850 THE NEEDS OF THE SIGHTHOUND

THE NEEDS OF THE SIGHTHOUND

by David Hancock

Keystone ‘Bridge’

Keystone ‘Bridge’

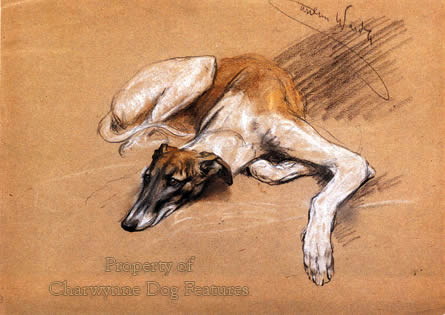

When breeding sighthounds, it is vital to be quite clear on their needs, that is, what allows them to hunt at speed. For me, shoulders and loins are the crucial ingredients for a quality sighthound. The flexibility needed when say a Greyhound is racing is quite astounding: the hind feet 'overtake' the fore feet, with the loin and the thigh both curved into just about a semi-circle when the hindlimb is stretched forward to its very limit. The elasticity which permits this is astonishing, but the soundness of construction and muscularity of the dog allows it. The loins have no support at all from any bones other than the seven lumbar vertebrae and act as the crucial link, the keystone 'bridge', between the front limbs, from the ribs forward, and the rear limbs - the legs, pelvis and tail. For structural strength, a slight arch here is essential, but too great an arch is a weakness. That is why the gift of 'an eye for a dog' puts one judge in a different class from another. A desirable arched loin can be confused with a roach or sway back.

Most Important Single Factor

A dog may get away with a sagging loin in the show ring or even on the flags at a Hound Show; but it would never do so as a working or sporting dog. It would lack endurance and would suffer in old age. Yet it is, for me, comparatively rare to witness a judge in any ring in any breed test the scope, muscularity and hardness of the loin through a hands-on examination. For such a vital part of the dog's anatomy to go unjudged is a travesty. It doesn't take much imagination to appreciate the supreme importance of the loins to the speedsters, the sighthound breeds. Some Greyhound experts have argued that the muscular development of the back is probably the most important single factor in the anatomical construction of the Greyhound, ahead of the muscular hindquarters.

Supple Firmness

Through the centuries, the writers’ words have been consistent: Berners - 'Backed lyke a beam'; Markham - 'A square and flat back, short and strong fillets'; Cox - 'Arched, broad, supple and showing enormous muscular development'; ‘Stonehenge’ - 'The loins must therefore be broad, strong and deep, and the measure of their strength must be a circular one'. In his informative book on the Greyhound, Edwards Clarke writes: "The very first test that any trainer makes of the condition of a greyhound is to run his hand over its back and loins...The first impression by touch should be one of supple firmness, of well-developed muscular tissue of a rubber-like consistency." He sought a little trough or valley along the backbone. He looked for arching of muscle not any arching of the skeleton, a common fault in our show sighthounds, especially in Whippets and Borzois.

Arched Loin

Clarke termed the roach or 'camel' back a skeletal malformation, a form of spinal curvature that 'militates against any possibility of smooth-flowing, free-striding movement'. At a championship show a few years ago, I saw a lady exhibitor proudly posing her winning Greyhound for the dog-press photographers despite its very obvious camel back! The somewhat brief breed standard for the Greyhound stresses an arched loin both in the General Appearance and the Body sections; perhaps a few more words on the need for a muscular arch rather than a skeletal arch would be a better guide. The standard of the Borzoi actually demands a back that is boney, free from any cavity and rising in a curve. The Whippet is expected to feature a definite arch over its loin; the Borzoi however is supposed to possess the highest point of the curve in its back over the last rib, i.e. forward of the loin. Both are sighthounds built for speed. The American standard for the Borzoi calls for a back which is 'rising a little at the loins in a graceful curve'. That is more than a little different from ours and more likely to produce an efficient sighthound. There is a world of difference between a bent skeleton over the last rib and a curve of muscle over the loins, the latter benefiting the dog! The lumbar vertebrae are quite literally the backbones of the loins, lumbus being Latin for loin. Any arch should be over the lumbar vertebrae and not further forward.

