137 BLACKENING THE MASTIFF

BLACKENING THE MASTIFF

by David Hancock

Bertrand de Guesclin, a 14th century French soldier, who fought for Charles V against the English during the One Hundred Years War and one of the finest leaders in battle of his time, was so respected by his English opponents that they called him 'The Black Mastiff'. This was an indication too of the regard for Mastiffs at that time. In his Henry V, William Shakespeare wrote 'This island of England breeds very valiant creatures, Their mastiffs are of unmatchable courage'. Sadly, today, our Mastiff breed is prized mainly because of its size and weight. And in the Kennel Club's rings you will never see a black one.

Bertrand de Guesclin, a 14th century French soldier, who fought for Charles V against the English during the One Hundred Years War and one of the finest leaders in battle of his time, was so respected by his English opponents that they called him 'The Black Mastiff'. This was an indication too of the regard for Mastiffs at that time. In his Henry V, William Shakespeare wrote 'This island of England breeds very valiant creatures, Their mastiffs are of unmatchable courage'. Sadly, today, our Mastiff breed is prized mainly because of its size and weight. And in the Kennel Club's rings you will never see a black one.

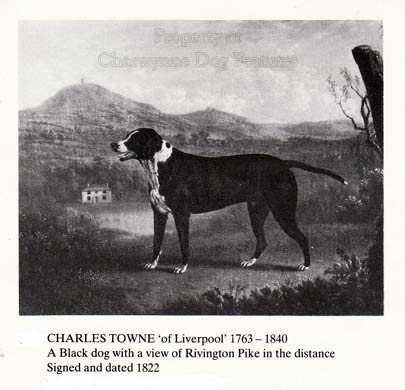

This is not historically correct. The modern breed, according to its KC standard, can only be apricot-fawn, silver-fawn, fawn, brindle or 'non-standard', whatever that means. But Bewick, Buffon and Gilpin depicted Mastiffs two centuries ago that were black and white or mainly white. There are artistic depictions from the past too of pied (i.e. brown and white) Mastiffs; it is clearly also in the breed's gene pool and crops up in litters. How sad to read therefore of the Old English Mastiff Club's decision in 2015 to outlaw anything other than the colours currently set out in the more-than-flawed Breed Standard. Genetic diversity in breeds operating within a closed gene pool for a century is thereby being severely reduced. This breed needs new blood more than most other pedigree KC-registered breeds.

Foreign mastiff breeds like the Broholmer, the Neapolitan, the Fila Brasileiro, the Tosa, the Cane Corso and the Great Dane can feature a black coat. But now, a Welsh enthusiast, Gareth Williams of Bishopston, Swansea, with his wife Claire, is promoting his line of black Mastiff, which he considers is a descendant of the Welsh holding dog or gafaelgi, used by butchers to seize wayward bulls and before that to pull down big game. Douglas Oliff in his The Mastiff and Bullmastiff Handbook of 1988, mentions two fifteenth century references which translate from Welsh as, 'what good are greyhounds, two hundred of them, without a gafaelgi' and 'the gafaelgi takes fierce hold of the stag's throat, and is black in colour'. Note the coat colour.

In his The Bullmastiff Handbook of 1957, Clifford 'Doggie' Hubbard, who knew a thing or two about Welsh dogs, recorded: 'As far as I know, the Mastiff (in Welsh, Cystawcci) was of two kinds, the Cadgi (or battle dog) and the Gafaelgi (or holding dog). The fact that the holding or gripping dog was included under the heading of Mastiff instead of Hound does not necessarily preclude his use in hunting, of course, but it does suggest early work as a guard and keeper's watchdog.' The holding or gripping dog, docga in Old English, dogue in French, dogge in German, perro de presa in Spanish, fila in Portuguese, was used all over Europe as a hunting mastiff on wild bulls, stag, bear, boar and even aurochs. They had to be agile to survive. They were strong-headed, powerfully-built, hunting dogs, never prized purely for their shoulder height or their weight. Gareth Williams's Mastiffs are not vast, lumbering, heavy-boned unathletic specimens, like the show ring exhibits, but strongly-built, muscular canine athletes, just as the true Mastiff should be. He deserves support.

His Mastiffs resemble the type depicted by Ben Marshall in 1799, a very large but agile, alert, soundly-built and strongly-muscled strong-headed but tight-mouthed dog. Far too many of the show ring Mastiffs cannot live an active life, they are simply too heavy, and they do not lead active lives. They can damage themselves just getting out of a car. No dog should be bred so heavy that it cannot live like a normal dog. No dog should be bred with built-in anatomical handicaps. In the pursuit of great size, many Mastiff owners overfeed and over-supplement their young dogs with vitamins and minerals. Obesity is a major threat to the well-being of Mastiffs. Any dog weighing nearly 200lbs desperately needs the soundest of physiques just to ensure a fulfilling life.

