1042 THE SADNESS OF DOG ATTACKS

THE SADNESS OF DOG ATTACKS

by David Hancock

There is plenty of sadness contained in the pages of our daily newspapers but for any dog-lover the greatest sadness is reading of people, children especially, being attacked by dogs. Journalists are quick to identify the type of dog concerned each time, usually blaming 'Pit Bull Types' or 'Mastiff-crosses'. The poor old Staffie is also regularly identified, without any mention of the owner-type - a possible cause of the sad incident. Human judgement, or rather a lack of it, is often the cause of regrettable dog attacks, not just foolishness such as leaving a youngster alone with a dog not used to small children or letting children play noisily next to an insecure garden where powerful dogs are being contained or even bred. I have long campaigned for a breeding licence to be mandatory before any litter can be bred. We are allowing too many dogs to be bred whilst too many are in rescue; we are allowing dogs to be bred for profit and worst of all, we are condoning the breeding of dogs without any thought to their future temperament. This is quite why the sadness of dog attacks happens.

In his enlightening book How To Breed Dogs, written as long ago as 1947, the highly experienced dog-breeder Leon Whitney wrote: "Now, as every breeder knows most dogs are bought on the basis of what cute puppies they are. The buyer hardly stops to ask, ‘Will it have a calm even disposition when it is grown?' Nor does the breeder usually stress disposition. Instead he brags about the wonderful champion show dogs in the pedigree - anything to sell the pup. Why can't breeders all realize that what makes dogs lastingly popular is first, disposition?" If the general public buy puppies without any regard to their likely temperament, is it at all surprising that children get bitten, breeds can get a bad name as a result and fewer sales in that breed ensue. Most 'returned' puppies are done so because of their behavioural defects. But were their parents carefully chosen or even selected at all?

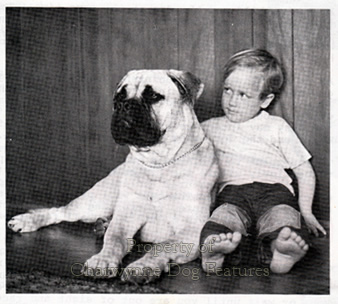

Surely the very first question any responsible parent should ask when considering a future family pet is: 'What is the temperament of the parents and previous litters from this mating?' Every breeder of purebred dogs needs sales to pet homes to sell litters; who is going to recommend breeders of dogs likely to have undesirable temperaments? The biggest single cause of dogs from a powerful breed, like the Bullmastiff, going into rescue is their temperament. What possible solace is there in saying later, in sorrow, that it was such a cute puppy! ' What comfort is it to be told that the dog that bit your child had ancestors that won Crufts? Even accredited breeders are not obliged to put temperament high on their list of desired qualities. Is this the best way to promote the breeding of companion animals? Is this the best way to promote the breed you love? Is this the best way to improve the man-dog relationship? Selectivity really does matter; selecting the breeder really does matter. Selecting the right genes is the key not just to breeding but successful ownership too.

There's a subject far more important than rosette-winning, judging appointments or committee posts and it's one so often avoided or evaded. It concerns temperament, especially in the breeds of powerful mastiff-type dogs (and I include the American Bulldog here). Any untrustworthy dog is a menace; an untrustworthy large dog is doubly dangerous. Mastiffs and Bulldogs are notoriously laid-back but crosses with these breeds have been recorded as a potential problem. Sadly, any huge dog with a black mask and a broad muzzle is quickly described as a Bullmastiff. Three mastiff-type breeds are proscribed in the UK's Dangerous Dog Act: the Japanese Tosa, the Fila Brasileiro (the breed most tested in the whole world for temperament) and the Dogo Argentino; each of these breeds is banned from Britain, despite being the national breed in their respective countries. Straightaway this ban gives such breeds, by type, a wholly misleading and unfortunate association. But breeds do not need a savage nature to arouse suspicion. In a letter to me, Chris Ryder of Bullmastiff Welfare once wrote: "The number of animals coming in is increasing all the time, and many people who approach us have an animal which we can't rehome because of temperament problems. I'd love to have a definitive answer as to what causes bad temperament. Is it bad upbringing, heredity, own nature?"

Chris also subsequently wrote in Lyn Pratt's Our Dogs breed notes: "...the number of animals who cannot be rehomed because of temperament faults is approximately half the number of those who are rehomed." This, at a time when the breed has been targeted in Germany under their dangerous dogs legislation, was very bad news. It is rare but not unknown for Bullmastiffs to be banned by the Kennel Club for attempting to bite the judge in the show ring, along with dogs from other breeds of course. But it is not unknown either for the dreaded 'kennel blindness' to affect those with Bullmastiffs of untrustworthy temperament, even to the extent of breeding from such flawed stock. I don't have a problem with male dogs which are a bit sharp with other dogs or bitches that take a dislike to a litter-sister or dogs with a strong guarding instinct. The problem lies not with dogs with predictable attitudes but those which bite humans without warning and for no discernible reason. These are the dogs that are capable of shaming the breed, or, worse, getting the breed banned as a dangerous one. This is a topic which more than any other at the moment demands a debate. If not, this precious breed will face an uncertain future.

