10 THE CHESAPEAKE BAY RETRIEVER

THE CHESAPEAKE BAY RETRIEVER

by David Hancock

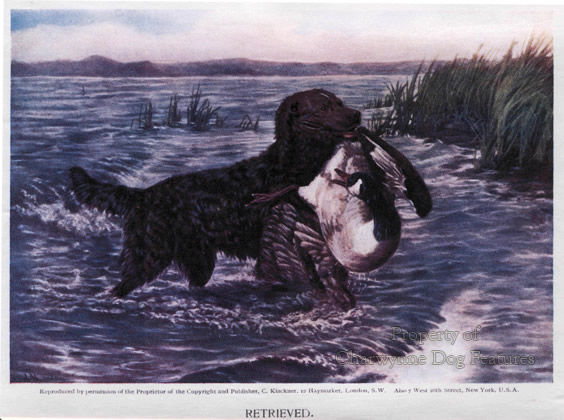

The renowned Norfolk sportsman James Wentworth Day greatly admired the character of the Chesapeake Bay Retriever, as these words from his The Dog in Sport of 1938, illustrate: “Their impression of power is quite remarkable. They give one the feeling of immense resources of energy, of great reservoirs of knowledge, of tolerance of disposition, obstinacy of purpose, and tenacity of principle. They are responsive, and they have a lot of quiet good sense.” They would certainly be my first choice as a wild-fowling companion. In his Dog Breaking of 1915, 'Wildfowler', a much respected gundog authority, spelled out the requirements for a successful wildfowling dog: “...the dog has to learn so many more things than other breeds of dogs. He must stay ready for flighting, remain still in a punt, he must never open under the strongest temptation, never jump up, never be excited, obey signs implicitly, hunt when told and keep to heel when ordered...be tender-mouthed, very keen-nosed, strong- constitutioned, plucky, swim for ever, and stand hard winters with equanimity. A dog who does all these things well clearly is a valuable dog.” Clearly! List the dogs you would prefer not to share a punt with!

The renowned Norfolk sportsman James Wentworth Day greatly admired the character of the Chesapeake Bay Retriever, as these words from his The Dog in Sport of 1938, illustrate: “Their impression of power is quite remarkable. They give one the feeling of immense resources of energy, of great reservoirs of knowledge, of tolerance of disposition, obstinacy of purpose, and tenacity of principle. They are responsive, and they have a lot of quiet good sense.” They would certainly be my first choice as a wild-fowling companion. In his Dog Breaking of 1915, 'Wildfowler', a much respected gundog authority, spelled out the requirements for a successful wildfowling dog: “...the dog has to learn so many more things than other breeds of dogs. He must stay ready for flighting, remain still in a punt, he must never open under the strongest temptation, never jump up, never be excited, obey signs implicitly, hunt when told and keep to heel when ordered...be tender-mouthed, very keen-nosed, strong- constitutioned, plucky, swim for ever, and stand hard winters with equanimity. A dog who does all these things well clearly is a valuable dog.” Clearly! List the dogs you would prefer not to share a punt with!

Origins: Link with Norfolk

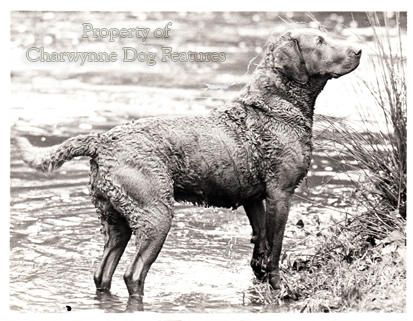

In his book British Dogs of 1888, Hugh Dalziel, kennel editor of The Country Magazine, exhibitor and judge, produced a chapter on the Norfolk Retriever. He largely relied on the knowledge of 'Saxon', a Norfolk sportsman, who provided the text. Dalziel acknowledged that "although Retrievers answering this description may be more plentiful in Norfolk than elsewhere, they are met with often enough in all parts of the country." 'Saxon' describes the coat colour of this retriever as: " ...more often brown than black, and the shade of brown rather light than dark -- a sort of sandy brown, in fact." He goes on to describe the coat as looking 'rusty', inclined to be coarse, feeling harsh to the touch, curly but not as close and crisp as in the Curly-coated Retriever of the show ring, tending to be open and woolly. He describes a saddle of straight short hair across the back. Gamekeepers usually docked their tails which made them appear to some sporting writers as spaniels, despite their stature.

...more often brown than black, and the shade of brown rather light than dark -- a sort of sandy brown, in fact." He goes on to describe the coat as looking 'rusty', inclined to be coarse, feeling harsh to the touch, curly but not as close and crisp as in the Curly-coated Retriever of the show ring, tending to be open and woolly. He describes a saddle of straight short hair across the back. Gamekeepers usually docked their tails which made them appear to some sporting writers as spaniels, despite their stature.

These dogs were the wildfowlers' retrievers, used "on broad, river, sea-coast and estuary". It was alleged that the Pointer was not hard enough for such work, the water spaniel too impetuous but the Norfolk Retriever "will face a rough sea well, and they are strong swimmers, persevering, and not easily daunted in their search for a dead or wounded fowl." 'Saxon' claims that Norfolk was outside 'the magic circle of shows' and so the 'improvement' of them has not taken place. He makes it quite clear that this Norfolk dog is different from a spaniel (and appreciably larger) and from the Curly-coated, Flat-coated and Labrador Retrievers. The occasional long coat crops up in Chessie litters, causing discussion on origin, but coat variations can occur in most gundog breeds, illustrating a mixed origin not a pure one and that’s good.

