127 THE NINETEENTH CENTURY DOG

THE NINETEENTH CENTURY DOG

by David Hancock

The Victorian era was a time of great change combined with remarkable stability. This was true in the world of the domestic dog just as much as in political and social life. Most of our native breeds of dog were established in this time. The influence of Britain throughout the world meant that British dogs were widely exported and valued abroad. The obsession of the ruling classes with field sports led to the development of superlative sporting breeds still renowned internationally. The introduction of dog shows, mirroring the livestock and hound shows already held in many parts of Britain, brought a new emphasis on the types of dog previously often only loosely collected into what became recognized breeds.

The Victorian era was a time of great change combined with remarkable stability. This was true in the world of the domestic dog just as much as in political and social life. Most of our native breeds of dog were established in this time. The influence of Britain throughout the world meant that British dogs were widely exported and valued abroad. The obsession of the ruling classes with field sports led to the development of superlative sporting breeds still renowned internationally. The introduction of dog shows, mirroring the livestock and hound shows already held in many parts of Britain, brought a new emphasis on the types of dog previously often only loosely collected into what became recognized breeds.

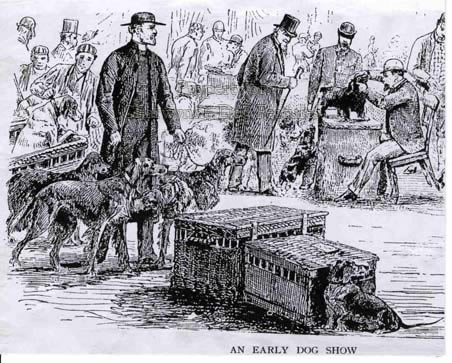

The founding of the Kennel Club in 1873 gave the world its first organisation of this type in the world. The first conformation dog show, held in 1859, led to a need for a controlling body, with a framework for the conduct of shows and a system for exhibiting and judging. Away from the show ring, the gentry favoured their setters and pointers, the humbler hunters their terriers and lurchers, the shepherds their clever herding dogs, the butchers their bulldogs and chimney sweeps their bull terriers. But ornamental dogs became more widespread too as small exotic dogs from distant countries caught the eye of wealthy patrons, sometimes attracting the royal eye too.

Sadly some breed-types were not to be perpetuated and disappeared: our decoy dog, the English Water Spaniel, the Devon Cocker, the Llanidloes Setter, the Smithfield Sheepdog and the Black and Tan broken-coated Terrier. Some breed-types were subsumed into developing breeds, especially the terrier breeds from more remote areas. This was the time when the pure-bred dog became king and for the first time in our history, dogs became prized not for what they could do but for what they looked like, a new dimension. But on the credit side, many breeds were saved by being brought into public prominence and promoted by dedicated fanciers. Order and credibility was introduced into the showing and judging of pure-bred dogs.

Royal patronage led to a number of breeds becoming either known for the first time or more widely favoured. Victoria ascended the throne at the tender age of 18 in 1837, her much-adored dog 'Dash' then being her devoted companion. After her Coronation, it was alleged that she hurried home to bath him. She was to favour and own several other breeds: Dachshunds, Skye Terriers, Scottish Terriers, Pomeranians, Pugs, Maltese and Collies. One of her Collies, Squire, was white, not a recognised colour in the breed today. Queen Victoria entered the initial Crufts dog show in 1891, with six Pomeranians, each weighing around 30lbs!

She had kennels built at Sandringham to house 60 hounds, the present Queen's Labradors being housed there today. Her heir, Edward VII, continued the family interest in dogs; he showed Chows, Skye Terriers and Basset Hounds, Queen Alexandra favouring Borzois and 'Japanese Spaniels' too. Edward's funeral procession was led by his close companion Caesar, a Fox Terrier. The Royal Family's dedicated interest in dogs undoubtedly affected public attitudes both to dogs and to the breeds they favoured, in the second half of the nineteenth century. For Crufts in 1893, the Czar of Russia sent over a splendid team of 18 Borzois, from his hunting kennels.

