15 THE GREAT ROUGH WATER DOGS

THE GREAT ROUGH WATER DOGS - First in the Field

by David Hancock

“THE ROUGH WATER DOG. This is a most intelligent and valuable animal. It is robustly made, and covered throughout with deep curly hair. It exceeds the water spaniel in size and strength. It is much used as a retriever by shooters of water-fowl. No dog is more easily taught to fetch and carry than this; and its memory is surprising. This variety is the Barbet, of the French, and is often called the German or French Poodle. Some are of a snowy white, others black, and others black and white.”

“THE ROUGH WATER DOG. This is a most intelligent and valuable animal. It is robustly made, and covered throughout with deep curly hair. It exceeds the water spaniel in size and strength. It is much used as a retriever by shooters of water-fowl. No dog is more easily taught to fetch and carry than this; and its memory is surprising. This variety is the Barbet, of the French, and is often called the German or French Poodle. Some are of a snowy white, others black, and others black and white.”

Foundation Stock

Those few words, in Cassell’s Popular Natural History towards the end of the 19th century, will have little meaning for today’s sportsmen. They know a great deal about the gundog breeds of today but not a great deal about the ones that went before. Yet without the water dogs, we would not have the retrieving breeds of today. Stubbs once portrayed ‘A Rough Dog’ and it is forever described by art historians inaccurately; it is a fine depiction of a rough water dog. This type of dog gave service to man the hunter long before the invention of firearms; here was the foundation stock. Their value has been overlooked in the passing of time; in The Sportsman’s Cabinet of 1803, there are nine pages devoted to them, few books on sporting dogs today even mention them.

European Need

In the ancient world anyone found guilty of killing a water dog was subject to a most severe penalty. The first written account of a Portuguese Water-dog is a monk's description in 1297 of a dying sailor being brought out of the sea by a dog with a black coat of rough long hair, cut to the first rib and with a tuft on the tip of the tail, the classic water-dog clip. Water dogs came in two types of coat: long and harsh-haired or short and curly-haired. The French Barbet displays the former, the Wetterhoun of Holland and our Curly the latter; the Portuguese Cao d'Agua or water dog features both. In Dr Caius's Of English Dogs of 1576, he described the Aquaticus, a dog for the duck, but blurs the water dog with the spaniel. He does however in 1569 provide his naturalist friend Gesner with an illustration of a Scottish Water Dog, retriever-like but with pendant ears. Writing in 1621, Gervase Markham recorded: "First, for the colour of the Water Dogge, all be it some which are curious in all things will ascribe more excellency to one colour than to another as the blacks to be the best and the hardier; the lyver hues swiftest in swimming...and his hairs in generall would be long and curled..." In 1591, Erasmus of Valvasone wrote a poem on hunting, which will appeal to Lagotto fanciers, referring to "...a rough and curly-haired breed that does not fear sun, ice, water...its head and hair resemble that of the ram, and it brings the bird back to the hunter merrily."

Function decided Type

Gundog breeds today are rightly revered and their sporting prowess as well as their breed type, which originated in function, perpetually prized. Sportsmen in early medieval times however knew the value of setting dogs and water dogs, the original retrievers, more than any of their successors. The invention of firearms did away with the need to recover arrows or bolts, as well as increasing the range at which game could be engaged. The setting dogs adapted from the net to the gun and survived, but the water dogs of Europe lost their value and many became ornamental dogs, like the Poodle. Some water dogs survive as breeds, with the Irish Water 'Spaniel' still causing discussion over whether it's a spaniel or a retriever. This type of dog, quite often black, liver or parti-coloured, had one physical feature which set it apart from most others, the texture of its coat. It is so easy when looking at a Standard Poodle in show clip to overlook their distinguished and ancient sporting history. And how many breeds recognised as gundogs can match their disease-free genotype? Anyone looking for a water retriever with instinctive skills, inherited prowess, a truly waterproof coat and freedom from faulty genes should look at the Standard Poodle, but stand by for ignorant comments from one-generation sportsmen, unaware of its heritage.

