944 GET SHORTY - THE PAIN OF SHORT AND BENT-LEGS IN DOGS

GET SHORTY! THE PAIN OF SHORT CROOKED LEGS

by David Hancock

Dogs with short crooked legs have long been a feature of man's association with sporting, working and companion dogs. Breeds with crooked and particularly short legs, like the Dachshund, the two corgi breeds and other heelers, the various Basset Hound breeds, a number of terriers and many Toy dog breeds, have been favoured for quite some time by any number of people. There is a worry however that in those breeds both the crookedness and the shortness of the legs has been more and more exaggerated and not to the benefit of the dog. Some breeders of such dogs have declared resentment of measures being planned on mainland Europe to counteract extreme shortness in a dog's legs, pleading that their particular breed has 'always looked like that' and is not discomforted in such a way. There is of course a huge difference between small dogs with proportionately short legs and bigger dogs made appreciably shorter by the absence of leg length.

Dogs with short crooked legs have long been a feature of man's association with sporting, working and companion dogs. Breeds with crooked and particularly short legs, like the Dachshund, the two corgi breeds and other heelers, the various Basset Hound breeds, a number of terriers and many Toy dog breeds, have been favoured for quite some time by any number of people. There is a worry however that in those breeds both the crookedness and the shortness of the legs has been more and more exaggerated and not to the benefit of the dog. Some breeders of such dogs have declared resentment of measures being planned on mainland Europe to counteract extreme shortness in a dog's legs, pleading that their particular breed has 'always looked like that' and is not discomforted in such a way. There is of course a huge difference between small dogs with proportionately short legs and bigger dogs made appreciably shorter by the absence of leg length.

The European Convention for the Protection of Pet Animals (ETS 125), adopted by multilateral consultation on March the 10th 1995, covers two aspects of canine shortleggedness. The resolution sets out guidelines for 'maximum values for the proportion between length and height of short-legged dogs (e.g. Basset Hound and Dachshund) to avoid disorders of the vertebral column' and 'to avoid difficulties in movement and joint deterioration from bowed legs in Basset Hounds, Pekin Palace Dog and the Shih Tzu'. This latter problem is listed under 'abnormal positions of legs'; the breeds identified in both conditions are, it is stressed, only examples not exclusions or inclusions. British breeders are not at present 'guided' by such legislation. To assume however that future immunity is guaranteed is not very wise; the debate needs to be conducted and this 'warning shot across the bows' heeded.

Any debate conducted on this issue would have to address these key questions: Are the legs shorter and the backs longer in some breeds than originally intended when the breed was established? If so, surely breed type is being sacrificed for breeder whim. Are disorders of the vertebral column created by the proportion of back length to leg length? And, finally, do bowed legs create movement difficulty and cause joint deterioration in some breeds bred to perpetuate that feature? Dealing with the first question, there is plenty of pictorial evidence that in some breeds, backs are now longer and legs shorter than in the early specimens in a number of purebred dogs. This has happened over so many years that it has hardly been acknowledged by breed fanciers. But at what stage does this exaggeration have to be halted? Surely when dogs are discomforted by such gradual but still deleterious development.

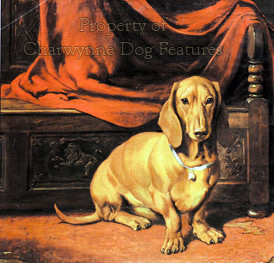

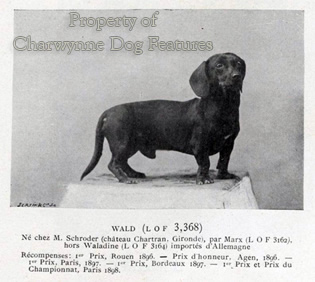

For breeders to plead that essential breed type is threatened and to deny any change in their breed's phenotype is hardly sustainable. Depictions of Dachshunds and Basset Hounds in past centuries show far more daylight under the legs and a marked decrease in the ratio between leg length and back length than in today's specimens. Either breed type then was wrong or breed type today is wrong. Do contemporary breeders keep faith with those visionaries who developed their breed or do they accept a gradual development away from the original type? Who are the guardians of breed type?

To plead function as a justification for exaggeration never withstands scrutiny; function alone never demands exaggeration, with the most functional breeds being the least exaggerated, as the pastoral breeds ably demonstrate. Some argue that more than a few breeds originate as 'sports' of a bigger breed, e.g. the possible emergence of the Lancashire Heeler from small Manchies and the Dachshund from the Dachsbracke and that from the German scenthounds. But smaller varieties of a breed are usually proportionately smaller, as the Munsterlanders, the Portuguese Podengo and the Poodle demonstrate. But crooked legs are a different matter.

