33 THE ORIGIN OF THE SPORTING SPANIEL

THE ORIGIN OF THE SPORTING SPANIEL

by David Hancock

“Spaniels of both descriptions are brought into a kind of general use and domestic estimation. Their neat and uniform shape, their beautiful coats, their cleanly habits, their insinuating attention, incessant attendance, and faithful obedience insure them universal favour; but the sportsman feeling a double and superlative interest in their attachment and affection, loves them for their intrinsic merit, bestows the greatest pains and assiduity in training them for the field, and, when properly broke, and completely educated, he considers himself amply gratified by their ready services and indefatigable exertions in surmounting every difficulty that occurs in beating the various copses, brakes, covers, ditches, swamps, &c. in the pursuit of game. In addition to which accumulation of perfection, they seem to possess a degree of sagacity, sincerity, patience, fidelity, and gratitude, beyond any other of the species.”

“Spaniels of both descriptions are brought into a kind of general use and domestic estimation. Their neat and uniform shape, their beautiful coats, their cleanly habits, their insinuating attention, incessant attendance, and faithful obedience insure them universal favour; but the sportsman feeling a double and superlative interest in their attachment and affection, loves them for their intrinsic merit, bestows the greatest pains and assiduity in training them for the field, and, when properly broke, and completely educated, he considers himself amply gratified by their ready services and indefatigable exertions in surmounting every difficulty that occurs in beating the various copses, brakes, covers, ditches, swamps, &c. in the pursuit of game. In addition to which accumulation of perfection, they seem to possess a degree of sagacity, sincerity, patience, fidelity, and gratitude, beyond any other of the species.”

From The Sportsman’s Cabinet of 1803.

Origins

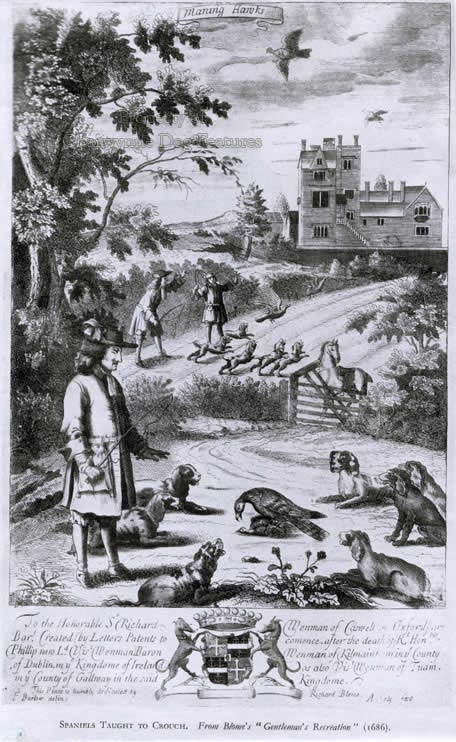

It’s the commonly held view that spaniels originated in Spain, mainly due to their name, allegedly a corruption of Espagne or espagnol. Perhaps this is just lazy thinking; there are many references to spaniels being imported into Spain in early times but not much on their export. Rather than linking the word spaniel with Spain, I suspect that it may well have come from the ancient French verb espanir, to crouch or flatten, rather like the Italian word spianare, to flatten. The latter could be behind the breed name Spinone, with the French setters becoming known as Epagneuls. In the Middle Ages, spaniels were usually used as hawking dogs (hounds for the hawk) and used with the net. There is an old Italian verb spaniare, to get out of a trap or net. Turberville, writing in 1575, often quotes Master Francesco Sforzino Vicentino, Gentleman Falconer of Italy, on the subject of ‘spanels’. It has been claimed that the spaniel family ranges from the large St Bernard (the Alpine Spaniel) right down to the small companion dogs, as favoured by our own King Charles. There is a distinct similarity of coat colour and coat texture right across this range, including the French epagneuls, described later. The trade in sporting dogs between Britain and France has long been a feature and I suspect that our spaniel, like our Pointer, originated there.

In his The Sporting Spaniel of 1924(written with Claude Cane), CA Phillips described shooting with local spaniels in Devonshire, writing: “At that time pretty nearly every hamlet along the coast from Dartmouth to Plymouth had its Spaniel of sorts running about…no covert was too thick or forbidding for them to face…Most of them were bred anyhow, but a few sportsmen kept their own strains, and it was wonderful how well they kept to type, and although some were a bit inclined to be curly in coat, and had their ears set on higher than we care for, many were quite typical cockers…They were pretty noisy when on their quarry, and very few would retrieve…” He has described how a type survived casual breeding, as well as the training challenge presented by such gundogs.

"The spaniel, in my opinion, is the most difficult of all dogs to break in a scientific manner, and this for one reason only, simply because his work takes him very frequently out of your sight in thick cover. You may say that he is naturally of a wilder nature than most sporting dogs...his duty being for the most part to 'roust out' his quarry..."

Those words from The Scientific Education of Dogs for the Gun, by 'H.H.', of 1920, give an instant impression of the task facing spaniel trainers, as well as indicating their time-honoured role. Sportsman, writer and breeder, the late Brian Plummer would no doubt have crossed a spaniel with a working sheepdog to obtain that measure of human control needed! I have long been surprised at how tolerant of a lack of steadiness many gundog men are of their spaniels. Half a millennium ago, in his informative The Master of Game, de Foix was writing: '...a spaniel, if he see geese or kine, or horses, or hens, or oxen or other beasts, he will run anon and begin to bark at them', going on to accuse them of 'so many other evil habits'.

Blaine, writing in 1807, stated that: "The variety of Spaniels are numerous. A popular distinction made between them by many writers is into Springers, Cockers, and Water Spaniels. Conventionally this distinction is understood, but critically it will not bear examination, particularly as regards the first two divisions." This is supported by the fact that the Welsh Springer has been called the Welsh Cocker for much of its history. Another authority of that time wrote that: "The true English Spaniel differs but little in figure from the Setter except in size." That great expert CA Phillips wrote early in the 20th century that: "...strictly speaking, all the different varieties of Spaniels are 'Springers', the name originally having been used in contradistinction to 'Setters'..."

“In referring to foreign gundogs it must at the outset be understood – as it is generally acknowledged by the sportsman of other lands than our own – that the British breeds used in the process of fowling are far superior to their foreign relatives…It is only fair to our fellow sportsmen on the Continent, however, to remember that our Setters, our Pointers, our Spaniels and Retrievers, have all been derived from strains imported into these islands from abroad.”

Robert Leighton, writing in his The New Book of the Dog of 1912, published by Cassell & Co.