Living Examples

The Standard Poodle is a living example of the ancient waterdog whose blood is behind so many contemporary breeds: the Curly-coated Retriever, Wetterhoun of Holland, Portuguese and Spanish Waterdogs, Lagotto Romagnolo, Pudelpointer, Barbet, Irish and American Water Spaniels and the Boykin Spaniel. I suspect that the Hungarian breeds, the Puli and the Pumi, used as pastoral dogs, may, judging by their coat texture, have waterdog ancestry, as may the French breed, the Epagneul de Pont-Audemer. The Tweed Water Spaniel was behind our hugely popular Golden Retriever. The old English Water Spaniel's coat sometimes emerges in purebred English Springers.

Although our breeds of retriever were not developed until comparatively recently, the use of dogs as retrievers by sportsmen is over a thousand years old. "Traine him to fetch whatsoever you shall throw from you...anything whatsoever that is portable; then you shall use him to fetch round cogell stones, and flints, which are troublesome in a Dogges mouth, and lastly Iron, Steele, Money, and all kindes of metall, which being colde in his teeth, slippery and ill to take up, a Dogge will be loth to fetch, but you must not desist or let him taste food till he will as familiarly bring and carry them as anything else whatsoever." So advised Gervase Markham early in the seventeenth century on the subject of training a 'Water Dogge' to retrieve.

Half a century earlier, the much quoted Dr. Caius identified the curly-coated Water Dogge as "bringing our Boultes and Arrowes out of the Water, which otherwise we could hardly recover, and often they restore to us our Shaftes which we thought never to see, touch or handle again." Such water-dogs were utilised on the continent too; in The Sketch Book of Jean de Tournes, published in France in 1556, we see illustrated 'The Great Water Dogge', a big black shaggy-headed dog swimming out to retrieve a duck from a lake. This sketch could so easily have been of the contemporary Barbet, still available in France (and now here), acknowledged as an ancient type, and used to infuse many sporting breeds with desirable water-dog characteristics. The dog depicted could also represent the modern Cao de Agua, the Portuguese Water Dog. These European water-dogs are the root stock of so many modern breeds.

Ships’ Dogs

Not surprisingly such dogs were favoured by the sea-going fraternity, fishermen, sailors and traders. The dogs were trained to retrieve lines lost overboard and used as couriers between ships, in the Spanish Armada for example. In time, such dogs featured in the settlements established along the eastern sea-board of the New World by British, Portuguese, Dutch and French traders. Water-dogs exist today in those countries: the Barbet in France, the Wetterhoun in Holland, the Curly-coated Retriever and the Irish Water 'Spaniel' here and the Portuguese Water Dog there. The latter, still favoured by fishermen in the Algarve, has either a long harsh oily coat or a tighter curly coat. The Barbet has the long woolly coat, the Wetterhoun the curly coat.

Of these three, the most distinctive is the Cao de Agua, now gaining strength in this country. An ancient Portuguese breed which can be traced back to very remote times, it has great similarity with the Spanish Water Dog, now being restored to that country's list of native breeds and the Italian Water Dog, the Lagotto Romagnolo, also being resurrected. Overseas kennel clubs do, unlike ours, try to conserve their national canine heritage. There is evidence that such breeds were regarded as sacred in pre-christian times, any person killing a water-dog being subject to severe penalty. The highly individual water-dog clip led to the Romans referring to such dogs as Lion Dogs. This clip, with the bare midrift and hindquarters but featuring a plumed tail, does give a leonine appearance. The modern toy breed, the Lowchen (meaning lion-dog) displays this clip and is a member of the small Barbet or Barbichon (nowadays shortened to Bichon) group of dogs, embracing the Bolognese, the Havanese, the Maltese, the Bichon a poil frise and the Coton du Tulear.

Fishing Dogs

In his The Complete Farrier of 1815, Richard Lawrence wrote: “Along the rocky shores and dreadful declivities beyond the junction of the Tweed and the sea of Berwick, Water dogs have received an addition of strength from the experimental introductions of a cross with the Newfoundland dog…the liver-coloured is the most rapid of swimmers and the most eager in pursuit.” The genotype of the purebred Newfoundland incudes two different factors for the brown coat. Landseer Newfoundlands can be piebald red or bronze; the American vet Leon Whitney has reported both blues and reds and Clarence Little, the American coat-colour inheritance expert, has recorded the tan point pattern in pedigree Newfoundlands.