The Basset Hound and the Dachshund are examples of achondroplasic animals; achondroplasia is not a disease but an inherited condition in which the long bones of the leg do not attain normal length, disproportionate dwarfism in effect. Scientists tell us that the achondroplasic short-leg gene affects heavy bone more than fine bone and that it will therefore be more difficult to obtain a short-legged dog with straight legs if the bone is heavy than if it is light. It is not surprising therefore that the straight-legged English Basset of the hunting field has appreciably lighter bone than the crooked-legged standard show-type Basset. In their book, Medical and Genetic Aspects of Purebred Dogs (Forum, 1994), Clark and Stainer report that "The Basset Hound is placed in the chondrodystrophoid group of dogs. The conformation of the breeds in this category leads to many inherent problems. The most common problem in the Basset is the high incidence of shoulder and foreleg lameness. There appears to be a high incidence of osteochondritis dessicans. Deformities of the distal radius, ulna and carpal joint are frequently seen."

These words, from veterinary experts, provide all the evidence needed to justify arguments in favour of ETS 125. In their coverage of the Dachshund, these authors state: "Intervertebral disc disease is a particularly dangerous and, unfortunately, common crippler of Dachshunds. The breed is predisposed because of its conformation..." Breeders may wish to dispute such words and refer to their own stock, but at European Convention level, who will the legislators heed? Writing on this breed in his valuable The Conformation of the Dog (Popular Dogs, 1957) RH Smythe states: "...it is evident that the weight of the body, which is considerable, is carried upon spinal bones of more than normal length and that the greater concussion is transmitted to the spine, on occasion, because the Dachshund's legs are short and devoid of flexion or elasticity. This appears to be the reason why individuals of this breed so frequently develop 'slipped discs'."

There is a weight of veterinary evidence to support those wishing to see ETS 125 ratified here. In another of his books, RH Smythe, himself a vet and exhibitor, wrote, in The Dog - Structure and Movement (Foulsham, 1970), "So far as their spines are concerned the most unfortunate are the long-backed dogs, especially the Dachshunds. The abnormal length of spine between the wither and the croup is unsupported at its centre so that undue strain falls upon the intervertebral articulations and the intervening cartilaginous discs. It has been said that the normal life of dogs of this breed is fourteen years, but the spine is good only for five years. Although Dachshunds tend to suffer at intervals from disc trouble with temporary recoveries, the tendency is for ultimate paralysis to develop at a comparatively early age."

Words like these are meat and drink to the anti-KC, anti-purebred dog lobby. The wording of the breed standards of the short-legged breeds are promulgated by the KC; the Dachshund is required to be 'long and low'; the Basset Hound is required to be short-legged and long-bodied. Does that not encourage the breeding of dogs which fit those descriptions, which convey an immediate impression of phenotype to any reader. The breed standard of the Dachshund also states that "The Dachshund is a long low dog as befits his purpose in life, entering a badger set..." Yet other breeds specially developed to go underground after vermin do not need to be so 'low and long'. It is not good sense to attempt to justify exaggerations with a false provenance. And, in these days of widespread moral vanity, it is unwise to condone word pictures which encourage conformation which discomforts the dog. Why feed your potential opponents?

When I see the English Basset, the hunting variety, I see a sound symmetrical hound free of any exaggeration. Straight-legged Bassets are not a modern re-creation; both straight and crooked-legged types have been promoted, but the straight-legged type did not survive as a show dog. The Dachshund is favoured here, whereas its sister breed, the more symmetrical Dachsbracke, despite being introduced in the past has never found favour. Do we actually prefer exaggerated dogs and is that preference supported by a supine KC? When I lived in Germany, my German friends regularly accused my countrymen of favouring exaggerated breeds, citing the King Charles Spaniel, the Bulldog, the show Basset and the show Dachshund. They took me to see Teckels hunting, gleefully pointing out the differences between these admirable little hounds and our show dogs, technically of the same breed.

The French hunting Bassets too are sounder in physique; the Fauve de Bretagne, the Artesien-Normand, Bleu de Gascogne and the Griffon-Vendeen have never received the same increases in ear and back length or decreases in leg length than those excesses achieved here in the standard Basset. But then the German Hunt Terrier has the same leg length now as when it was first developed. Our Scottie is lower than its ancestors, and longer-coated; the same is true of the Skye Terrier. Breeds with a sporting role should have some protection from exaggeration but once that role is ignored, breed points become points to score from and breed characteristics become breed peculiarities and then exaggerations. Dogs intentionally bred with crooked legs and a brisket touching the ground tell you more about human standards than Breed Standards. Every dog bred with an untypical handicapping exaggeration has been bred knowingly with that feature by someone claiming to 'love the breed'; that for me is the saddest aspect of this whole business.