98 UTILISING HOUNDS

UTILISING HOUNDS - Appreciating their skills

by David Hancock

Hounds around the world have not always been understood by writers, artists or even kennel clubs. Sir John Buchanan-Jardine MFH wrote a book ambitiously entitled 'Hounds of the World' in 1937 which only covered the pack scenthounds of France, Britain and America, ignored the scenthounds of all other countries and all the sighthounds. He also failed to mention the scenthounds which hunt 'chasse a tir' or for the gun. Artists down the centuries have often portrayed hounds in strange postures in their efforts to dramatize the chase. Kennel clubs divide the hound breeds very arbitrarily into scent or sighthounds, leaving no sub-division for 'par force' hounds, which hunted 'at force' using scent and sight, or for the heavy hounds which pulled down big game.

Hounds around the world have not always been understood by writers, artists or even kennel clubs. Sir John Buchanan-Jardine MFH wrote a book ambitiously entitled 'Hounds of the World' in 1937 which only covered the pack scenthounds of France, Britain and America, ignored the scenthounds of all other countries and all the sighthounds. He also failed to mention the scenthounds which hunt 'chasse a tir' or for the gun. Artists down the centuries have often portrayed hounds in strange postures in their efforts to dramatize the chase. Kennel clubs divide the hound breeds very arbitrarily into scent or sighthounds, leaving no sub-division for 'par force' hounds, which hunted 'at force' using scent and sight, or for the heavy hounds which pulled down big game.

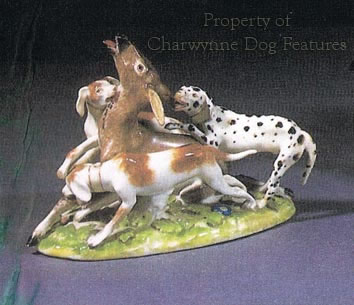

Par force hunting was eventually replaced in Britain by 'hunting cunning' in which the unravelling of scent became more important than the steeplechase of the former style. But 'fleet hounds' were preferred in the north of England, where par force hunting lasted longer. Contemporary breeds like the Great Dane, the Rhodesian Ridgeback and the Dogo Argentino are classic par force hounds, perhaps better termed 'running mastiffs'. It could be that the Dalmatian was once one too, its name possibly coming from 'Dama-chien' or deer-dog. The heavy hounds were the hunting mastiffs, used as 'seizers' to pull down big game.

Mastiffs were once used both in Scotland and Ireland to complement deerhounds and wolfhounds in the hunt. In his 'Hunting and Hunting Reserves in Medieval Scotland' of 1979, John Gilbert records: "Mastiffs are mentioned in those English clauses included in the Scots forest laws and were capable of attacking and pulling down deer. Wearing spiked collars, they were often used to attack wolves." In Lord Altamont's letter to The Linnaean Society of 1800, he states: "There were formerly in Ireland two kinds of wolfdog - the greyhound and the mastiff. Till within these two years I was possessed of both kinds, perfectly distinct, and easily known from each other."

It is difficult to imagine the Mastiffs of today's show ring being at all useful in such activity. But they might be bred more athletically if they were correctly classified as a heavy hound. Kennel clubs the world over would promote a better design for such dogs if hounds were sub-divided into four categories: those which hunt mainly by stamina, those which hunt mainly by speed, those which hunted 'at force' or the running mastiffs and the heavy hounds used as 'seizers' or hunting mastiffs. Hunting with hounds took many different forms and gave us the breeds we cherish today; we would honour their lineage more if we recognised their distinct functions.

Whatever 21st century thinking may bring to hunting with dogs, historians have demonstrated man's long need for dogs as pot-fillers in primitive times, his regard for hunting as a noble pursuit and the fascination it held for mankind all over the world. The Ancient Greeks would not have been impressed by a 'civilisation' which frowns on hare-hunting whilst tolerating hare-hounds being imprisoned in cages for 'scientific experiments'. They respected both the hound and its quarry--and revered the hunter. No educated person would regard the Ancient Greeks as uncivilized.

In his 'Hounds and Hunting in Ancient Greece' of 1964, Denison Bingham Hull wrote: "It was the very danger of the boar hunt that made it fascinating to the Greeks; victory was essential, for there was no safety except through conquest. It was that urge to display courage that made the boar hunt the highest manifestation of the chase for the hunter; that urge to show that he too was made of the same stuff as the heroes of the Iliad and the Odyssey, his forefathers, that compelled a man to take the risks and face the danger." I would place the courage of the hounds ahead of that of the human hunters.