The Water ‘Spaniels’

The dark liver is the classic water dog colour, as the American and Irish Water Spaniels, the Wetterhoun and the Lagotto display today. The Wetterhoun, once famed as an otter-hunter, and the Lagotto, still famous as a truffle-finder, also feature liver and white, as our own now extinct water spaniel did. It is of interest that the Newfoundland, once described as the Great Retriever, was depicted by Ben Marshall in his well-known painting of 1811 as being black and white and covered in small tight curls. Our ancestors bred dogs with waterproof coats to support them in their ship and shoreline tasks. As the show ring now fashions so much in the pedigree dog world, it is important that judges of water dog/spaniel breeds insist on the coat texture of the entry before them is traditional and doesn’t become the subject of exaggeration. These dogs had to have a waterproof coat to survive and we should honour that heritage. Later on, in this book, I argue for the restoration of the English Water Spaniel to our list of gundog breeds.

Unfounded Grouping

The kennel clubs of the world have become seriously confused by the water dog breeds, regarding them as having different origins and functions, and therefore meriting different groupings. In Britain, our KC originally allocated the Spanish Water Dog and the Lagotto Romagnolo to the new sub-group of Utility Gundog – with the Kooikerhondje, within the Gundog Group, where they joined the Irish and American Water Spaniels. It places the Poodle in the Utility Group and the Portuguese Water Dog in the Working Group, with the Barbet, now becoming established here, awaiting allocation. From 2014 the KC originally proposed that the Spanish Water Dog, The Lagotto Romagnolo and the Koikerhondje would be reallocated to the Working Group. In late 2012 this was rescinded for the first two named. The FCI places the Water Dogs in their own sub-group, section 3 of Group 8 that embraces the retrievers and spaniels and includes the Barbet, possibly the most ancient water dog. They place the Irish and American Water Spaniels in this sub-group too. (The Poodle is grouped with the Toy breeds.) I agree with such a collection. It can however affect specialist knowledge amongst judges at shows held here and those on the continent of Europe.

The Poodle

French or German Origin

The Poodle of today came directly from the curly-coated variety of water-dog, as indeed less directly did our Curly-coated Retriever, the Wetterhoun of Holland and the surviving water spaniels. Seen nowadays as a non-sporting dog, the Poodle has a creditable sporting pedigree - the Rev Harold Browne's retrieving Poodles being much admired at the start of the 20th century. The Germans referred to such a dog as a Pudel; the French spoke of a Canne Chien or Duck Dog, which became in time Caniche, the modern French name for a poodle, whilst the Russians wrote of a Pod-laika, laika meaning a bark-pointer, like the Finnish Spitz.

I have yet to meet a French sportsman who is proud of the Poodle, but I admire them. They are clever dogs and the standard variety is underused as a gundog. Clipped to look like a Curly-coated Retriever, they look workmanlike and utilitarian, rather than exhibition items. A French shooting man, so anxious to distance his country from the Poodle, assured me that they were Russian in origin and German in development. He cited the Pudelpointer and the Schafpudel as German variations on the type. The word Pudel is German and the French do call the breed the Caniche, derived from Chien Canard or duck-dog. My French colleague insisted that the French water-dog was the Barbet and the German the Pudelhund. The corded Poodle or schnur Pudel has been dubbed the Russian Poodle. The 19th century German cynologist Dr Fitzinger listed six different varieties of the breed, but maintained that the standard version originated in north-west Africa.

The standard Poodle in a solid black coat, in a working trim, can be confused with a Barbet and even the smaller Portuguese Water Dog, just as the American and Irish Water Spaniels can appear one breed to the general public. We expect the standard Poodle to be at least 15 inches high and have a harsh textured coat, in any solid colour. The FCI expects the standard Poodle to be 17 and a half to 23 and a half inches and have a woolly coat.