Historically, they were never that big. The great Mastiff expert of the 19th century, MB Wynn wrote in 1886 that 'the old English Mastiff, without the aid of foreign assistance, was never a large dog...' He was referring to the Alpine Mastiff, Tibet Mastiff and Great Dane blood which was introduced into our Mastiff to produce a much bigger dog. Another Mastiff expert, HD Kingdon wrote in 1883 'We do not believe in the purity of mastiffs over thirty inches...' Originally the Mastiff was a hound, a hunting mastiff used by medieval hunters on big game. In his classic The Master of Game, the oldest book in English on hunting, Edward, second Duke of York, put it very simply: 'A mastiff is a manner of hound'. But the Kennel Club does not agree, placing the breed in their 'Working Group'. What arrogance!

Gareth Williams's Mastiffs are around 26 inches at the shoulder and weigh 110lbs; he d oes not restrict his breeding to blacks, accepting any solid colour, but not favouring brindles or whites. So you can have a Welsh, German, Italian, Brazilian, Danish, Tibetan and Japanese black mastiff but not a black English one. You can however have a near-black English Mastiff in darkest brindle. Where is the rationale behind that? Black has been lost in Boxers and isn't favoured in show Bulldogs. In the famous 'Philo-Kuon' Bulldog breed standard of 1865 however, it stated that 'black was formerly considered a good colour...' Why not now? How many quality Bulldog whelps down the years have been consigned to the bucket purely on account of their coat colour? This is not wise breeding; it's colour prejudice.

oes not restrict his breeding to blacks, accepting any solid colour, but not favouring brindles or whites. So you can have a Welsh, German, Italian, Brazilian, Danish, Tibetan and Japanese black mastiff but not a black English one. You can however have a near-black English Mastiff in darkest brindle. Where is the rationale behind that? Black has been lost in Boxers and isn't favoured in show Bulldogs. In the famous 'Philo-Kuon' Bulldog breed standard of 1865 however, it stated that 'black was formerly considered a good colour...' Why not now? How many quality Bulldog whelps down the years have been consigned to the bucket purely on account of their coat colour? This is not wise breeding; it's colour prejudice.

In his informative and valuable Practical Genetics for Dog Breeders, leading geneticist Malcolm Willis has written: "If a colour is associated with a specific problem (as with MM) (i.e. the merle gene, DH) then there is good justification for avoiding or banning the colour. Where no such biological excuse exists bans are less justifiable...Those breeders whose breed allows any colour are advantaged and should preserve such advantages." Some colour prejudices come from quite primitive beliefs; Italian shepherds once regarded white pups as the only pure ones; Portuguese shepherds once believed that harlequin ones were pure; Turkish shepherds used to consider fawn with a black mask as a sign of purity. Having a very human preference for one colour is understandable; but, in a closed gene pool, it is unwise to ban a colour which once featured in that gene pool. Black Mastiffs are historically correct.

Imagine, if, in 1900, the Labrador fraternity had decided that, despite their gene pool, black dogs were to be disallowed. How many quite outstanding Labradors would have been denied to us as a direct result? However much we admire the yellows and the chocolates, the blacks have been the bedrock of Labrador excellence. The black Pointers of the Duke of Kingston once excelled but nowadays whole black Pointers don't seem to be favoured. Colour prejudice seems to flourish in dogdom. You can register silver, apricot, fawn or black Pugs but all of those coat colours except black in Mastiffs. The outside blood introduced into the Mastiff gene pool in the 19th century included that of the Great Dane and the Tibetan Mastiff, both of which can be registered as blacks. So the black gene is acceptable but not the colour when manifested. Genetic diversity, especially in a closed gene pool, is highly desirable. I know of no geneticist who supports the pursuit of coat-colour exclusions. It is irrational; it lessens the genetic health of a breed.

In Leighton's The New Book of the Dog (1912), WK Taunton, who kept a large kennel of Mastiffs for over forty years, wrote: "It has occurred that Mastiffs bred from rich dark brindles have been whelped of a blue or slate colour. In course of time the stripes of the brindle appear, but puppies of this colour, which are very rare, generally retain a blue mask, and have light eyes. Many such puppies have been destroyed; but this practice is a mistake...some of the best Mastiffs have been bred through dogs or bitches of this shade." Campaigns by breeders to restrict the gene pool by obliterating the rarer colours do harm to a breed. Surreptitious outcrossing also has to be concealed when coat colours betray the traditional coat colours in a litter.

