884 SIGHTHOUNDS OF AFRICA

SIGHTHOUNDS OF AFRICA

by David Hancock

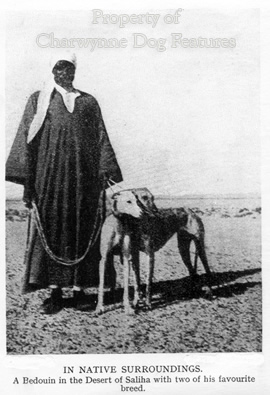

Find a desert and a sighthound will not be far away and Africa is not short of deserts. For a hound that hunts by speed and capitalises on superb eyesight, the desert is the hunting ground to excel in. The Saluki, the Sloughi, the Azawakh and the I-Twini much further south all exploit their remarkable sprinting ability and capability to detect animal movement at long range. They are pot-fillers where other predators do not succeed; they are canine hunters where other sporting dogs cannot hunt. Only the cheetah rivals their success, with perhaps the Abyssinian wolf a contender. The Saluki is easily the best known desert sighthound, with the feathered variety well-established in Europe, but the French have long fancied the Sloughi.

Find a desert and a sighthound will not be far away and Africa is not short of deserts. For a hound that hunts by speed and capitalises on superb eyesight, the desert is the hunting ground to excel in. The Saluki, the Sloughi, the Azawakh and the I-Twini much further south all exploit their remarkable sprinting ability and capability to detect animal movement at long range. They are pot-fillers where other predators do not succeed; they are canine hunters where other sporting dogs cannot hunt. Only the cheetah rivals their success, with perhaps the Abyssinian wolf a contender. The Saluki is easily the best known desert sighthound, with the feathered variety well-established in Europe, but the French have long fancied the Sloughi.

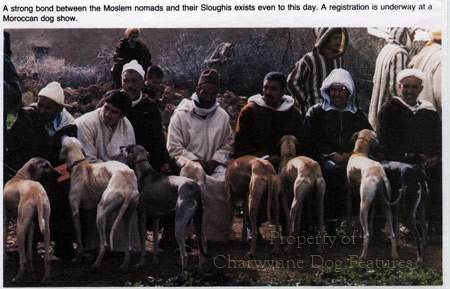

There is no single type of Saluki. Most of the hounds I've seen in middle eastern countries have been smooth-haired (the Nejdi type), not feathered (the Shami or Syrian type). The smooth coat is dominant. In the pedigree world we have smooth and feathered hounds registered as Salukis, with the smooth-coated Sloughi (from North Africa) listed as a separate breed. The Arabs there however referred to them as mogrebi or western. The Tuareg Sloughi, sometimes known as the 'oska', is classified separately in some countries as the Azawakh Sloughi, from the valley of that name in Mali and Niger. Both the Azawakh and the Sloughi have been found to possess an additional allele on the glucose-phosphate-isomerase gene locus, not found in other sighthounds but also featuring in the jackal, suggesting a separate origin. Circassia, in the Caucasus, was once famous for its sighthounds; but Circassians can be found in Syria, Iraq, Jordan and Turkey too.

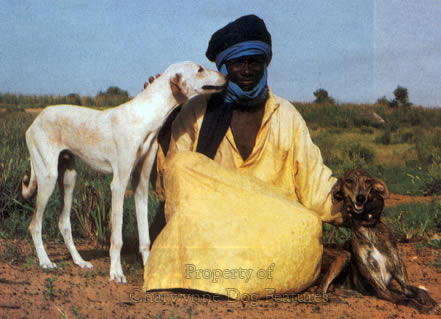

The Azawakhs come from further south, a breed that has lived for thousands of years with the nomadic tribesmen of the Berber and Tuareg. Azawakh means 'land of the north' and spans Niger and Mali. Unusually for a sighthound breed the Azawakh is also used as a herding dog and watchdog. If the Sloughi is the Arabian sighthound, then the Azawakh is the African one. Their temperament is alleged to be more feline than canine, perhaps from their natural aloofness and independence of mind. Looking taller than the other sighthound breeds, they have thin skins, a prominent sternum and very deep chest and a very high tuck-up, making some look almost skeletal. Body ratios are considered important in this breed: height of chest/ height at withers = about 4:10, length of muzzle/length of head = 1:2 and width of skull/length of head = 4:10. Often confused with the Sloughi, especially the desert type in this breed, the mountain type of Sloughi being taller and more robust. The desert sighthounds of the world are true lurchers; most are unrecognised and unregistered, but they have been carefully bred to function. They should never be underestimated as highly effective hunting dogs, surviving hard times in tough places. The words of James Wentworth Day, in his 'The Dog in Sport', Harrap, 1938, tell you much about desert hunters and their reverence for their hunting dogs:

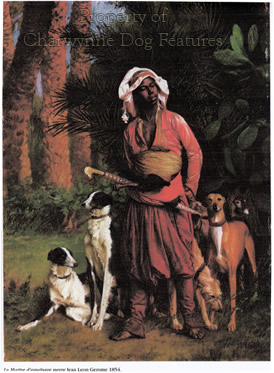

"The Sahara Desert tribes call the Saluki Barake, or 'Specially Blessed'. Nowhere in North Africa or Arabia is the Saluki ever sold between tribes or members of tribes. He is always given as a present of honour either to an eminent guest or to a favoured friend. In the Libyan Desert the tribesmen speak of this graceful hound as el Hor, 'the Noble One', and they say of him as they say of their horses: 'are not these the herited of our fathers, and shall not we to our sons bequeath them?'" Primitive people knew the value of their hunting dogs; in more developed countries today we merely exploit them.