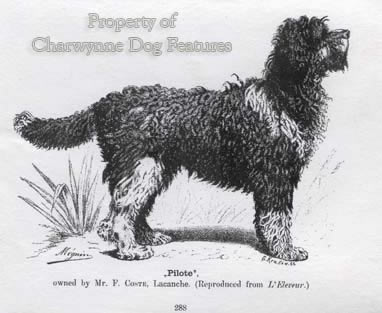

The Barbet

Changes Initiated

The advent of firearms led to many changes in the use of dogs in the hunting of feathered game. No longer were the dogs just required to bring back the valuable arrows or bolts but expected to retrieve shot game on land as well as from water. The finding of shot game on land, especially as the range of munitions increased, demanded top quality scenting powers, the persistence of a hound and the biddable qualities of a sheepdog. In due course, the breeds of land spaniel developed alongside the water spaniels, which usually had a high proportion of water-dog blood, as their coat texture revealed. The Barbet in France was one of the prototypal water dogs and after nearly becoming extinct in the 19th century, yet probably predating the Poodle, was once clever enough and versatile enough to be favoured by French poachers and continental travelling families. They were used by French fishing communities and may have contributed blood to the Newfoundland on the North-eastern American seaboard. Certainly, some of the early Newfoundlands had a distinct Barbet look to them. They are strapping dogs, powerful swimmers and clever dogs with great energy. It would be good to see them being used by wildfowlers, they are well-equipped to be really good water retrievers.

The Irish Dog

The Irish Water Spaniel, affectionately known as the whiptail, is a rich dark liver-coloured gundog, with a coat of crisp tight ringlets, free of any wooliness, but containing the natural oiliness of the water dog group of dogs. Just under two feet high, strongly made but compactly built, the breed is shown here as a spaniel but enters field trials as a retriever, yet another sign of the KC’s misunderstanding of water dogs. In his The Dogs of the British Islands of 1878, ‘Stonehenge’ gives the view that this is the by far the most useful dog for wildfowl shooting at present in existence and quotes a breeder called Lindoe as stating “Notwithstanding their natural impetuosity of disposition, these spaniels, if properly trained, are the most tractable and obedient of all dogs, and possess in a marked degree the invaluable qualities of never giving up or giving in.” That sums up the character and potential of the ‘wild Irishman’, with highly experienced sportsman, James Wentworth Day, in his The Dog in Sport of 1938, describing him as ‘one of the finest water-dogs in the world…the best dog out of Ireland for the all-round shooting man.’ Their blood is valued by wildfowlers too. In The Countryman’s Weekly of the 21st of March, 2012, Derek Robinson described how his Labrador cross Whiptail performed in the field: “The hunting ability and nose is far better than any Lab while his coat is dense and coarse, drying so much quicker than a spaniel’s. It is wildfowling that he’s been trained for…” Never over-popular, their annual registrations with our KC averaging just over 100 a year, it would be good to see their Grouping as a gundog breed rethought and their recognition as a rather special breed assured.

The American Dog

The American dog has a distinct look of the Irish dog about it but unlike the other types of water dog is scarcely known here. Only 15-18 inches high, solid liver, brown or dark chocolate, their coats can range from the close curl of the water dogs to the marcelled coats of the water spaniels. Long used as a wildfowlers’ dog, American sportsman and writer, Freeman Lloyd, in his All Spaniels of 1930, stating that: “There was a fine old breed or strain of liver-colored water spaniels of the flat or wavy-coated variety which was much in use in several parts of the United States and Canada. There were others with curly coats and often long tails, more or less related to the water spaniels of Ireland. Here was a spaniel strong enough for anything…” As with the Cocker Spaniel and the Staffordshire Bull Terrier, the Americans have stabilized their own type and established new breeds of dog, if mainly in the show world. The American Water Spaniel has recently been imported here but it will need immense efforts to get it established.

The Portuguese Dog

This ancient Portuguese breed, recognized by our KC, not as a gundog, but as a ‘Working Dog’ in the Group for such dogs, can be black, white, shades of brown and parti-coloured, with two distinct types of coat: long and loosely waved or short, dense, fairly harsh and curly; it’s around 20 inches high, weighing around 45lbs. They are usually given the classic water dog clip from the last rib. Now well-known here, with around 100 registered a year, it would be good to see the curly-coated variety used by wildfowlers and their latent sporting instincts encouraged.

The Spanish Dog

This water dog breed is recognised by our KC as a gundog and was first seen here in the 1970s. When I was based in Gibraltar half a century ago and visited Spanish ports at the southern end of that country, you could find dogs of this type as all-purpose dogs there and even as herding dogs further inland. Around 18 inches high, in the same coat colours as the Portuguese dog, they can be naturally bob-tailed, have a woolly curled coat, even corded, but are not given the classic water dog clip. They are justifiably becoming quite popular here as a companion dog, with nearly 200 registered with the KC in 2011, but I have not heard of their employment as a gundog in Britain, despite their correct Grouping.

