885 SIGHTHOUNDS IN INDIA

SIGHTHOUNDS IN INDIA

by David Hancock

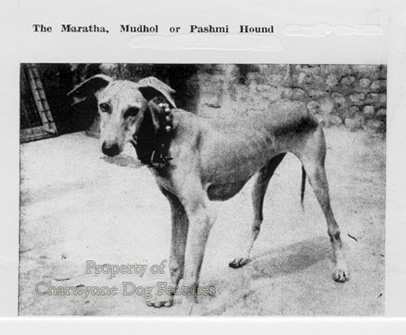

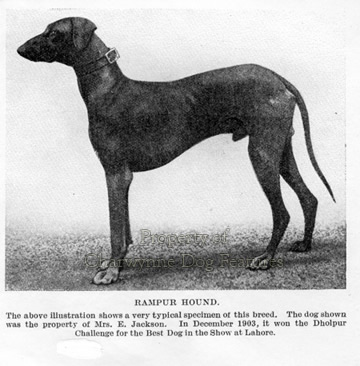

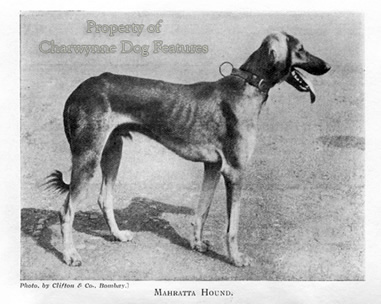

The deserts of the Indian sub-continent have proved good hunting grounds for sighthounds. The Sindh Hound is found in the deserts of Sindh and Rajasthan and famous as a boar-lurcher, being Great Dane size: 28 to 30" and around 100lbs in weight. Lighter and more Sloughi-like is the Rampur Hound, the Greyhound of Northern India, the Maharajah of Baria once having a famous kennel. Around 28" at the shoulder and weighing around 75lbs, they have been used on stag and boar and for hunting jackal. A century ago, some were brought to Britain and exhibited at the Dublin show. The lurcher of Maharashtra is the Mudhol Hound, between the Greyhound and the Whippet in size. More Saluki-like is the lurcher of the Banjara, a nomadic tribe with gypsy conections. The Banjara, or Vanjari, is famed for its stamina and nose and its ability to pull down deer, always going for the hindquarters, not the throat, as many Deerhounds do instinctively. The Poligar and the Vaghari have a distinct smooth Saluki look to them.

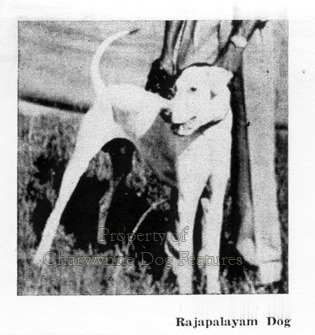

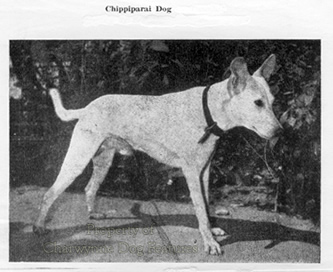

The Chippiparai, the lurcher of the south, is described as being Dobermann-like in outline, but usually white in colour and used mainly for hare-hunting. They are regarded as the most intelligent and biddable Indian breed, being used as police dogs in some areas. The Poligar Hound is the Greyhound of Southern India; they have been called the lurcher of India, used on fox, deer, jackal, and, in packs, on boar. For generations this breed was used for pig-hunting on foot with spears, rather as the ancient Greeks hunted them. Around 26" at the shoulder and weighing between 40 and 45lbs, they are thin-coated but the coat has a stiff wiry texture, harsh to the hand when back-brushed. They are famous long-distance runners but sadly for a delicate constitution, needing careful rearing. The hunting dogs of the nomadic Indian peoples today fall into two types: the lighter-boned smooth-coated Mudhol or Karvani dogs and the stronger-boned silky-feathered Pashmi or Pisouris, which can range from 20 to 28". They are used on a wide variety of quarry, from chinkara and blackbuck, fox and rabbit to civet and mongoose, even black-faced monkeys, a local pest.

