989 RUSSIA'S CANINE HERITAGE

RUSSIA'S CANINE HERITAGE

by David Hancock

An acquaintance of mine, of Russian descent, claims that dogs in Russia represent social circumstances there very aptly. He sees the Moscow Guard Dog, allegedly developed to protect gangsters, and the Moscow Toy Terrier, specially bred to fill the hand-bags of the nouveau riche, as reflecting current times. This, he says, contrasts markedly with the truly glamorous Borzois of the Tsars and the stylish Samoyeds in the gracious drawing rooms of the old regime, where canine handsomeness was prized. He may have a point about his former country's canine heritage, but it was under a doctrinaire regime there where the Russian Black Terrier was created as a service dog by geneticists whilst we, in the West were still recycling old and worn genes entirely on false expectations of the benefits of breed purity. I'd prefer the Samoyed to be patronised as a working sled-dog and the Borzoi to be used as a sighthound but I mourn the apparent loss of their scenthound breeds.

The Russians still have their Harlequin Hound, linked by many with the Harlequin Great Dane. The Moscow Society of Hunters and Fishermen stage an annual exhibition, attracting over a thousand dogs. There you can see Russian Hounds (a breed similar to the Finnish Hound and the Estonian Hound), Russian Skewbald or Piebald Hounds and the Harlequin. I understand that the Dynamo Sport Society of Tula developed a uniform, high quality pack of 'Harls' for use on wolf, leading to these dogs being used to upgrade stock elsewhere in Russia. As the geneticists Little and Jones have shown, the harlequin white is dominant over solid colours, i.e. tan, black, etc but the factor can have a semi-lethal dimension, different again from that of the Dunker Hound's. The Russian scenthounds were used with the Borzoi in the wolf hunt. A giant bear hound, the Mendelan, was once favoured but despite its distinct type faded from view and was lost to us. In his book The Dog in Sport of1938, James Wentworth Day records: “…the great Mendelans owned by the late Tsar of Russia and kept by him at the summer palace at Gatchina…were the size of a calf, and…were used for rousing bears out of thickets in summer and from their hibernating quarters in snow in winter.” I don’t believe that the rough-coated so-called Russian or Siberian Bloodhound has survived the endless upheavals of Russian society in the 20th century. It was interesting to note that at the 1998 Moscow Dog Show as many as 70 Bloodhounds were entered, 28 in the Working Class; I believe they are used to flush game.

In the pastoral dog world, the Russians use the Laika breeds as all-round farm dogs and they work on a variety of stock, as well as general purpose hunting dogs. They have to be versatile. In Ireland, I’ve seen the Kerry Blue and Wheaten Terriers used as multi-purpose farm dogs, able to undertake just about every canine role on the farm. Farmers overseas needed small dogs too; to control pests such as rats, to act as turnspit dogs in the farmhouse kitchen and to go to ground when foxes were hunted. In Germany the Schnauzer varieties provided the range of canine skills around the farm. In Russia, their Laika breeds offered a similar versatility, the large ones acting as herders and the small ones as yard dogs and ratters. All over the world, dogs, whether employed to drive cattle, sheep, goats or reindeer, to guard farmsteads or flocks, to kill foxes or rats or 'hold' an individual animal were bred with just one object in mind: their function. And, the pastoral breeds above all, had challenging roles to perform; in Russia the wolf threatened livestock of all kinds, especially on the steppes where the livestock protecting types more than earned their keep.

.jpg)

The more eye-catching flock guardians there - their owtcharka breeds, provide the strong link with the timeless pastoral ways. Each breed typifies the conditions where they are employed. The Central Asian Owtcharka needs less coat but all the other attributes to do its work. The breed is found from the east of the Urals to areas of Siberia and south into Mongolia. The best examples today tend to be in Turkmenistan, where it has been recognised as 'a national treasure'; they can also be encountered in Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan and Tajikistan. Their coats are shorter, but their skin is thicker than the other owtcharka breeds, and their ears and tails are normally cropped. They remind me of a smooth St Bernard. They resemble too the bigger forms of shepherd's dog once depicted here, when used in times past as a shepherd's mastiff or flock guardian. The Central Asian is a powerful breed, having been used as a hunting dog on boar and bear because of its bravery and dash. Those with tan markings over their eyebrows have been dubbed the 'four eyed Mongolian Dogs'.

The third owcharka breed is the South Russian, white, off-white or grey, long-haired, over 30 inches at the shoulder and weighing around 75 kgs. They remind me a little of the early depictions of our Old English Sheepdog, as portrayed by Reinagle for example. They are similar to the Hungarian Komondor, without that coat texture, being used, like the latter, on the steppes, only in their case in the Ukraine. This south Russian breed is not one to be trifled with; it is known as 'the white giant' in some areas of its homeland and is often harshly treated. There is an old Russian saying that states that a 'pampered South Russian is a killer'! The military have found uses for them but their export is not encouraged. Despite their reputation for 'hair-trigger aggression', you have to admire a breed that can survive such a hard climate, such fearsome predators and stern handlers, over many centuries. Their aggression may prevent their becoming household pets but understandably they are widely used as house-guards. But without question, Russia's great gift to the canine world is their wolfhound, the world-famous Borzoi.