The Italian Dog

This breed, known as the Lagotto Romagnolo, and used there as a duck retriever and as a truffle hound, is the same size as the Spanish dog but comes in a wider range of colours. Originally, a water retriever from the lowlands of Comacchio and the swamps of Ravenna, this breed moved on to become a valuable truffle locating dog in the plains and hills of Romagna, being recognized as a breed internationally in 1995. Its coat can range in colour from solid white to parti-coloured white and brown or orange or roan. Its texture is curly, dense, woolly and in ringlet form. Recognised here as a gundog breed, 35 were registered in 2011 and I can see this attractive breed steadily increasing its popularity.

The Dutch Dog

The Frisian Water Dog is of a type found all over Europe in past times, including Britain. Our English Water Spaniel, once listed by the Kennel Club, now lost to us, but easily restored if ever we regain our national pride, was in this mould. The Portuguese, the Spanish, the Italians, the French and the Americans have retained and treasured their water-dogs; we have, in our reckless pursuit of all things foreign, forsaken ours. The Dutch too have conserved their ancient breed, the Frisian Water Dog, or Wetterhoun, is a curly-coated, solid black or brown or part-coloured two-foot high dog, rather like a smaller Curly-coated Retriever. As their name suggests they excel in water, and are robust working dogs, rather than ornamental pets. As a breed they are not recognized in Britain but exhibited at European and World Dog Shows.

The Water Dog Legacy

Distinctive Coats

I have seen pure-bred Labradors featuring a tightly-curled coat and we have all seen English Springer Spaniels with very curly coats. I suspect the linty coat of the distinctive Bedlington Terrier owes its origin to water-dog blood, perhaps that of the Tweed Water Spaniel, once known in the area where the Bedlington was developed. The early Airedale Terriers, bred originally as waterside terriers in the Aire valley, had noticeably curly coats; this is now frowned on, the word crinkle-coated being preferred. The now extinct Llanidloes Setter featured this tight, densely-curled, waterproof coat. The Tweed Water Spaniel blood in the Golden Retriever is however not only acknowledged but prized. Our ancestors knew the value of water-dog blood.

It may not suit the misplaced pride of the shooting man of today to acknowledge the blood of poodle-like dogs in his working gundogs or associate such dogs with his sporting image. I see it as a matter of gratitude more than anything else. It may be difficult to accept a shared origin between a strapping Curly and a toy Poodle, a sturdy Wetterhoun and a diminutive bichon and a lion-clipped tiny Lowchen and a whiptail. But, as the Chihuahua and the Great Dane dramatically illustrate, different purpose has led to different development; ornamental dogs are expected to be small, retrievers have to have substance and stamina.

The liver and the black coat colours of the ancient water-dogs and their unique curly texture have survived and surfaced in many of today's breeds, whether sporting or non-sporting in use. Their fondness for and durability in water lives on too, whether the breed is linked to Ireland or Holland, Italy or Spain, France or Portugal, America or Britain. Water-dogs are the rootstock of many of our sporting breeds whether they have lost or retained the typical coat texture and colours of their distant ancestors. The water-dogs of Europe have contributed a great deal to our sporting heritage and more should be made of the debt we owe them, in breed histories for example. May those of Italy and Spain, now saved from extinction, go from strength to strength. And how about recreating our Tweed Water Spaniel?

“…this very description of water-dog differs materially in size, as well as in the length and rigid elasticity of the coat, from the smaller and more delicate, as well as more domesticated breed under the denomination of the water-spaniel, it becomes only necessary to recite such distinguishing traits of his utility as are but little known to that part of the sporting world who are situate in the centrical and inland parts of the kingdom. Upon the sea-coast, the breed is principally propagated, where they are mostly brought into use, and held in the highest proportional estimation; but along the rocky shores, and dreadful declivities, beyond the junction of the Tweed with the sea at Berwick, the breed has derived an addition of strength from the experimental introduction of a cross with the Newfoundland dog, which has rendered them only adequate to the arduous difficulties and diurnal perils in which they are systematically engaged.”

From The Sportsman’s Cabinet of 1803