966 PULLING POWER - the draught dogs

PULLING POWER - THE APPEAL OF THE DRAUGHT DOGS

by David Hancock

It's unjust in many ways for haulage dogs to be remembered solely through demonstration-carts at shows or in snow-sports or cross-country events in northern countries. The service to man of dogs that could haul laden carts and sledges in town streets or arctic conditions was considerable. We perpetuate baiting dogs but not carting dogs. In Europe the strapping cart-hauling dogs were mainly crossbred and so unlikely to be restored as a lost breed might be. They weren't prized for the pureness of their blood but for their pulling power. In Eastern Russia and North America, on both sides of the Bering Straits, primitive people benefitted when determined strongly-made dogs transported their goods over unforgiving terrain. Unlike the lost cart-dogs we still have the Samoyeds and the husky breeds to perpetuate the sled-dogs. Long forgotten are the dogs used to pull stretcher-carts in the Great War or haul agricultural machinery used to work the land or those used by primitive people in North America to pull loads strapped to long poles and dragged along the ground. This wasn't merely a test of physical power but a test of will - sheer determination, rather as pulling contests for Staffies are sometimes held.

It's unjust in many ways for haulage dogs to be remembered solely through demonstration-carts at shows or in snow-sports or cross-country events in northern countries. The service to man of dogs that could haul laden carts and sledges in town streets or arctic conditions was considerable. We perpetuate baiting dogs but not carting dogs. In Europe the strapping cart-hauling dogs were mainly crossbred and so unlikely to be restored as a lost breed might be. They weren't prized for the pureness of their blood but for their pulling power. In Eastern Russia and North America, on both sides of the Bering Straits, primitive people benefitted when determined strongly-made dogs transported their goods over unforgiving terrain. Unlike the lost cart-dogs we still have the Samoyeds and the husky breeds to perpetuate the sled-dogs. Long forgotten are the dogs used to pull stretcher-carts in the Great War or haul agricultural machinery used to work the land or those used by primitive people in North America to pull loads strapped to long poles and dragged along the ground. This wasn't merely a test of physical power but a test of will - sheer determination, rather as pulling contests for Staffies are sometimes held.

To this day on the continent of Europe, dogs are still used to pull carts, as the Bernese Mountain Dog fanciers sometimes demonstrate at their shows in Britain. Just over a century ago, Professor Reul, one of the founders of the Belgian Club for Draught Dogs, wrote: "The dog in harness renders such precious services to the people, to small traders and to the small industrials (agriculturists included) in Belgium that never will any public authority dare to suppress its current use." Taplin, writing in The Sportsman's Cabinet of 1804 on Dutch dogs, stated that: "...there is not an idle dog of any size to be seen in the whole of the seven provinces. You see them in harness at all parts of The Hague, as well as in other towns, tugging at barrows and little carts, with their tongues nearly sweeping the ground, and their poor palpitating hearts almost beating through their sides; frequently three, four five, and sometimes six abreast, drawing men and merchandize with the speed of little horses." In Britain too, draught dogs were widely used, until, because of the huge increase of traffic in London, compounded by the widespread ill-treatment of the dogs, led to this practice being forbidden by law.

Dogs were used instead of ponies to pull the carriages of some eccentric sportsmen in the 19th century. In Lawrence's The Sporting Repository of 1820 there is reference to a man who "exhibited a carriage drawn by six dogs. These were the largest and most powerful which we have ever witnessed." Another man boasted of the pulling feats of his 'Siberian Wolf-dog', which pulled a dog-cart unaided. In Shropshire, Squire Danville Poole used a pack of black and tan terriers to keep the local curs away from his horse-drawn carriage. I could imagine many of the working terriers I see at country shows relishing such a task. Many of the large powerful draught-dogs in the Low Countries descended from "matins", once used as boar-lurchers in the hunt. These determined coarsely-bred dogs were used at the kill, so as not to risk the more valuable boarhounds on the boar's tusks. The wild boar is a formidable quarry, with many dogs being killed in their hunting. As boar-hunting lapsed, largely because of the scale of slaughter by reckless hunters, a new employment was found for such strong willing dogs, in the commercial dog-cart market. The Matin Belge, a distinct if unrecognized type, is being restored by a devoted group of fanciers, inspired by the admirable Alfons Bertels and supported by Johan Gallant, at the present time.

