100 BURDENED BY BONE

BURDENED BY BONE

by David Hancock

Harmful Desire

Harmful Desire

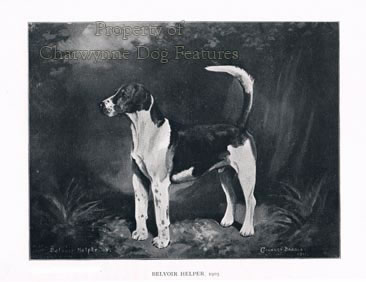

"The search for large bone is going to bring with it an obvious increase in growth rate which in turn renders the dog more liable to such problems as OCD, UAP or FCP..." Those words by Malcom Willis in his authoritative 'Practical Genetics for Dog Breeders' (Witherby, 1992) don't seem to impress dog-breeders perhaps as much as they should. Some breeds are actually prized for the weight of their bone, with many judges seeking heavy bone in exhibits, if their critiques are anything to go by. A century ago, Foxhound breeders lost their way and sought hounds with heavy dense massive bone, claiming that this feature provided stamina. They themselves however, when riding to hounds, rode hunters not cart-horses--and still managed to keep up! Their folly was subsequently exposed by a hound-expert from America, the legendary 'Ikey' Bell.

Identifying Need

Sadly, dog-breeding in purebred dogs is conducted, not on lines of desired and measureable improvement but on repeating the past, despite advances in scientific knowledge and a pronounced loss of type in some breeds. When, as part of my professional responsibilities, I ran a rare breeds' farm, I was able to benefit from a range of systems and recommended procedures, not utilised in adapted form by dog breeders. But even when breeding longhorn cattle, I never once heard the desirability of heavy bone mentioned in breeding programmes, and these were creatures weighing over a ton each. Strength and power in animals doesn't reside in bone size, as racehorses, antelopes and hyenas demonstrate only too vividly.

Standard Words

If you take a powerful breed of dog, such as the Mastiff or Bullmastiff, then compare its breed standard to the remarks made in judges' critiques, you can soon spot different requirements. The breed standard of the Bullmastiff makes just one reference to bone in its wording: the forelegs are expected to be 'well-boned'. The 'general appearance' section demands a dog that is not cumbersome; the hindquarters must not be cumbersome. The 'characteristics' section demands a dog that is active. There are no words in the breed standard to demand heavy bone, great bone, outstanding bone (whatever that is!) or substantial bone. But 'bone-headed' judges rush to find it!

Critical Stress

These extracts from thirteen recent critiques covering Bullmastiff exhibits make my point for me: "He had the best bone of the puppies I was considering"; "...outstanding bone"; "...great bone"; "...well-off for bone"; "...good bone"; "...super bone"; "...well-boned"; "...good bone throughout"; "...she is heavily-boned"; "...with plenty of bone"; "...could have more bone for his size"; "...terrific bone"; "...lovely bone"; "...with adequate bone". I'm glad about the latter, for surely the dog would have fallen over without it! Were these judges judging to the standard? Most animals with heavy bone are cumbersome and lack activity, two features undesired in the standard for this admirable breed.

Confused Judges

I don't believe the words in these quotes have any value for the novice breeder but, to me, they reveal confusion amongst judges. Strength, power and endurance do not reside in heavy bone, as any dog-sledder will tell you. To breed dogs with bone heavier than nature intended is asking for trouble, as the statistics on hip and elbow dysplasia, cervical vertebral malformation and osteochondrosis sadly demonstrate. But if the prototypal Bullmastiffs didn't display heavy bone and the breed standard doesn't authorize it, in whose name are judges seeking it when judging the breed? The situation in some other big breeds is even worse. The Mastiff of today seems to be bred for beef not any previous canine function; a Mastiff exhibitor at Crufts once boasted to me of the heaviness of his dog's bone but heavy bone is not required in the Mastiff's standard.