Chris Ryder mentioned three possible causes of bad temperament: bad upbringing, heredity and the dog's own nature, unrelated to its breeding or upbringing. Bullmastiffs can be a very dominant breed and with their heritage that's hardly surprising. But a dog of this size, allowed to be too dominant, is a definite danger. We all know of cases where the dog is allowed the run of the house, to replace its owner as pack-leader and display unwanted assertiveness without being checked. A well-known breeder used to warn visitors "Don't look at the dog when I let him into the room"; another would warn "Don't stand up whilst the dog is with us" and another would advise "Whatever you do, don't touch him!" Such warnings tell you more about people than about their dogs. You have to ask the crucial question: Who's in charge, the dog or the owner? Such dominance-displays are quite intolerable and in a small pack of dogs horribly dangerous. Yet there are well-known breeders who allow their dogs to take charge, to assert themselves, to become the boss. One Bullmastiff elder, ever ready to pronounce on the breed, was once forced to take refuge in his own bedroom when his dominant dog (not a Bullmastiff) asserted itself too forcibly. There is a huge difference between a perfectly natural guarding instinct and an unacceptable degree of dominance. When I was a soldier I had experience of guard-dogs, anti-ambush dogs, tracker dogs and detection dogs; those in the first two categories could be more than fierce - but they were always under control.

Upbringing clearly matters a great deal. My first two Bullmastiffs were both male and lived with us as pets. Their early squabbles as pups were quickly and very firmly dealt with and they subsequently grew up to be contented kennel mates. But breeding matters more. What do scientists tell us about the inheritance of temperament? The American Vet Leon Whitney crossed a Bull Terrier, regarded as a natural killer and fighter, with a placid Bloodhound. He found that two of the resultant pups, all raised the same, possessed suspect temperament, one having to be destroyed because of his innate aggression. Another mating between a placid Bull Terrier and a Bloodhound produced no offspring with flawed temperament. Of the fourteen pups from these two matings only two had faulty temperaments, both from the aggressive Bull Terrier bitch. Humphrey and Warner, in their Working Dogs of 1934, showed that excessive timidity, which can lead to 'fear-biting', could be bred out, with more than one factor or gene governing this trait. Bold, confident dogs with controlled dominance have been found to be less likely to bite people than excessively timid dogs. The latter should never be bred from. The guarding instinct is strongly inherited; wilful pups sold to unsuitable homes can end up creating problems for their new owners. The experiments of Kruskinsky showed that excessive shyness, which can lead to 'fear-biting', increased markedly when two shy dogs were mated to each other.

In his Genetics for Dog Breeders of 1990, Roy Robinson writes on breed differences: "That inherited differences do exist is indisputable, as shown by the various breed categories with different modes of behaviour. A small part of this variation could be imitative or learnt from the mother, siblings or older members of a kennel, but the major part is instinctive." This means that an aggressive dam can adversely influence her offspring both before and after their birth. It means too that an over-aggressive male dog can influence the younger members of the same kennel. Robinson went on to state "...there is the excessively excitable, nervous or highly-strung animal...such behaviour is likely to be inherited and individuals showing such behaviour should not be used for breeding."

In his Practical Genetics for Dog Breeders of 1992, Malcolm Willis wrote: "Cowardly or excessively aggressive animals have no place in any breeding programme no matter how beautiful they may be." He sets out a table which shows that the heritability of nervousness is 50% and that of temperament 30-50%. Abnormal temperament can be a matter of chance too as Hodgman indicated in a 1963 study; he did stress however that selection in certain breeds for assertive behaviour made this more likely. Thompson in 1957 showed that the individual dog is subjected to external influences which affect its behaviour from the moment of birth but it is likely that heredity is a major contributor to behavioural traits. Socialisation is clearly an important factor in later behaviour. Eberhard Trumler, in his highly perceptive book Understanding Your Dog of 1973, wrote: "Again the behaviour of the dog which has been badly brought up during its socialisation phase will later bear an astonishing resemblance to that which, in human society, leads to the drop-out or the criminal." Pups which have simply been left to starve spiritually in an outhouse from three to seven weeks of age will find the real world a frightening and daunting place. That is why puppy-farms are such a danger to the production of future family pets. Abnormal aggression is a defence mechanism in a fearful dog. Territorial aggression is natural but still requires controlling. Young dogs have much to contend with: inadequate socialisation, aggression inherited from their forebears or aggression picked up from imitating older dogs.

The distinguished canine behaviourist Michael W Fox, in his book, also entitled Understanding Your Dog, of 1974, wrote: "Too many breeders are selecting solely for conformation, for 'showy' or 'stylish' looks, which often become distorted, mimic exaggerations of the original breed standards. Insufficient attention is paid to selecting for stable temperament and for trainability and, consequently, many breeds are becoming suburban status symbols - ornaments, not companions." He's right, of course, the evidence is before us. Would a show breeder breed from the sharp-tempered but otherwise outstanding dog or the calmer more trustworthy slightly less high quality dog? Most of the offspring will become pets. For those who really love their breed, as opposed to those who impress upon you how much they do but then proceed to breed from unstable dogs, the choice is very clear. Either give temperament a higher priority or risk seeing your beloved breed banned from whole countries. All Mastiffs, Bullmastiffs and Bulldogs in the world originated in British stock. If we breed and then export specimens of these breeds with unsafe temperaments we put at risk the whole future of these splendid breeds. If we breed and then sell pups from 'iffy' parents to pet homes we deserve all the legislation we are threatened with. Why not listen to what those remarkable individuals involved in breed welfare are saying to us? The alternative is frightening enough: goodbye breed! We must control the breeding of powerful dogs; dog attacks are unacceptable in society but hand-wringing is simply not enough. The protection of children must always come first but control over the breeding of strongly-built dogs must surely be seen as a factor in this.