152 Decoy Dog

THE DYING ART OF DECOYING

by David Hancock

The invention of firearms and the subsequent improvements in the range and accuracy of guns in the shooting field brought about a large measure of redundancy in the ancient art of decoying, now rarely known about by sportsmen let alone practised. We still of course put out bird-dummies to entice feathered game like woodpigeon and duck, but it is extremely rare to come across decoy-dogs at work, despite their time-honoured employment in this field in many different countries. In Canada,in Holland and certainly in one place in England however, this ancient canine skill is being perpetuated.

The invention of firearms and the subsequent improvements in the range and accuracy of guns in the shooting field brought about a large measure of redundancy in the ancient art of decoying, now rarely known about by sportsmen let alone practised. We still of course put out bird-dummies to entice feathered game like woodpigeon and duck, but it is extremely rare to come across decoy-dogs at work, despite their time-honoured employment in this field in many different countries. In Canada,in Holland and certainly in one place in England however, this ancient canine skill is being perpetuated.

From medieval times the antics of the "tumbler" have been well documented, although I notice that writers on lurchers often use the pseudonym "tumbler" whereas this should, more accurately for them, be "stealer". The tumbler aroused the curiosity of furred and feathered game by its histrionic performance, lowering their guard, reducing their caution and then enticing them, sometimes into nets or within range of the guns, and sometimes seizing them itself.

In Bewick's "A General History of Quadrupeds" of 1790, the tumbler was described as being ..."so called from its cunning manner of taking rabbits and other game. It did not run directly at them, but, in a careless and inattentive manner, tumbled itself about till it came within reach of its prey, which it always seized by a sudden spring."

Dr.Caius, in his long letter to the naturalist Conrad Gessner of 1570 used these words to describe similar antics..."When he comes to a rabbit-warren, he does not worry the rabbits by running after them, nor frighten them by barks, nor show any other marks of emnity, but casually and like a friend he passes by them in artful silence, carefully noting the rabbits' holes..."

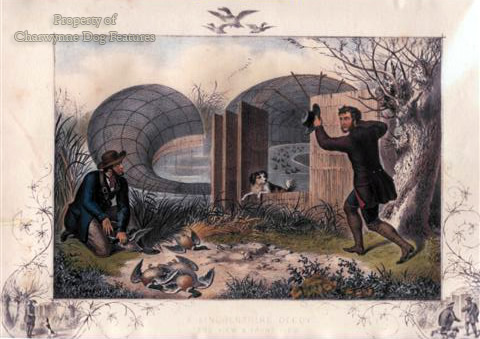

Phrases like "careless and inattentive manner" and acting "casually and like a friend" describe most perceptively the crafty technique of the decoy dog whether "tumbling" or leading ducks astray. The dog used as a decoy in duck hunting often worked in partnership with tame ducks to entice their wild relatives along ever-narrowing netted or caged channels until they were made captive. Jesse in his exhaustive "Researches into the History of the British Dog" of 1866 described how in the fens of Essex dogs resembling the "colly" were used with tame ducks to entice wildfowl into tunnel-nets.

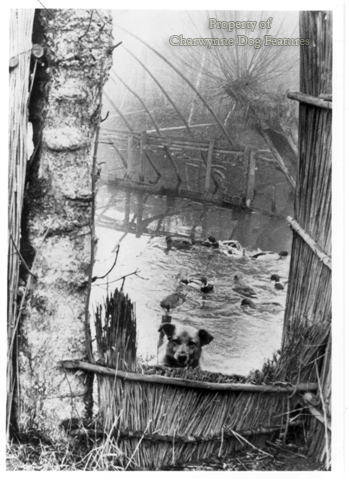

The skill of the decoy dog lies in giving the inquisitive ducks only fleeting and seemingly tantalising glimpses of its progress through the reeds and undergrowth, taking great care never to frighten them or even give them cause for suspicion. Before the use of firearms and indeed in the days when their range was very limited, these dogs must have been enormously valuable to duck-hunters.

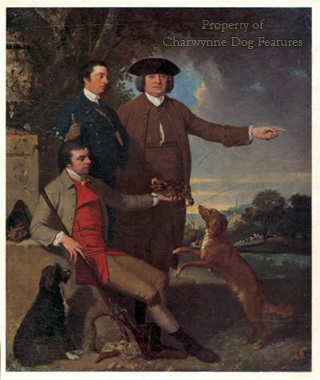

The distinctive feature of dogs used in this way was the well-flagged tail. Their colour was usually fox-red, leading to some being referred to as fox-dogs, partly also because foxes will entice game by playful antics in a very similar vein. Clever little foxlike dogs have been used in many different countries in any number of ways in the pursuit of game: in Finland, their red-coated bark-pointer spitz transfixes feathered game by its mesmeric barking whilst awaiting the arrival of the hunters; in Japan, the russet-coated shiba inu was once used to flush birds for the falcon and the Tahl-tan Indians in British Columbia hunted bear, lynx and porcupine with their little black bear-dogs, which were often mistaken for foxes.

At the end of the last century "ginger 'coy dogs" were frequently to be seen alongside the lurchers in gypsy camps, especially in East Anglia. Because no pedigree breed in this mould has been handed down to us, very little reference is made nowadays to these gifted and at one time invaluable dogs, rather as the ancient water-dogs are rarely acknowledged in the histories of our gundog breeds. Both decoy-dogs and water-dogs were usually handled by the humbler hunters like gypsies and so very little has been written about them.