Indirect Cruelty

Hip and elbow dysplasia are painful and potentially crippling malformations of the joints. Many elderly humans know only too well the appalling discomfort of arthritis. To breed dogs of such body weight and bone density that they suffer cruelly from such afflictions is hardly admirable. But if show judges are actually rewarding massive bone, then cruelty to dogs is seriously being encouraged. In his valuable book 'The Anatomy of Dog Breeding' (Popular Dogs 1962), exhibitor and vet RH Smythe writes: "When a judge picks a dog out of a breed class for honours because he considers that it has better bone than its rivals, he is probably under the impression that the bones of its limbs (and he usually considers the fore limbs from elbow to knee) are thicker and stronger than those of other exhibits...it is only the mineral content of the outer casing which gives strength to bone...we must not delude ourselves into imagining that the increase of 'substance' implies extra thickness of bone.".jpg)

Shorthorn Era

Breeders of horses know that 'good flat bone' provides the quality not massively thick bone. Breeders of Foxhounds have learned the importance of bone from past follies. The late Victorian/Edwardian Foxhound breeders, perhaps in a vain attempt to surpass the superlative light hounds of such as Lord Bentinck, unwisely opted for over-boned hounds. Daphne Moore, a Foxhound authority, described such hounds as 'built on massive lines, with great bone, barrel ribs, knuckling over knees, very short upright pasterns ending in a foot which was round, fleshy and often pigeon-toed.' This was appropriately termed the 'shorthorn' period in hound breeding and thankfully it was soon abandoned. It was abandoned because it handicapped the hounds.

Needless Weight

The accomplished hound breeder Sir John Buchanan-Jardine once gave the view that 'Great weight of bone is unnecessary and rather a hindrance than the reverse...' It is of course the muscles which control the bones not the other way round; muscular development is far far more important than the thickness of the bone. It is a lazy response to state that 'what applies to Foxhounds doesn't apply to my breed'. The lessons learnt by any breeder in any field are worth heeding. To prize a dog mainly because of its weight is astonishingly shallow. To boast of an unsound dog's shoulder height and poundage is, to me, a sure sign of a limited personality. To be proud of a sound big dog is surely, in the larger breeds, every good breeder's aim; leave size-boasting to the socially inadequate.

Breed Need

It is worth noting the requirements for bone in the breed standards of the heftier breeds. The requirement is so often, as Smythe remarked, perceived as a forequarters' feature. The Pyrenean Mountain Dog, for example is required to have, in its forequarters, heavily-boned forelegs. The forequarters of the St. Bernard have to be strong in bone, those of the Tibetan Mastiff to be strongly boned, those of the Rottweiler need plenty of bone. The bones of a Mastiff's forelegs have to be large boned, the Leonberger's, the Maremma's and the Komondor's well boned, the Estrela's strongly boned and the Bouvier des Flandres's heavy boned. But shouldn't it all be a matter of degree? Does a Bouvier really need heavier bone than a Mastiff or a St. Bernard? Should breed standards not be coordinated and comparable?

Dated Standards

In The Times of 1805, an advertiser posted for sale a pack of 'boney' Harriers. He probably meant, in the language of that time, hounds with well-boned forelegs. Some breed standards were drafted over a hundred years ago; do the words used then have the same meaning now? In the famous Philokuon standard for the Bulldog, of 1865, the forelegs were required to be 'stout'; this word subsequently came to mean both corpulent and steadfast. Nowadays it usually means sturdy or resolute. A stout-legged Bulldog could be sturdy from excessive bone or well-developed muscle. I suspect that many breed standards have retained the reference to bone in their standards without the update needed, either for clarity or on health grounds.

