18 SAFEGUARDING RURAL PROPERTY

SAFEGUARDING RURAL PROPERTY

by David Hancock

As an infantry soldier, I conducted anti-terrorist operations in a number of countries, mainly in the Far and Near East. These often involved searching for armed men in caves, outbuildings, house-to-house raids and in thick undergrowth. If you asked me to choose the type of type of dog I would prefer to accompany me on such dangerous activities, I would go for the broad-mouthed, mastiff type such as the Bullmastiff, the Dogue de Bordeaux, the Neapolitan Mastiff, the Perro de Presa Canario, the Tosa, the American Bulldog or the Fila Brasileiro. I would never go for the shepherd dogs however easy it is to train a German, Dutch or Belgian dog. When your life is being threatened who would you prefer to stand with you, a dog bred to guard sheep or a dog originally bred to pull down big game, such as buffalo, boar, bull and stag? Which dog would take the most punishment and fight on? It may only happen once!

As an infantry soldier, I conducted anti-terrorist operations in a number of countries, mainly in the Far and Near East. These often involved searching for armed men in caves, outbuildings, house-to-house raids and in thick undergrowth. If you asked me to choose the type of type of dog I would prefer to accompany me on such dangerous activities, I would go for the broad-mouthed, mastiff type such as the Bullmastiff, the Dogue de Bordeaux, the Neapolitan Mastiff, the Perro de Presa Canario, the Tosa, the American Bulldog or the Fila Brasileiro. I would never go for the shepherd dogs however easy it is to train a German, Dutch or Belgian dog. When your life is being threatened who would you prefer to stand with you, a dog bred to guard sheep or a dog originally bred to pull down big game, such as buffalo, boar, bull and stag? Which dog would take the most punishment and fight on? It may only happen once!

Of course, the surviving mastiff breeds are bred for show by breeders who rate appearance ahead of character and working ability, (Such dogs are also threatened by strangely-motivated policemen conducting anti-dog operations on the basis that any dog of substantial build, with a strong head and displaying 'extreme persistence' is a menace to the public. Yet a policeman with such attributes is rightly promoted!) The genes of the old 'holding dogs' are still there however and the key instincts merely dormant. One of the British mastiff breeds, the Bullmastiff, was of course developed as a gamekeeper's night-dog. It is odd though for today's breeders to extol this working past and then breed dogs which couldn't carry out such a role.

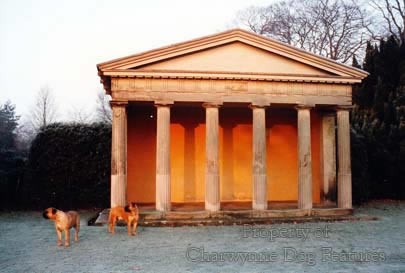

For two and a half years, in the mid 1990s, I used two Bullmastiffs to patrol the 1,000 acre country estate I was managing then. The estate embraced woodland, pastureland, a fast flowing river, formal gardens, the historic hall and the usual obstacles such as culverts, farm gates, stone walls and dense undergrowth, especially bracken and rhododendron. There was extensive public access and every type of farm animal grazing there. There was also plenty of game and a wide variety of vermin, including mink. The estate was threatened by vandals, poachers, trespassing picnickers, dumpers of illegal waste and thieves. My dogs had to be steady to stock, trained to ignore game and able to negotiate every kind of obstacle, whether clearing fences or wriggling under wire fencing. They had to operate under voice control, off the lead.

Some years before a large garden ornament had been stolen, and, before my dog-patrols, a couple of valuable items had been stolen from the Hall. There was a need for visible security and a perceptible deterrent. I had used dogs before, when serving as a soldier: Alsatians (before their renaming as GSDs) as patrol and anti-ambush dogs and Labrador Retrievers as tracker dogs and body/explosive detecting dogs. The requirements were of course very different indeed. The Alsatians were trained to indicate any human presence ahead during jungle operations; the Bullmastiffs had to spot human presence and react to identified activity, whether it was children inflicting minor damage or walkers quite legally on a footpath. In other words, they had to exercise discretion, perform beyond their training, never act on impulse, in short--think for themselves.