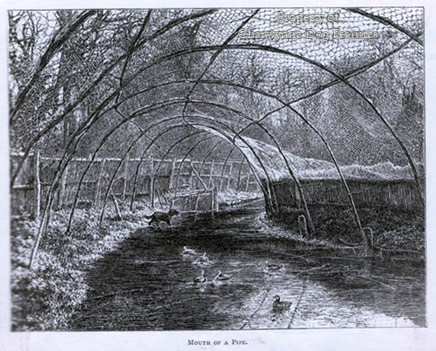

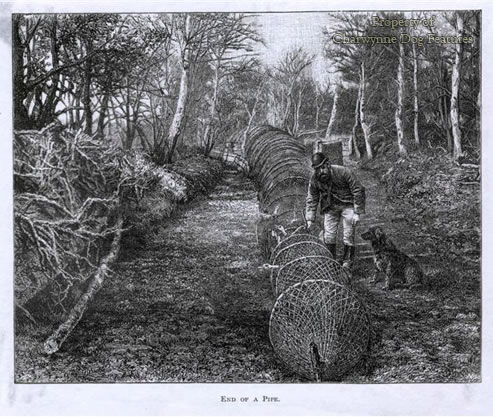

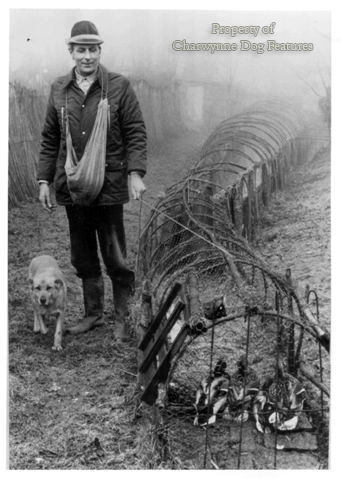

In Europe it seems that the Dutch in particular had perfected the art of duck decoying, with the word itself coming from their word endekoy, a duck cage. The first duck decoy in Britain was built by a Dutchman, Hydrach Hilens, just over three hundred years ago in St.James's park for Charles the Second. Such a decoy usually consists of a small shallow pond secluded by trees with a number of "pipes" leading off it, each about 60 metres long. These pipes or caged tunnels are six metres wide and four metres high at their entrance but narrowing right down to the decoyman's net.

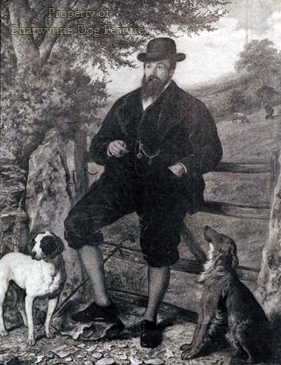

Along the curve of the pipe the decoyman (or kooiker in Holland) is concealed behind reed-screens. One of the few remaining in Britain is a joint venture between the National Trust and the Berkshire,Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire Naturalists' Trust at Boarstall. This decoy is marked on the 1697 map of the Manor of Boarstall in the Buckinghamshire County Record Office. Tame "call ducks" are no longer used here but Daniel White who once worked this decoy for over 60 years used six large Rouen call ducks. The yearly average of duck taken at the end of the last century was 800. I believe there are only four kooikers still operating in Holland but they have retained their specialist breed of decoy dog, the kooikerhondje, a small red and white spaniel-like dog with a tail very much like that of the Cavalier King Charles spaniel. We appear to have lost our native red-coated decoy dog which surely could still have been useful if only to those wishing to ring,photograph,paint or just study wild duck.

In Canada, probably taken there by European colonists, there is the Nova Scotia Duck-Tolling Retriever, a golden-red medium-sized dog with the distinct look of our golden retriever about it. This Canadian dog is about 20" at the shoulder with a compact muscular build, alert, agile and determined, a strong swimmer, easy to train and a natural retriever. To be a successful duck-toller, such a dog needs a playful nature, a strong desire to retrieve and a heavily-feathered tail which is in constant motion.

The Canadian kennel club recognised the tolling retriever as a distinct breed in 1945 but since then only about 1500 have been registered. There are around 60 of the breed in the United States. Avery Nickerson has been breeding, training and hunting with tolling retrievers for most of this century from his Harbour Lights kennel in Yarmouth county, Nova Scotia. He builds blinds or screens on the shore of his local lake in areas where ducks come ashore from deep open water. He then creates a winding path from the screen to the shore of the lake. When ducks swim close by he begins to throw sticks for one of his dogs to retrieve. The ducks are attracted by the waving tail of the disappearing dog and come closer to investigate.

The skill of the hunter lies in throwing the stick for the dog the right distance at the right moment so that the ducks are not frightened away by the menace of an advancing dog, but made curious by the enticing waving of its bushy tail. The dog makes a normal retrieve of the stick but does so in a playful manner with plenty of tail-wagging. This decoy dog does not entice the birds by deliberately frolicking about, as foxes have been seen to, but is used essentially as a retriever of sticks. This playful retrieve however does lure the duck within range of the hunter's gun. I strongly suspect that this Nova Scotia duck-tolling retriever is our "ginger decoy dog" exported and I think it likely too that the latter was part-ancestor of the modern breed of gundog, the golden retriever.

So the next time you throw a stick for your golden retriever to bring back to you, you may be re-enacting the role for which the dog's ancestors were greatly valued rather than merely idling away time and providing exercise. The golden retriever always seems to have its well-furnished tail in perpetual motion and this may come from its long-lost role with the decoyman. Perhaps some enterprising wildfowler will now try his hand at reviving what may well be a dormant instinct in the breed.

So the next time you throw a stick for your golden retriever to bring back to you, you may be re-enacting the role for which the dog's ancestors were greatly valued rather than merely idling away time and providing exercise. The golden retriever always seems to have its well-furnished tail in perpetual motion and this may come from its long-lost role with the decoyman. Perhaps some enterprising wildfowler will now try his hand at reviving what may well be a dormant instinct in the breed.