Draught Dog Need

It is unthinkable for the legs of a breed like the Bernese Mountain Dog to have anything other than stout legs, although its breed standard doesn't actually ask for sturdy or chunky legs. All the draught dog/flock guarding breeds display strongly-built legs, although those of the Spanish Mastiff are, for me, over-boned in the show ring specimens. There is a sound reason for such dogs to be substantial. Dogs which protected sheep on a 500 mile journey, the 'transhumance' type, needed long legs to produce fewer strides, great body mass to endure a shortage of food and the size to withstand weather, disease and accidents along the way. A breed like the Mastiff however never needed such bulk; it was a hound.

Mastiff Needs

This breed was re-created in the 19th century using the blood of the Smooth St.Bernard, the Tibetan Mastiff and the Great Dane. The first two named were of the transhumance type, heavily-built dogs for sound historic reasons. Portrayals of Mastiffs before this infusion of foreign blood did not feature the heavy bone, considerable bulk and vast size of the contemporary dogs being passed off as Mastiffs. The function of dogs in the true mastiff mould was that of hunting dogs, as so many prints depicting the medieval hunt exemplify. The breed of Mastiff should never display 'great bone', huge bulk or be prized for its size. It should be an impressive big dog of activity, agility and strength. It should never ever be the canine equivalent of a cart-horse.

Shaped by Function

So often in dogs breed type lies in the eye of the beholder rather than in the brain. Pastoral dogs with the role of herding dogs should never be bred as 'walking coats', it insults their distinguished heritage and conflicts with true type. Similarly with the infliction of 'great bone' on breeds which firstly don't need it and secondly never had it. The big cats illustrate differing needs; the chase and catch species like the cheetah have light bone, the ambush and seize species like the lion have stronger bone, whilst retaining activity and speed in the dash. Function shaped our breeds; true breed type is always sacrificed when function is ignored, as the Bulldog exemplifies today.

Harmful Design

It forever disappoints me that the profession of veterinary surgeon doesn't bring with it a more developed desire to speak out when dogs are bred to a harmful design. They appear quite vocal on the docking of dogs' tails but are silent, and quite busy, on the castration of dogs for alleged 'behavioural' reasons. It is rare indeed to hear one hold forth on the perils of breeding 'shorthorn' dogs. Twenty years ago, one vet, Simon Wolfensohn, wrote on this subject in New Scientist magazine. He wrote: "There is no simple explanation for the shorter life-span of the giant breeds...apart from those that are destroyed because of bone problems early in life (usually due to faulty development of the growth plates of the bones or defects in bone mineralization) or because of severe arthritis...it may be that the hormonal mechanisations or other factors responsible for the giant size and heavy bone development of these breeds are intimately related to the aging process."

Animal Welfare

He took the view that St Bernards and Bloodhounds have a strong inherited tendency to acromegaly, a condition caused by excess production of growth hormone in the adult, which leads to heavier than normal bone structure, especially in the feet. Article 5 of the European Convention for the Protection of Pet Animals, at last receiving some official attention here, takes account 'of the anatomical characteristics which are likely to put at risk the health and welfare of the animals.' Before we reject as unwarrantable interference from Brussels such an Article, we surely need to remind ourselves of the times we live in. Animal welfare attracts a higher priority in contemporary life than hitherto. Do we really want unseemly scenes over dogs bred for harmful features, such as 'great bone' in breeds which never originally displayed it and are penalised by it?

Taking Action

The Foxhound fraternity needed an American hound expert to point out the folly of 'great bone' in functional creatures. The Cavalier was born out of an American fancier's concern over the muzzle-less bulging-eyed head of the King Charles Spaniel. Are we really going to wait for action from Euro-do-gooders before we realise the foolishness of seeking massive bone in animals, some originally designed to perform a function in the medieval hunt? This foolishness cannot be blamed on the wording of the standard; but bone-headedness is involved somewhere. Breeders of Bullmastiffs should be producing heavy hounds, not needlessly bulky inactive yard-dogs, demanding expensive veterinary care, leading shortened lives and plodding ponderously through their lives. Night-dogs had to be active!