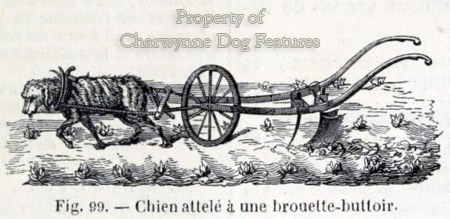

Less glamorous but even more useful were the crossbred draught dogs, using their more than useful pulling power. The 'Trekhond' in Holland, the 'Ziehhund' in Germany and the 'Chien de Trait' in France became the small work-horses of Western Europe. Bylandt in his Dogs of all Nations of 1904 described such dogs as being: from 26 to 31½ inches in height at the shoulder, weighing a minimum of 112lbs for the dogs and 100lbs for the bitches, rather short-muzzled, with docked tails and usually fawn or brindle with a black mask. These are the colour combinations of the mastiff breeds, which manifested themselves in the matins, a type of dog rather than a breed. The matins were usually the 'disposable' dogs of the boar-hunts.

In the countries where draught-dogs were once utilised, the local authorities regulated their use. In Belgium it was not permitted to: harness dogs smaller than 24" at the shoulder, use old or sick dogs, bitches in whelp or still suckling, harness a dog with another animal, allow the dog to be controlled by someone under 14 years old, convey passengers or leave harnessed dogs in the sun in hot weather. The traces had to be at least a yard long and the collar and any harness in contact with the dog had to be padded. Any vehicle towed by dogs had to have springs and be fitted with brakes. A single dog could only pull 300lbs and two or more dogs 400lbs, including the vehicle's weight. Traders in sled dogs made comparable judgements from their experiences. They learned to value economy of motion in their dogs; their gait leading to success, a smooth motion in which their feet hardly leave the ground. The top racing teams cover a mile in just over 3 minutes nowadays. This capability is rooted in the size-to-weight ratio. The dogs pull by pushing forward and the heavier the dog the greater the energy required to do so. A 50lb Alaskan hybrid husky has evolved as the optimum sled dog. Of course such a dog has to have the right feet, coat and constitution to support its work, but the relationship between height and weight is the key. I have seen Malamutes on the move with an ease of motion that is truly impressive in its sheer effortlessness or economy of movement.

The Swiss made most use of the Great Swiss Mountain Dog, now being seen in Britain, and the Bernese Mountain Dog, now rightly a firm favourite here. In Brussels and Antwerp a century ago, a good draught-dog could be bought for the equivalent of £4. The dogs were fed on a mixture of stale bread and horsemeat. Some enthusiasts would course their dogs over two or three miles, with the public able to place wagers on each contestant. In Portugal and Spain dog-carts were utilised to deliver the casks of grapes from the vineyards and the cork from the forests. The dogs used resembled today's Estrela Mountain Dog in Portugal and the Spanish Mastiff in Spain.

Draught dogs were not only cheaper to employ than horses but were much more manoeuvrable. Importantly too, their drivers were not required to pay tolls. Despite this, the use of dog-carts was never widespread in Scotland, perhaps because of the long distances between towns. When the railways came, dog-drawn carts were used in the south of England to carry fish from the ports to the railheads. Some made the journey from Brighton to Portsmouth in one day, returning the following day. Humanitarians argued that dogs' paws were never designed to cope with hard sharp-stoned roads, whatever their widespread and indispensable use over snow in Arctic countries.

Some critics suggested that dog-carts frightened horses and vets even cited such use as a means of spreading rabies! The use of dog-carts in England was ended by piecemeal legislation. In 1839 a clause in the Metropolitan Police Act denied the use of dogs as beasts of burden within 15 miles of Charing Cross. This alone resulted in the destruction of more than 3,000 dogs. When an anti-dog cart bill was being introduced in 1854, the Earl of Malmesbury stated that in Hampshire and Sussex alone there were 1,500 people earning a living from dog-carts. In the debate, Lord Brougham spoke of a dog-cart driver who had ripped up an exhausted dog and given its entrails to two other dogs for food. The Earl of Eglington, opposing the bill, forecast the destruction of between 20,000 and 30,000 dogs. The Bishop of Oxford stated that ill-used dogs had been traced for distances of up to 20 miles by following blood trails on the highway. He claimed that it was not unusual for a dog to be driven 40 or 50 miles on a hard road until it could just not continue, when it would be destroyed and replaced by a fresh dog. The bill went through.

Some of the breeds used abroad as draught dogs became recognised and are still with us. The Swiss breeds are probably the best known, with even the St Bernard finding employment in this way. The Newfoundland was utilised in its home country to pull fish-carts, while Dogue de Bordeaux crosses were employed as cart-dogs in the south of France. The Leonberger, the Rottweiler and even the German Shepherd Dog, have all been used too in this way. Perhaps the greatest pleasure enjoyed by dogs is that of being employed, being useful to their owners, being exercised with a mission. I am not advocating a return to dog-carts, there would be a risk of cruelty from some owners. It would be satisfying to see working tests for big dogs, designed to test their strength and application, but also to employ them, help them to feel useful, develop their spirit and counter the sheer boredom of most of the daily lives. Dogs desperately want to serve us! Perhaps too we could employ them much more compassionately than their 19th century owners did - relishing dog's enjoyment of working for and with us.