Behind the modern single breed of Russian Borzoi, there are barrel-chested Caucasian Borzoi, huge curly-haired Courtland Borzoi and bigger-boned Crimean dogs. This type was found as far west as Albania too. The Kennel Club Borzoi is now confined by a closed gene pool, in the rigid pursuit of purity rather than performance, but the lesser known Borzoi types are really South Russian lurchers both in employment and in breeding method. Hungry peasants and level-headed kulaks didn't keep hounds because they were pretty! Although the Russian wolfhound is known to kennel clubs around the world as the Borzoi, the word itself means light, swift and agile, being used rather loosely just as greyhound was in Britain, levrier in France and windhund in Germany. The Borzoi was more commonly used for fox and hare coursing and the Russians once referred to Asiatic, Polish (Chart or Chort), Crimean or Tartar Borzoi (these more like Salukis) and the Circassian variety too. The Scottish Greyhound (Deerhound) was used on wolves and other quarry, coursing hounds having long been used in a wide variety of pursuits. It is easy to forget when looking at contemporary breeds that their ancestors did not breed true to type, being judged solely on performance, not on conformation to a set standard.

The graceful athletic build of the Russian wolfhound has long drawn widespread admiration: Charles Darwin described them as an 'embodiment of symmetry and beauty'. Undoubtedly the attractive silky coat of the modern pedigree Borzoi enhances its physical appearance. But as with the Saluki and the Ibizan hound, of this type of swift hound, there were varieties of coat in the Borzoi too. The Hunter's Calendar and Reference Book, published in Moscow in 1892, divided the Borzoi into four groups. First, Russian or Psovoy Borzoi, more or less long-coated; second, Asiatic, with pendant ears; third, Hortoy, smooth-coated and fourth, the Brudastoy, stiff-coated or wire-haired. But whether the hounds were sleek or bristle-haired, wolf coursing in Russia before the Revolution was what fox-hunting was to Britain and par force hunting was to France.

As Leo Tolstoi recorded in War and Peace: "Fifty-four coursing hounds were taken with six mounted horsemen and keepers of hounds. Apart from the Master and his guests, another eight huntsmen took part, with more than forty hounds. In the end, there were one hundred and thirty hounds and twenty horsemen in the field." Tsar Peter II kept a pack consisting of 200 coursing hounds and over 420 Greyhounds. Prince Somzonov of Smolensk had 1,000 hounds at his hunting box, calling himself Russia's Prime Huntsman. Better known was the hunt with the Perchino hounds near Tula on the river Upa, where Archduke Nicolai Nikolsevich established a hunting box in 1887 and hunted two packs of 120 par force hounds, 120 to 150 Borzoi and 15 English Greyhounds. To ensure sufficient hardiness for winter wolf hunts, both horses and hounds were kept in unheated stables or kennels.

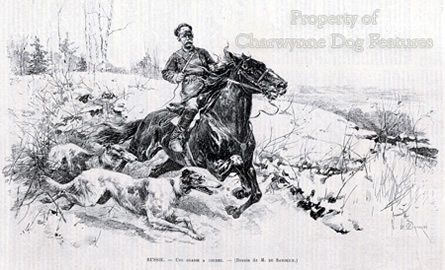

Hunting from sledges sometimes took place from October, with mounted beaters putting up the wolves, which were often fed to keep them in the hunting grounds. In the Perchino game reserve, between 1887 and 1913, 681 wolves were killed, as well as 743 foxes, 4,630 brown hares and 4,026 white hares; Borzois obtaining the bulk of this bag. Whatever the rights and wrongs of hunting on such a scale, the robustness, fitness and stamina of the hounds must have been remarkable. Coursing with Borzois in Tsarist Russia called for a high standard of horsemanship and superbly-trained hounds. Each mounted handler rode with his three hounds on long leashes, slipping the hounds whenever a wolf was either put up by the extended line of mounted beaters or flushed out of the woods by scent hounds of the Gontchaja type. Many of us would find it difficult enough to control three Borzois on short leashes whilst dismounted!

When I study Borzois, whether at World Dog Shows or Championship events in Britain, I recall the first depictions of the breed in western Europe, less furnished with leg and tail hair, much more workmanlike but still physically appealing. Many of them came from the famous hunting kennels of Russia only a generation or so previously. The owcharka breeds I saw at the World Dog Shows held in Helsinki, Vienna and Budapest still had that strong protective 'edge' to them. The latter will need to be watched carefully as these breeds become favoured as pets. I have seen portrayals of 'Russian Poodles' in art and read of Russian Setters in mid-19th century England but doubt if they have survived the Soviet times. The canine heritage of a country can tell you a great deal about that land - its social times in particular. Russia's surviving breeds of dog, especially the increasingly-ornamental Borzoi and Samoyed, deserve our interest and our perpetuation of them but surely only in their true mould.