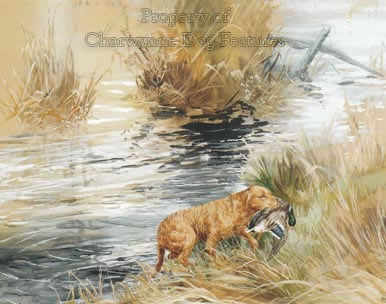

If you tried to find the contemporary retriever breed to fit closest to the description of the Norfolk Retriever, then the Chesapeake Bay Retriever would be my choice. The breed standard of the latter describes the coat as "harsh...hairs having a tendency to wave on neck, shoulders, back and loins...straw/bracken coloured, red-gold (sedge) or any shade of brown...White spots on chest, toes and belly permissible. The smaller the spot the better." The Norfolk Retriever featured white in the form of a spot on the chest. 'Saxon' stated that the most distinctive features of the Norfolk Retriever were its unique coat and its quite remarkable hardiness. The first sentence of the Chesapeake's standard mentions its distinctive coat and lists one of its characteristics as courageous with a great love of water.

Newfoundland Links

Some authorities have claimed that the Chesapeake Bay Retriever was developed from two ship-wrecked so-called ‘Newfoundlands’ (one black, one red, which were never mated together; the red one only threw blacks) and others from 'Red Winchester' water-dogs out of Ireland. The American writer, Bede Maxwell, in her forthright The Truth about Sporting Dogs of 1972, thought this link might be with a fisheries patrol vessel HMS Winchester which sailed out of Cork to the eastern American seaboard, with officers taking their Irish Water Spaniels with them. But Newfoundlands and Irish Water Spaniels have distinct anatomical differences from Chesapeakes. And, just as I suspect that the Nova Scotia Duck-tolling Retriever was taken to Canada as the red decoy dog of England, especially from the East Anglia part of England, so too could the Norfolk Retriever. Perhaps some diligent breed researcher could look at the records in Norfolk, Virginia, at the entrance to Chesapeake Bay itself.

If my theory is correct then the great sporting county of Norfolk has missed out in several ways concerning the titles of sporting gundogs. For just as the Norfolk Retriever could be behind the Chesapeake Bay Retriever and renamed in its new country, so too could the English Springer Spaniel have been named the Norfolk Spaniel and the Nova Scotia Duck-tolling Retriever called the Red Norfolk Decoy Dog. In Britain, we respected the backgrounds of both the Newfoundland, which could so easily have become the Landseer Retriever, and the Labrador, which could so easily have become the Malmsbury Retriever, from its early development in England. We lost our Tweed Water Spaniel and English Water Spaniel; the Americans still have their Boykin Spaniel and American Water Spaniel.

In his The Illustrated Book of the Dog of 1880, Vero Shaw felt obliged to mention the Norfolk Retriever and wrote that: "It is claimed for this breed...that it is peculiarly adapted for the pursuit of wild birds in the low-lying districts of Norfolk, and that few, if any other varieties of dog, could be found to endure the hard work equally well." In his Breaking and Training Dogs of 1910, 'Pathfinder' wrote of retrievers: "...I have known livers in Norfolk dignified with that prefix, just as it was usual at one time to speak of the English Springer when met there as the Norfolk Spaniel." In his The Sporting Dog, published in New York in 1904, the American writer, Joseph A Graham, stated that: "The Chesapeake is not so peculiar or distinct. In fact, he is of rather common appearance. Stout and strong, sedge or rusty brown in color, the coat dense and close, he is not a beauty."

So we have a rusty-coloured, broken-coated, retriever-sized dog in Norfolk, England and subsequently an identical dog near Norfolk, Virginia, at the mouth of Chesapeake Bay. The dog in England is not recognised as a breed, Vero Shaw hinting that it was too nondescript for that to happen. Joseph Graham describes the dog in America as 'of rather common appearance' but it becomes recognised as a breed nevertheless. In his The Dog of 1880, the respected 'Idstone' wrote "Liver and sandy Retrievers have a few partisans. They are the sort which 'always were kept', people tell you, 'in our family'...I know of no family priding itself on this coloured species just now, but I have heard that they are not uncommon in Norfolk." It may be far too late to have the Labrador renamed the Devon Retriever. But how worthwhile a venture it would be to find rusty-coloured, broken-coated retrievers 'not uncommon in Norfolk', however nondescript, once again recognized, and this time registered, as a Norfolk gundog breed. Abroad or at home, it is so encouraging to learn of the Penrose and Arnac Bay dogs doing well in the field, with Penrose Jack Tar a full champion in the UK and Sweden and Penrose Nomad and Arnac Bay Winota becoming the first full champions in both the UK and Eire.

I think back to the worries of Wentworth Day on the Chesapeake: "It will take many generations of stupid women in Bayswater and suede-footed young men in Kensington to ruin the character of this eminently sensible working dog. He has all the dignity, the native aristocracy, the quiet good sense and the instinctive judgement of the British working man...If you have two or three Chesapeakes in the kennel there will never be any disturbances in your shooting routine --none of that hoity-toity flightiness of the Gordon Setter, the kiss-me-quick slobberings of the spaniel or the mental whimperings of the Golden Retriever. Do not imagine for a moment that I dislike any of these three excellent breeds of sporting dog. But I mourn for individuals among them. The show-bench and the drawing-room have made fools of them...I doubt if you could ever do that with the Chesapeake. He will probably bite someone finally, just as a protest and then walk out of the house, a dog in search of a man for a master." This strongly-worded tribute to the Chesapeake Bay Retriever may not appeal to everyone but the sentiments apply to all the retriever breeds and should be heeded by all who love their particular breed and care about their spiritual happiness and well-being.