Half a century ago, two leading Mastiff breeders also kept Newfoundlands; in the 1960s one winning Mastiff carried a distinct Newfie head. I just wonder how many black Mastiff pups were found, and never admitted, in litters over the years. Our distant ancestors bred good dog to good dog and handed down superlative dogs to us as a direct result. It is absurd when a black Greyhound whelp is welcomed but a black Mastiff pup is destroyed entirely because of its coat colour. A really fit black Greyhound with the sun shining on its gleaming coat is a sight for sore eyes. There aren't many solid-black short-coated breeds and a majestic black Mastiff would be quite impressive. In past times, richly-coloured near-black brindles like the Marquess of Hertford's Pluto (1830) and EG Banbury's Wolsey (1890) were strikingly good-looking dogs.

Sadly for dogs, far too many exhibitors in KC-sanctioned rings are show-men rather than dog-men; the rosette means more than the breed, with breed-improvement not on their agenda. At game fairs, country shows and companion dog shows I see pioneer-breeders trying, without doctrine or dogma, to produce quality dogs of a set type or a re-creation of a breed long spoiled by show-breeders. They will get nothing but scorn from the pedigree perpetuators, which is often totally unfair, because they regularly produce admirable dogs. Last year I saw several Mastiff-crosses which were far sounder dogs than the show ring specimens bearing the Mastiff name. This is a breed which screams out for improvement, even a new start. The blind pursuit of pure-breeding when the results don't justify it is not an exercise in livestock breeding but misguided eugenics. Breed sanctity can become breed insanity.

Our Kennel Club has made sustained attempts in the last five years or so to widen its mandate and extend its reach in keeping with its self-imposed leitmotiv of 'the general improvement of dogs'. Just as the KC once recognised and registered crossbred retrievers and game-finders, it should similarly attract the registration, on a separate register, of unrecognised breeds, such as Fell Terriers, Plummer Terriers, Sporting Lucas Terriers (already registered with the UKC of America), Dorset Olde Tyme Bulldogges and the Williams's Gafaelgis or Welsh Mastiffs. The owners of such dogs may not want to exhibit them to the KC's criteria but they deserve encouragement, they need support. Sniffy disdain does nothing for the general improvement of dogs, enlightened leadership can contribute a great deal. Why should a water spaniel from America, a newly-created spitz breed and an American variation of a Japanese breed obtain a higher priority than British breeds developing here? We need a Register of Emergent Native Breeds - and soon!

Emergent breeds are often much more virile and robust than many long-established breeds, probably benefiting from hybrid vigour. Far too many pure bred dogs suffer from man-imposed limitations which lessen the variety, especially within a closed gene pool. Restrictions on colour reduce the size of a breed's genepool and increase the perils of too-close breeding. A griege Weimaraner, a bay Hanover Scenthound or a sorrel Ridgeback look distinctive but such one-colour breeds come from a small base. The Mastiff does not and any restrictions on its breed livery are wholly whimsical. Mastiff expert, Wynn, was writing, over a century ago: 'Formerly the mastiff ran all colours, and were mostly pied with white...the question of colour looked at impartially, will at once be seen to be anything but a characteristic, all colours being admissable...for my own part I prefer the all-black, or the stone, or smokey fawn, with intense black ears and muzzle...' He was the best informed Mastiff breeder of his day.

Another famous Mastiff breeder, James Wiggesworth Thompson, of Southowram, Yorkshire, who started breeding Mastiffs in the early 1830s once wrote: 'I have seen mastiffs of exceptional character with more or less white on them, and think any judge ignoring a dog simply for this reason, would display fastidiousness to a fault.' It is this 'fastidiousness to a fault' which imposes quite artificial and historically incorrect limitations on coat colour in more than one distinguished breed. The black Mastiffs of the Williamses will receive nothing but suspicion, scorn and opposition from the Masiff breed fanciers of today. But it will be opposition not based on knowledge of the history of the breed but on show ring thinking, modern within-the-breed prejudice.

The latter with its closed mind and unthinking perpetuation of past folly can harm a breed. Any honest genuine breed fancier would honour its breed's past, respect the great breeders of the past and their wiser philosophy, so often intentionally overlooked in the blind following of mistaken contemporary dogma. Many a bright future has come from a dark past. And our Mastiff clubs and kennel clubs from around the world must now respect the Mastiff's origins and extended gene pool and themselves emerge from their 'dark past'.