The nobility and landed gentry in Victorian times had a huge influence on dogs, sporting breeds especially. There were 200 packs of Foxhounds, with the Duke of Beaufort and Lords Donerail, Portsmouth, Coventry and Bentinck taking a keen interest. The Dukes of Gordon and of Richmond kept Deerhounds, as did Lords Seaforth, Tankerville and Bentinck. Lord Bagot showed Bloodhounds and Lord Wolverton ran a pack of them in Dorset, later sold to Lord Carrington in Buckinghamshire. The Marquis of Anglesea kept Harriers and Sir John Heathcote-Amory favoured Staghounds. Lord Lurgan's coursing Greyhound Master McGrath won 3 Waterloo Cups out of 4. The Duke of Atholl maintained a pack of Otterhounds. In Borzois, the Duchess of Manchester owned a huge specimen bred by Prince William of Prussia. The president of the KC was a duke, as was his vice.

In the non-sporting breeds, Lady Alexander favoured Collies, as did Princess de Montglyon. Lady Lewis and Lady Pilkington were members of the Bulldog Club, Lady Brassey is said to have introduced the black Pug to us. More famous in the Pug world were Lady Willoughby de Eresby and Lady Reid. The Duchess of Richmond promoted the Pekingese, with the 'Japanese Spaniels' drawing the support of the Countess of Malmesbury, Lady de Ramsey, Countess Wharncliff, Lady Probyn and the Countess of Warwick. Princess Sophie Duleep-Singh bred quality black Poms. The Mastiff was kept by the Earl of Oxford, the Marquis of Hertford and Lords Stanley and Waldegrave. In the terrier world, the Countess of Aberdeen patronised the Skye Terrier and the Duchess of Newcastle the Fox Terrier.

The noble families made a significant contribution to the gundog breeds: Lord Tweedmouth in Golden Retrievers, the Earl of Malmesbury and Lord Knutsford in Labradors, Viscount Melville in Curly-coats, the Earls of Sefton, Lichfield and of Derby in Pointers, the Duke of Gordon in his type of setters, the Earl of Tankerville and Lord Waterpark in English Setters and the Duke of Newcastle, Lords Middleton and Spencer in Clumbers. This is an impressive list but a very noticeable difference between the patronage of breeds of dog in Victorian times and now, is the almost negligible involvement of the nobility nowadays. Once, their interest guaranteed support for many breeds, a higher profile for the Kennel Club and the promotion of dogs for their sake rather than the bank balance. However I believe it is fair to state that the major contribution to the development of breeds as such came from 'lower down' the Victorian social scale, from the more plebian fanciers, as well as the dedication of the squires and yeomen breeders. In gundogs for example the likes of Llewellin and Laverack achieved greater impact, whilst in the Foxhound world the legendary 'Ikey' Bell restored soundness at a time when so many Masters of Foxhounds had lost their way.

Grand paintings in stately homes tell us much of the sporting and Toy breeds; you have to go 'folk art' to see depictions of the humbler Bull Terriers, Bulldogs, working terriers, lurchers and the pastoral dogs. Pointers and setters have had whole libraries of books devoted to them, but it was not until the latter end of Victoria's reign that the terrier and pastoral breeds, owned and worked by the humbler hunters and shepherds, received the literary attention they deserved. Bulldogs, long associated with the disreputable, were given prominence by breeders such as Bill George, and Bull Terriers, once developed for fighting purposes, fashioned by James Hinks, a Birmingham dog-dealer. Both breeds were favoured by sweeps, boxers and street-traders, as was the English White Terrier, now lost to us. Fox Terriers moved from the hunt stables to the drawing room, with the Rev. John Russell favouring his type in Devonshire.