Transmission from the Loins

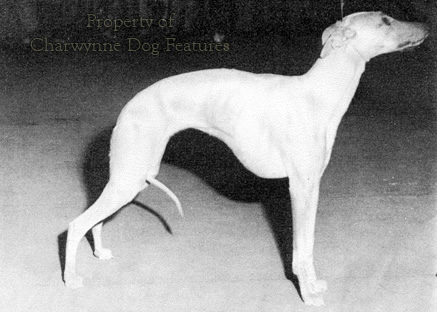

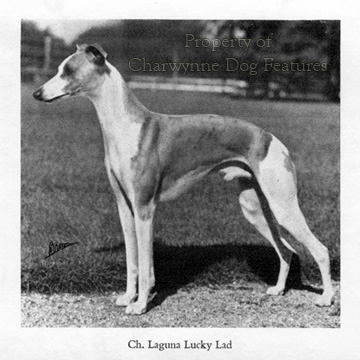

In an attempt to appreciate the value of the loin to the dog, I think of the dog as a four-wheel drive rear-engined vehicle with its transmission in the loins. They are an absolutely key feature of the canine anatomy relating to movement. If we prize movement then we must understand the loins. But just try researching the subject even in weighty books on dogs. It is vitally important for any serious sighthound breeder to learn about loins. Coursing men did, as Frank Townend Barton MRCVS in his Our Dogs, Jarrolds, 1938, states: “All coursing men pay particular attention to depth of chest, quality of back and loins, and still more to the hindquarters – i.e. the rump, the first and second thighs as well as the hock joints and pasterns. It is almost impossible to be too insistent regarding highly developed muscles and broad loins, where so much action is brought into play when a Greyhound is running and twisting after the hare.” Words too from Bo Bengtson's book on the Whippet represent surprisingly rare coverage of this vital part of a dog's anatomy: "To acquire the perfect silhouette the dog must obviously have sufficient length of loin to avoid the cramped, wheel-back stance which has periodically been quite common. This extra bit of loin is what makes the dog cover a lot of ground and was what Mrs McKay at the Laguna kennels always impressed on me made all the difference between an ordinary whippet and a top-class one." It is good to see a knowledgeable show ring judge and international Whippet expert appreciating the value and importance of this vital area of the anatomy of the running dog.

Visible Power

One hundred and fifty years ago, in the early days of showing, running dogs were regularly exhibited: the winner of the Waterloo Cup in 1855, Judge, won second prize at the 1862 Islington conformation show. Twenty-five years later, Bit of Fashion, dam of the celebrated Fullerton, was exhibited at Newcastle, winning first prize. I find it hard to believe that a specialist Greyhound judge would not admire the powerful hind-limbs, strong sloping shoulders and rounder rib cage of the sporting type. All Greyhounds were once like this; where is the rationale of being attracted to a breed and then wishing to change its shape? Symmetry, gracefulness and beauty are not the essence of a sporting breed, however pleasing to the eye. Every Greyhound should demonstrate physical power, really look like a superlative canine hurdler – a genuine fast hunting dog.

Physical Flaws

In The Kennel Gazette of July 1888, the Greyhound critique made mention of 'a showy black, but flat in ribs...' and a bitch of 'beautiful quality and style, but decidedly short of heart room...' Does 'showiness' compensate for flat ribs? Can a sighthound, designed to run very fast, combine beautiful quality with a lack of heart room? Five years later, a critique praised a 'niceish' black bitch with 'rather upright shoulders' (which came second!) and the reserve card winner a 'pretty' dog 'somewhat cow-hocked'. A critique on the breed just a year ago stated that front movement was really bad, with another observing that muscle tone was very hard to find. A recent Crufts critique on the breed commented on the absence of muscle tone and a lack of spring of rib in the entry. This is depressing. In his The Whippet of 1976, Douglas-Todd wrote: “An upright shoulder in a Whippet is like a man with hunched shoulders. Just try hunching your shoulders and then, with your shoulders up round your ears as it were, try to walk forward smartly and see how you feel.” Front movement depends on well-placed shoulders, well-muscled but not ‘loaded’. A good judge will always spot the difference, but a knowledgeable exhibitor really ought to know such basic flaws.

Feet for Function

Ever since Dame Berners’s much-quoted description of a Grehound (sic) included the words ‘Fottyed lyke a catte’, the sighthound breeds’ foot has tended to be desired as ‘compact’, as in the Deerhound standard. The cat foot has been blurred with the compact foot. The Irish Wolfhound is expected to have round feet. The Borzoi is required to have hare-like rear feet and oval front feet. The Whippet needs oval feet. The Sloughi is preferred with the hare foot and I think this is right. I always associate the cat foot with endurance and the hare foot with speed. Condition can affect the appearance of the feet, with an unfit out-of-condition dog looking splay-footed and slack pasterned. In the dog the toe-pads do most of the footwork. The main difference between a hare foot and a cat foot is the length of the third digital bone. In both shapes of foot this bone should be parallel to the ground but the second digital bone in the cat foot should lie at 45 degrees. Exercise too can when carried out entirely on soft ground can cause the dog’s foot to look more spread out. Hunting country too can influence foot shape, with the Afghan Hound required to display large strong broad forefeet and long hindfeet, to suit the terrain it hunts over. ‘No foot, no dog’ is as applicable to the sighthound as is ‘no foot, no horse’ to that family of animals. But it is crucially important to appreciate that there is a fundamental difference between the locomotive system of the horse and that of the dog; the horse uses what is called the transverse gallop, the dog uses the rotary gallop. A veteran huntsman once gave me the view that ‘horses run with their legs, dogs with their backs.’