Much is written about intelligence in dogs. I had working sheepdogs for thirty years and they were superb dogs, easy to train, quick to respond, clever and eager to please. But which is the brighter dog, the one which is easy to train and will do exactly what it is told to do, nothing more, or one which may be less easy to train and more measured in its responses but thinks instinctively for itself? Is it really more intelligent to spend your days doing man's bidding, only using the training skills instilled and just responding to instructions, or, to assess each situation separately using inherited skills?

When using my Bullmastiffs as patrol dogs on an estate open to the public I could not possibly allow them to bark menacingly at a law-abiding rambler or threaten a child playing hide and seek. Luckily Bullmastiffs rarely bark and have a great love of children. Similarly, I did not want them to wag their tails at travelers seeking a future illegal campsite or livestock thieves carrying out a reconnaissance. The Bullmastiffs I used lived with us as pets; they were not trained to act as guard-dogs. Yet never once in two and a half years did they 'misread' a contact; they eyed suspicious characters with justified suspicion, they 'noticed' harmless human activity without their hackles going up or their throats rumbling with the beginnings of a growl. That is instinctive behaviour at work. A breed that doesn't bark reactively, as so many so-called guard-dogs do - often out of fear, is a bonus too.

On one early Sunday morning estate patrol, I came across two men on a fungi-foray, harmless trespassers it turned out. They were clearly very frightened of my dogs, and, in a friendly conversation, I asked them why. "Because they look so formidable!" said one. And a nine stone Bullmastiff with a strong head, black mask and muzzle and a steadfast gaze--which studies strangers with an uncompromising focus, is a definite deterrent. Snarling guard-dogs straining on a leash look savage; a powerful silent dog, unleashed but under voice control, eyeing you disconcertingly, leaves a lasting impression of controlled power.

How many Bullmastiffs are worked nowadays? The Kennel Club stages over 40 Working Trials every year. When was the last time a Bullmastiff was entered for one? At the Iceni GSD Club Working Trials Championship held in November 2000, a German wire-haired Pointer bitch beat 55 other dogs to become an International Working Trials Champion. This is not an event for gundogs but working dogs of any breed. The Staffordshire Bull Terrier fraternity is now running a Staffies' Pentathlon to include heelwork, scent test, agility, search squares, retrieve and sendaway tests. When are the Bullmastiff clubs going to organise a working trial for the breed?

I attended a Bullmastiff seminar a couple of years ago, where the principal speaker (strangely regarded as a breed expert) argued that to be a successful night-dog the dog had to weigh over 120lbs and had no need to be able to jump fences or stone walls! The most successful night-dog was Thorneywood Terror and he weighed 90lbs. His owner, W Burton, wrote on night-dogs that "He ought to be able to jump a gate with ease." Another famed night-dog 'Osmaston Daisy' weighed 88lbs. The esteemed pioneer breeder Moseley always stressed that a Bullmastiff should be active. His 'Farcroft Fidelity' was described by the knowledgeable Robert Leighton in 1924 as being as "active as a terrier, with hindquarters that would not disgrace an Alsatian". Sadly there are many Bullmastiffs lacking 'activity' in the 21st century.

For those who favour the breed of Bullmastiff and wish to ensure its future there is a challenge to be met. For any breed to have a long-term future its function has to be perpetuated. In the past function dictated form; the Bullmastiff of today wasn't developed out of breeder-whim or cosmetic appeal. The breed developed in the hard unforgiving world of function - if a dog was incompetent it didn't get bred from. This hard uncompromising world created breeds, decided type and shaped the physical design. In today's show scene arguments about eye-shape, tail carriage and coat colour can be indulged in. But in the medieval boar-hunt or on a lonely gamekeeper's round, the performance of the dog decided whether it was bred from or not. We have come a long way from such demanding criteria, perhaps too far.

Bullmastiffs may not be instinctive retrievers; mine could never see the point of retrieving an object only to see it thrown away again! They may not be built for agility work or temperamentally suited to automaton-dog activities like heelwork. I don't want my dogs to glue their heads to my knee. I very much admire and treasure the Bullmastiff's desire to know why it is required to carry out an instruction. Give me a thinking dog ahead of a clockwork model any day! As the great night-dog man Burton said a century or so ago: "Teach the dog to rely on himself". But we really should exercise their tracking, searching and detaining skills.

