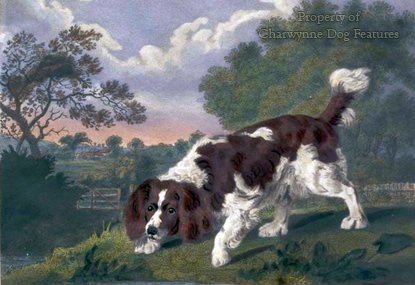

There is a link too between well-developed sinuses and the ability to track. The best trailers have the skull-conformation to allow good sinus development, adequate width of nostril and good length of foreface so that there is sufficient surface between the nostrils to house the smell-sensitive lining membrane. Scenthounds, gundogs and other hunting dogs depend on the shape of their skulls for their acute smell-discrimination. In pedigree breeds, the wording of the description of the skull in the breed standard can therefore directly influence the scenting prowess of the dog. The narrower skull of the terrier leads it to prefer to hunt by sight, show less interest in following a trail of scent yet, through selective breeding, show enormous interest in scent coming from below ground.

Imagine the delicacy of scent that allows a gundog, at some distance, to distinguish between a partridge and a lark, a pheasant and a woodcock. General Hutchinson, writing at the turn of the century in his classic work "Dog Breaking" advised hunting pointers and setters together, stating on the subject of scent that..."on certain days -- in slight frost, for instance, -- setters will recognise it better than pointers, and, on the other hand, that the nose of the latter will prove far superior after a long continuance of dry weather"...The different breeds often display definite strengths in such a way and so too do individual dogs.

Following a trail "hot-footed" at great pace demands not only a "fast nose", i.e. superb coordination between detection and reaction, nose to brain, but also the anatomical capability of physical response too. The legendary foxhound, Mr. John Smith-Barry's "Bluecap (1759)", took part in a famous match-race in 1762 over a four-mile distance on Newmarket racecourse. The ground was reportedly covered in just over 8 minutes. Sixty horses started with the four foxhounds but couldn't last the pace, only twelve finishing. Yet the hounds had to run and follow a trail! "Bluecap", it was alleged, covered ground at a mile every two minutes, approximately the speed of a Derby winner. I wonder what time this hound would have achieved just running with its head up. His 3 year-old daughter, incidentally, came a close second in this match.

But "flying the country" is not the essence of scenthound work; the skill in unravelling a confused scent, the music of the hounds and the teamwork of the pack is the core of hunting pleasure with hounds following by scent. "Questing and melody" in such hounds has long been greatly valued and the considerable skill needed to pursue poor scent always much admired. In stag-hunting, the most trusted hounds, the tufters, exercise great scenting skill in deciding on the right line to get the pack laid on and the desired quarry isolated from the remainder; only a dog can do this.

It could be that with the contemporary pressures on country sports, not just those arising from differing social attitudes but more from the increasing loss of country in which packs of hounds can operate, we need to find new outlets for hounds which follow scent. Hound trailing in the Lake District gives great pleasure to both people and hounds and offends no one. Perhaps a revival of match-races in which foxhounds or comparable breeds take part in speed trials on draglines in the wake of "Bluecap's" feat would fulfil a need. So too could scent-matches in which the slower foothounds could prove the quality of their nosework on confused trails, where time was less important than accuracy. Come on you fanciers of staghounds, harriers, Bavarian mountain hounds, Dumfriesshire foxhounds, Hanover scenthounds, Grand Bleu de Gascogne and Hamiltonstovares; the heritage is there and the instincts merely dormant. Shelley, albeit in a different context, summed up such a situation most aptly:

..."You will see hunt -- one of those happy souls

Which are the salt of the earth, and without whom

This world would smell like what it is -- a tomb."