The romanticization of the dog was widespread; the Rev Cuming MacDona magnifying the feats of the St. Bernard for example, before selling his St Bernard pups for comparatively large sums. Landseer depicted the rescue feats of the Newfoundland too, with many Victorian artists recording on canvas the more sentimental side of the man-dog relationship, at a time when cruelty to dogs was widespread. Dog-carts were banned, not out of concern for traffic flow, but out of compassion for the hard life inflicted on the dogs involved. Sadly too, freak dogs were sought by some misguided people, with dwarf specimens, the heaviest Mastiff, the tallest Great Dane, the Bulldog with the shortest muzzle, tiny terriers, minute Poms and miniature spaniels, often called trawler spaniels, being advertised. Foreign dogs became the desired possessions of those able to afford them - the Schipperke from Belgium, the Samoyed from Siberia, the Saluki from Arabia, the Tibetan breeds, the Borzoi from Russia (two being presented to Queen Victoria, as Russian Fan-tailed Greyhounds) and the Elkhound from Norway.

The seeking of exotic and exaggerated dogs, made fashionable in Victorian England has sadly continued; more breeds with a foreign origin are now registered with our Kennel Club than our native breeds. The Mastiff, misrepresented by a strangely-favoured dog 'Crown Prince' in Victorian shows, is now desired to display great bulk, the Bulldog a muzzle-less skull, the Basset Hound (away from the packs) the longest ears obtainable and the Pomeranian a tiny-ness never desired in its homeland. Fashion alone has led to some breeds being overbred and then neglected, as the copycat mentality was expressed. The Victorians set a precedent in these regards which has not been kind to dogs. But their enlightened approach to animal welfare, strongly supported by Victorian society, led to campaigns against the vivisection of strays and the muzzling laws, culminating in the emergence of The National Canine Defence League, founded in 1891 at Crufts dog show. Valuable work by the RSPCA led to dogs' homes being established. After one landmark cruelty case, The Morning Advertiser asked with sarcasm, how the society proposed to regulate the pace of hunting, adding that when even rat-killing and pigeon-shooting would be banned, a true Englishman would have no option but to emigrate. The pace of hunting is certainly different now.

The long reign of Queen Victoria witnessed huge changes to Britain and the world and the world of dogs was no exception, undergoing changes with far-reaching implications. Britain had a wide reputation as a breeder of livestock; the existence of Empire ensured that British sporting styles and social trends soon spread all over the globe. When, in the days before quarantine, British landed gentry went on sporting tours, their dogs went with them. When British livestock was exported, the herding dogs went too. When the British emigrated or went to work for extended periods in places like India, their dogs went with them. In the second half of the nineteenth century British dogs became known in most parts of the world.

This widening influence was accompanied by changes at home; dog shows became fashionable, field trials were introduced and both hunting and shooting became 'must-do' events in the countryside. Shows and trials brought a need for registration so that a dog's identity could be verified. As the range and frequency of shot increased so the needs of sportsmen in their supporting dogs changed too. In the hunting field the better breeding of hounds received much more attention. Companion dogs too were influenced by greater foreign travel and the subsequent introduction here of exotic breeds from distant places. At the same time came more focus on animal welfare, the moral repugnance towards some barbaric so-called 'sports', greater concern over the plight of street-dogs, draught-dogs especially, and a move towards more enlightened training and less 'breaking' of dogs.

Royal patronage and the obsession of the nobility with field sports gave some types of dog a higher profile. But the desire to produce dogs which closely resembled their parents and bred true to type, a fall-out of the show ring, led to the production of pure breeds. Of course, before that, breed-type was established in some cases with Greyhounds, Beagles, Pointers and Deerhounds usually looking like their ancestors. But from now on closed gene pools were to be respected and purity of breeding revered. For the first time in dogdom, it wasn't just a case of breeding good dog to good dog, both parents had to be registered and out-crossing was frowned upon.

This development has had a marked effect on the well-being of the dog. Breeding from a closed gene pool is fine when things are going well but disastrous when inbred faults and genetic flaws are encountered. The Victorian era may have given us the breeds but it has also given us the problems arising from in-breeding, conducted for a century in some cases. Our lives have been enriched by the breeds of dog handed down to us by our Victorian ancestors; now we must use scientific advances and increased veterinary knowledge to capitalise on and not be penalised by the admirable pioneering work done by the Victorians in the 19th century. This was the challenge for 20th century breeders and is now one for those in the 21st. One old sportsman once said to me: "The Victorians gave us the breeds, two World Wars ruined them!" Now is our chance to build on new scientific knowledge combined with native wit about dogs.