Of a totally different type are the tribal dogs of South Africa. This remarkable group of dogs has been researched and then publicised by Johan Gallant in South Africa, after centuries of European indifference. Any group of dogs which can survive without ever receiving any veterinary care, in a testing climate like the South African bush and operating in terrain which would challenge any functional animal, deserves attention. The Africanis is believed to be a direct descendant of the domestic dogs which came to southern Africa with the Iron Age migrations of the Bantu-speaking people. These dogs were then taken up by the resident Khoisan people; these dogs were never bred for type but type developed from function.

Natural selection has not only eliminated inheritable diseases and provided a natural resistance to internal and external parasites, it has created a virile, healthy, functionally excellent animal, repeating the formula applied automatically by primitive dog breeders all over the world. It is only in the highly civilised countries where, paradoxically, sickly short-lived dogs are bred from because they are handsome or conform to a rigid blueprint. There is nothing exaggerated or extravagant in the Africanis; their coats adapt to the seasons, they move with great economy of movement and their owners have no obsession with ear carriage - their dogs can have drop ears or erect ones. These dogs have survived in a harsh setting and are genetically important.

The generic term Africanis embraces several types of dog; the I-Twina, now quite rare, is a living representative of the Iron Age dog, and a sighthound described as the original hunting dogs of the Xhosa. The I-Baku, big or floppy-eared in the Xhosa tongue, longer-haired and featuring a hind dew claw, is the long distance sighthound, unlike the I-Twina which is a sprinter. The I-Nqeqe, or I-Maku to Zulus, conforms to the same type, but has a blunter shorter muzzle. Some Europeans have noted a certain Border Collie look to these dogs, which are found across a wide area. The more streamlined I-Bansi are the most competent hunting dogs, able to hunt using sight and scent. The Zulus have their Sica dogs, which can vary in appearance, never having been subjected to selective breeding, and can be found right across the Zulu homeland.

.jpg)

.jpg)

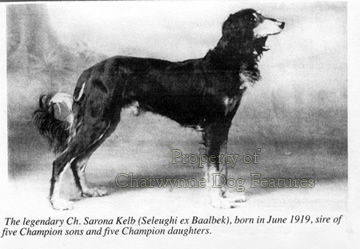

We have to be extraordinarily careful that in the pursuit of show success, whether in lurcher rings or at KC-licensed events, we do not end up destroying the key elements in these handsome functional speedsters. A sighthound needs lung and heart room in abundance; it must have great forward extension, facilitated by sound shoulders. Short straight upper arms are creeping into so many sporting breeds these days and it is introducing quite untypical and most undesirable movement. The importance of sound shoulders can never be stressed enough in any hound breed. A hound built for speed, whether a Spanish Galgo, a Hungarian Agar, a Tasy or a Taigon from Mid-Asia, a Moroccan Sloughi or an Azawakh from Mali, must have the anatomical attributes that provide sprinting power. Some foreign sighthound breeds look different now from the original imports; the Afghan Hound certainly has more coat and the Borzoi can feature a markedly convex back as opposed to the more or less level topline of the early imports.

Hunters and sportsmen the world over know that the ability to catch game using speed demanded a very distinctive build. The sighthounds bound; they must have the height/weight ratio, the leg length and the liver-size to sprint. Sighthounds race entirely on liver glycogen, sugar activated from the liver. Sprinting demands long legs and a sizeable liver. The bigger the liver the more sugar can be stored. A sighthound over 65lbs in weight would theoretically have more of a problem through heat storage, although their streamlined build allows the presentation of a greater surface area. We are good at getting rid of excess heat and not very good at storing it. Dogs are the reverse, removing excess heat from their surfaces rather as a radiator gives off heat.

When sighthounds were traded, such technicalities were not known but the radiator-like build, size without weight and long legs meant something to their traders. The most successful sprinters had the build to succeed and were traded and perpetuated.

In breeding for appearance only we need to bear in mind those anatomical essentials that made sighthounds what they are: internationally renowned sprinters. An 85lb Borzoi will experience difficulties when running flat out; a Greyhound of any weight with a small liver will have an even bigger handicap. Traders in such hounds couldn't measure livers but they could measure performance. Some of these overseas breeds are being perpetuated here only in the show ring. The worry is that, in time, show ring criteria will shape them, not function. Commendably, some of the Saluki owners in Britain have coursed their hounds and now use them for lure-chasing. These superb hunting dogs were bred to exacting standards by expert huntsmen over many centuries; the very least we can do in these constricted times is to let them stretch their legs, really fly; let their instinctive behaviour manifest itself; give them spiritual contentment.

In breeding for appearance only we need to bear in mind those anatomical essentials that made sighthounds what they are: internationally renowned sprinters. An 85lb Borzoi will experience difficulties when running flat out; a Greyhound of any weight with a small liver will have an even bigger handicap. Traders in such hounds couldn't measure livers but they could measure performance. Some of these overseas breeds are being perpetuated here only in the show ring. The worry is that, in time, show ring criteria will shape them, not function. Commendably, some of the Saluki owners in Britain have coursed their hounds and now use them for lure-chasing. These superb hunting dogs were bred to exacting standards by expert huntsmen over many centuries; the very least we can do in these constricted times is to let them stretch their legs, really fly; let their instinctive behaviour manifest itself; give them spiritual contentment.

.jpg)