Artists like Snyders, Tempesta and Desportes have recorded great hunting scenes for us and portrayed the dogs involved with their customary accuracy. But these portrayals have sometimes led to needless confusion. The boar for example was pursued by boarhounds but seized by catch-dogs or boar-lurchers, the boarhounds being too valuable to be risked 'at the kill'. It is likely that more dogs were killed on big game hunts than the quarry. Favourite hounds were protected with padded jackets of brown fustian (a thick hard-wearing twill cloth) or of bombazine (a twilled fabric of worsted and silk or cotton), with whalebone on the chest and belly to reduce the ripping action of the boar's tusks.

The wealthier hunters furnished their hounds with coats made of chain mail, on a quilted canvas and leather base. The Duke of Coburg's old sporting armouries near Gotha featured such coats. We should remember the sheer dash and reckless courage of the dogs which wore such coats. 'Extreme persistence' is now sadly one of the 'points' looked for by ignorant policemen when assessing powerful dogs under our shameful anti-dog laws. What a reward for centuries of selfless service doing man's bidding! We might strengthen the case for the defence in such sad prosecutions if the powerful determined dogs being persecuted were recognised, at long last, as hounds.

Because of Buchanan-Jardine's book, and that of George Johnston, his excellent 'Hounds of France' of 1979, we know a great deal about French hounds. But regrettably our knowledge of Baltic, Balkan, Swiss, Dutch and German, even American hounds, is far from complete. The most impressive entries at the World Dog Show in Helsinki a couple of years ago were the Finnish Hounds, handsome and functional. We all know about the Dachshund, the badger-dog, but little of the Dachsbracke, the badger-hound. We classify the Dachshund, an earth-dog, and the Finnish Spitz, a bark-pointer, as hounds but shove the German mastiff or boarhound into the Working Group. Strange!

Not surprisingly the hounds which hunt mainly by stamina look very similar in whichever country they developed. It is worth noting that the Bassets and Bloodhounds which still hunt in packs lack the exaggerations of the show ring specimens. Yet I have heard show breeders try to justify these exaggerations as actually having a field function! I am afraid I laughed out loud when the Bloodhound breeder at 'Discover Dogs' a few years ago informed me that the excess of wrinkle over his hounds' eyes was to ensure that the hound used its nose when working and not its eyes! And he said this with all the solemnity which his admirable breed is noted for!

Dachshunds may come in six varieties but the Swiss hounds come in even more forms. Unexaggerated and unsung, the Swiss hounds deserve wider recognition, ranging from the Jura hounds, showing French influence, the Lucernese, showing Bavarian influence and the Bernese hounds to the Swiss national hounds. Each of these four groups come in Beagle size (or Niederlaufhund, literally lower running dog) and Harrier size (or Laufhund). The latter resemble the German Steinbracke and the Dutch Steenbrak, the latter now saved from extinction by a small group of devoted fanciers. We may need similarly committed fanciers if our hunting packs are outlawed.

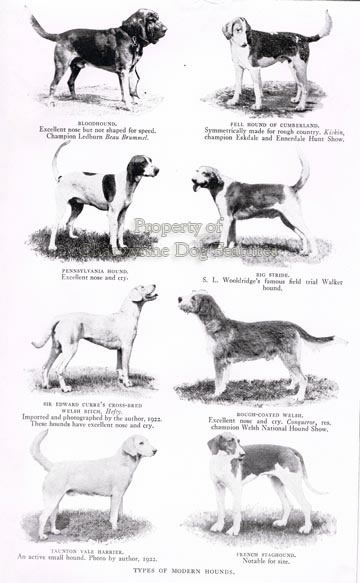

Just as the Kennel Club has recognised the Beagle, the Basset Hound, the Otterhound and more recently the Foxhound as breeds, we need to safeguard our Harriers too. On the Swiss model, the foxhounds and harriers of the packs would make up more than just two breeds. The black and tan Dumfriesshire Foxhounds, the rough-coated Welsh Foxhounds and the West Country Harriers could be considered to be distinct breeds. The Staghound of today is really just a Foxhound with a different function; we lost our huge Devonshire Staghounds a long time ago. The old 'Talbot Tan' hound however still crops up in litters. It is significant that Edward, second Duke of York, in his 'The Master of Game' of 1410 gave his view that: "The best hue of running hounds is called brown tan. I prefer them to all others..." Together with Fell Hounds (as distinct from Trail Hounds), which once benefitted from Pointer blood, and the English Basset, which has been revitalised with Harrier blood, this is a rich heritage of hounds to be lost.