A number of breeds take part in Schutzhund or protection dog work. I suspect that the Bullmastiff would instinctively 'down' a man rather than worry an arm protected by a canvas sleeve. Early in the last century, a London vet, Charles Peirce, used to encourage his Bullmastiffs to 'down' a man on command. Eric Makins, the breed authority of the mid-20th century, admitted that Peirce taught him more about dogs than any other person. Peirce had much-respected Bullmastiffs. Moseley sent his bitch Farcroft Faithful to be mated to Peirce's Shireland Vindictive, to produce Farcroft Fidelity, a building block of the emergent breed. Shireland Vindictive's sire was a Bulldog, Wellington Marquis. But Peirce's most celebrated Bullmastiff was a brindle called 'Lion', descended from a famous nightdog Osmaston Viper.

Peirce had a fenced-off 'ring' in his yard and he would wager against any man being able to stay on his feet when opposing 'Lion' for just five minutes in this ring. 'Lion' never lost a wager for his owner despite many takers. The dog never harmed his 'challengers', just put them down and 'held' them until ordered to release them. This is instinctive behaviour for a 'holding dog'. It is instinctive behaviour which service-dog providers have never capitalised on. A criminal held by one arm can still fight or even wield a knife or fire a gun. It is a different matter if the criminal is pinned to the ground by a powerful dog - which makes no attempt to savage him. Shepherd dogs have the jaws for savaging. The mastiff breeds have the jaws for 'holding'. A 'holding dog' had to be brave not savage.

Like the infantry in battle, the holding dogs had the task in the medieval hunt of closing with the enemy. Close-quarter combat was their speciality. Nowadays we choose breeds because of their so-called trainability rather than their instinctive behaviour. It may save training time and therefore training funds but does it save policemen's lives when the chips are down and a life-or-death struggle between a desperate criminal and a lone policeman is being enacted? Police trainers list the qualities needed in a police dog as: soundness of temperament, courage, stamina, good health, working ability, versatility, controlled aggression, agility and fitness, drive and determination and genetic clearances. No mention is made of instinctive behaviour, the most compelling force in a dog's performance.

There are over 2,500 police-dogs in the UK, 67% are German Shepherds, with Weimaraners, Malinois, Rottweilers, Bouviers and German short-haired Pointers also featuring and interest being shown in the big Russian Black Terrier, I understand. The Bullmastiff was once the choice of Liverpool dockland police and an early breed club was a police one: The National Bullmastiff Police Dog Club, the premier organisation until 1933. What did the policemen of those times know that today's policemen do not? They had the knowledge to appreciate the breed of Bullmastiff. One policeman, Sgt Cordy, is on record in 1932 as stating: "Personally I want no better dog than a Bull Mastiff for police work, and I am ready to back it against any other breed...I will do all in my power to further this grand all-English breed." He wasn't merely being patriotic.

Colonel EH Richardson, Commandant of the War Dog School in the early part of the 20th century, selected and trained thousands of dogs in his long career. He recommended the Bullmastiff for those times: "...when a man is faced by an extremely dangerous and lonely situation at home or abroad. Absolutely undaunted in attack, and with this reputation alone carrying added value, this is a fine breed for special circumstances." Who is listening to a man with unrivalled experience of service-dogs? It is quite extraordinary that in Germany and sadly in the south-east of England too, policemen are waging war on the mastiff breeds, breeds which would offer them the greatest protection when they are under attack from violent criminals. The 'special circumstances' mentioned by Richardson refers to exactly that kind of life-or-death encounter.

Bullmastiff devotees must look for ways to employ their dogs. This is not a showy breed, rarely winning group honours at big shows and never likely to win Best-in-Show at Crufts. This is a working breed by nature and that creates the need to exercise both the minds of their owners and their admirable dogs. If you want a steadfast, unspectacular, staunch and imposing dog to guard your rural property - try the Bullmastiff!