Nomadic tribes, moving between Persia, India and Afghanistan, made great use of sighthounds as pot-fillers. In The Kennel Encyclopaedia, Volume 2 of 1908, edited by J. Sidney Turner, under the section entitled Greyhounds (Eastern), there is extensive coverage of the Afghan Hound but under the title The Persian Greyhound, with good illustrations of early import Zardin. The text contains these words: “From Seistan, in Persia, are obtained very heavily coated hounds, mostly fawn in colour, with black faces…Dogs of this type are to be found at Chageh (Biluchistan-Afghan border); at Nasratabad (Persian-Afghan border) – both places wide apart; as well as over a large area on the Eastern Persian borders. The Afghan hound, also known as the Barakzai, Kurram Valley hound, and Kabuli hound, is to be found in more or less numbers all along the borderland and Northern India. It is often kept even further South for hunting purposes, where it eventually loses the greater part of its coat.” Zardin, on whom the first Afghan Hound breed standard was based came from Chageh in the vast Mekram area of Persia, not from Afghanistan. The British in India made use of sighthounds from further north, in areas where international boundaries, observed by Western governments, meant little to nomads. Sportsmen in India made wide use of hunting dogs from further north.

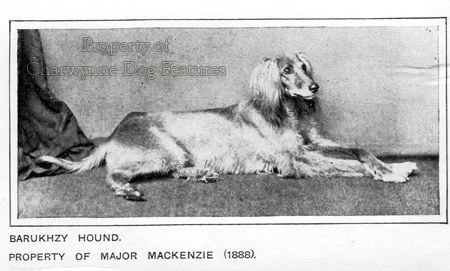

In the hunting field, Sir Harry Lumsden, when with the British Army in Kandahar at the time of the Indian Mutiny of 1857, was not impressed by the hounds he saw, writing: “The dogs of Afghanistan used for sporting purposes are three sorts: the greyhound (Afghan Hound), Pomer and Khundi. The first are not formed for speed and would have little chance on a course with a second-rate English dog, but they are said to have some endurance and, when trained, are used to assist charughs (hawks) in catching deer, to mob wild hog, and to course hare, fox, etc.” Later, a Major Mackenzie wrote to advise Drury in his British Dogs of 1903, to say that “The sporting dog of Afghanistan , sometimes called the Cabul Dog, has been named the Barukhzy Hound from being chiefly used by the sporting sirdars of the royal Barukhzy family. It comes from Balkh, the north-eastern province…” going on to describe how one hound killed a leopard that had seized her pup. This would have been some hound, both in size and determination. Drury provides an illustration of such hounds.

Mackenzie went on to describe the hounds in the hunting field: “They usually hunt in couples, bitch and dog. The bitch attacks the hinder parts; while the quarry is thus distracted, the dog, which has great power of jaw and neck, seizes and tears the throat. Their scent, speed and endurance are remarkable; they track or run to sight equally well. Their long toes, being carefully protected with tufts of hair, are serviceable on both sand and rock.” He gave their size and weight as from 24” to 30” and 45 to 70lbs. The ones he used were fawn or bluish-mouse, always darker down the spine, with a smooth velvety coat texture.

In Croxton Smith’s Hounds and Dogs of 1932, there is also an idea of their sporting use: “The quarry, a small very swift deer called Ahu Dashti, is hunted by Afghan Hound with the aid of hawks…The young birds and Afghan puppies are kept together, fed on the flesh of deer. When fully grown, the hounds are loosed after a fawn and the hawks flown at it…The Ahu Dashti or chinkara, as it is known in Indian, is so swift that it is said that, ‘The day a chinkara is born, a man may catch it; the second day a swift hound; but the third, no one but Allah.’” She went on to describe hearing of a pack of chinchilla hounds, always grey with black points. She wisely stated that: “Many of our breeders and judges today clamour for size, for bigger hounds at any cost. The Afghan Hound is, or should be, of the greyhound type but sturdy, compact and capable of endurance in order to enable him to hunt all day over the barren, rocky, precipitous mountains of his own land. The struggle for height so often results in coarseness or weediness at the expense of quality. The origin of the Afghan Hound is lost in the mists of antiquity but his Afghan master has kept the breed unaltered for some two thousand years. It seems a pity to alter it now for the English show bench.” There goes a lament echoed in so many sporting breeds of dog.