Perhaps it is wishful thinking to expect all hunting breeds to survive. It is possible to find in Greek and Latin literature some sixty-five breed-types by name, although some are merely synonyms. The Greeks had hound breeders who insisted on the importance of pure bloodlines. But not all their hounds were Greek in origin, for the Greeks were a maritime people, with knowledge of the whole Mediterranean littoral and the Black Sea. Pollux and Oppian referred to a breed called the Iberian, associating it with the Spanish peninsula, not the Iberia of the Caucasus. In Italy there was the Ausonian, discovered by Greeks living in Naples, the Salentine and the Umbrian, able to run down game but not kill it.

In time the Greeks became aware of the hounds from the Rhineland called Sycambrians, the Pannonian hounds of northern Serbia and the Sarmatian hounds from southern Russia. Russian hounds were almost swamped by blood from our foxhound until Count Kisenski drew up a standard for the national hound in 1890, based on the famous Belousov pack, which originated in Tartary. There is probably truth in Betteloni's opinion of 1800: "...mastiffs from Tartary, molossians from Epirus, hounds from Flanders..." The Greeks described hunting mastiffs as 'Indian dogs' coming from Hyrcania by the Caspian Sea.

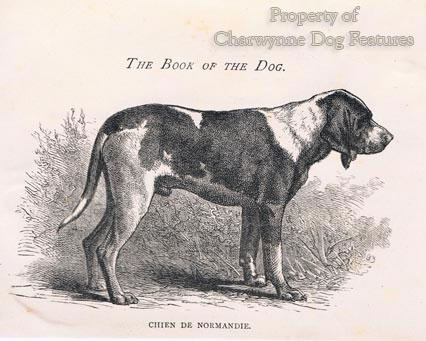

Arrian was aware of the rough-haired Celtic hounds, perpetuated today in the griffon breeds. Not surprisingly, France has lost some ancient hound breeds, the strapping Normandie, Virelade and Montemboeuf types, with the latter two perpetuated in the striking Gascon-Saintongeois. From Persia the Greeks imported the Elymaean hounds, the fierce Carmanians and the battle dogs of the Medes. From Asia Minor came the Carians, esteemed by Arrian as trackers with nose, pace and cry. As well as the somewhat overplayed Molossian hounds, Epirus produced the Acarnanian Hound, which, unusually in those times, ran mute.

The most important Greek hound was the Laconian, sometimes called the Spartan and referred to by Shakespeare. Just as interesting was the Cretan hound, which produced a variety called the 'outrunners' running free, under voice control only -- the first to do so in Europe until the end of the sixteenth century. The distinct breeds developed as hounds became specialist: the Locrians as powerful short-faced boarhounds, the Laconians as lighter hare-hounds, for example. Function led to design and we forget this at our peril. We also err in thinking of pack hounds as all thundering along with common skills; a pack is essentially a team.

Some foxhounds developed a skill for tracking on roads; one sporting magazine describing a particular hound as "a warranted macadamiser". Lord Henry Bentinck kept a detailed hound book, detailing each hound's special gifts; against 'Regulus 1861' he noted 'Regulus for roads'. Over a century ago, in France, Comte Elie de Vezins set out the blend of skills needed to compose a pack. He built his pack around a leader or chien de tete, possessing great scenting skill and pace, a natural leader, supported by three types of chiens de centre. The latter were made up of chiens de centre pur -- happy to follow and verify the leader, the chiens de centre avance -- to back the leader vigorously and keep the pack up with him, and the chiens seconds -- one or two hounds which press the leader, replacing him if he tires. He also mentions the chien de chemin, like Regulus, and the 'skirter' which always looks for short cuts -- brainier, perhaps, but not a team player.

We have over 300 quarry packs, mainly Foxhound but ranging from Beagle and Harrier packs to Fell and Mink packs. That's over 20,000 hounds, many with extraordinary scenting skills. We have rarely made use of these talents away from the hunting field. But we know of dog's ability to indicate buried bodies, hidden mines, dry rot in buildings, concealed drugs, the onset of epilepsy and the presence of melanomas. These hounds also have the health and virility much needed in some KC-registered hound breeds. It would be a supreme irony if the best bred, healthiest dogs in Britain were subject to a massive cull as a result of a campaign from an animal welfare society formed for the prevention of cruelty to such creatures! The Ancient Greeks gave us the word 'hubris' meaning excessive moral pride in humans or defiance of the gods, leading to nemesis. It appears to be contagious; but no dog has ever caught it!