Superb Eyesight

Rotary gallop, muscular power, energy storage and soundness of feet apart, the speedsters of the dog world need superlative eyesight. Dogs easily outperform humans in detecting movement, their motion sensitivity allowing them to recognize a moving object from a distance of 800-900 metres away. Motionless, the same object will only be picked up by the dog’s vision at roughly half that distance. Dogs have far superior peripheral vision to us, around 250 degrees, against our 180 degrees maximum. It is no accident that all the cursorial breeds have the same skull outline. Their better depth perception and enhanced forward vision comes from longer nasal bones resulting from a longer nasal-growth period that occurs at an earlier age. As biologists Raymond and Lorna Coppinger point out in their perceptive book Dogs – A Startling New Understanding of Canine Origin, Behavior and Evolution of 2001, when selecting breeding stock for rabbit-catching hounds: “…I would sort through my dogs and pick those that worked best, and breed the best to the best. I might not realize that all I am really doing is selecting for longer nasal bones. The eyes themselves are no better than in any other breed. They are just in a better position to see forward.”

Night Hunting

All animals active at night, whether predators or prey, have a ‘back-up’ visual support system, which gives the retina two opportunities to catch light, greatly enhancing night vision. A highly reflective layer of cells, the tapetum lucidum, underlies the retina and behaves like a mirror. Light is reflected back through the retina, the tapetum offering the photoreceptors a second chance to capture light. This mirror effect, reflecting light back out through the eye, makes predatory animals’ eyes shine in the darkness. Photographs of them pick this up. Dogs’ low-light vision is far superior to that of humans but is still not as good as the cat family, which detects light levels six times dimmer than our eyes can. Cross your coursing dog with a cheetah and you have the hunter by night as well as the hunter by sight! (In 1937, the founder of the Romford track, Archer Leggett, launched a new attraction: cheetahs racing against Greyhounds. After a cheetah bitch had covered the 355 yard course in 15.86 seconds, easily a track record, the experiment was discontinued, allegedly because the cheetahs became bored with inedible prey!)

Seeing the Sights

It could be argued that the group of dogs above all others which need sound eyes is the sighthound group, if only by name. But if you examine the wording of the various sighthound breed standards over the years, there have long been amendments needed. The Afghan Hound eyes have to be 'nearly triangular' without the shape of triangle being specified; that is not helpful to a tyro-breeder. The punctilious could well argue that 'nearly triangular' is a contradiction in terms; a triangle cannot be 'nearly' anything else. Who decides how flat or upright the nearly triangular eye of the Afghan Hound has to be? Of what value is such a loose term? The Saluki and the Sloughi have to have 'large' eyes, but how large? The Greyhound and the Borzoi are expected to feature eyes which are 'obliquely set', i.e. diverging from a straight line, but by how much? The eyes of the Cirneco dell’Etna have to be relatively small – but relative to what? Imprecise wording in a word picture intended to be instructive can be dangerous. The Kennel Club, to be fair, is reviewing the wording of all breed standards, with clearer guidance, especially with health issues in mind, but descriptions, however well-meant, can lead to misguided and sometimes ignorant breeders pursuing a flawed word picture of their breed.

The Skull of the Sighthounds

This collection of sighthound head studies show the skull construction and eye placement that allows the best possible vision for the hot-pursuit hunting dog. These long lean but not too narrow heads, often with a prominent occiput, broadest at the ears, tapering to the muzzle, always with a powerful jaw, displaying little stop, with well-set never prominent eyes and always held high, ever ready to scan the middle distance, are a unique feature of the speedsters. In his The Illustrated Natural History (1928 edition), the Rev J G Wood states; “The narrow head and sharp nose of the Greyhound, useful as they are for aiding the progress of the animal by removing every impediment to its passage through the atmosphere, yet deprive it of a most valuable faculty, that of chasing by scent.” He overlooked the fact that sighthounds use air-scent and operate in country where ground scent is minimal. The hounds from the Mediterranean littoral seek air-scent, using the high head posture, and have bat-ears, relying much more on their hearing and being less vulnerable to icy winds; their heads resemble a blunt wedge and they are usually broader-headed than their northern cousins. The sighthound breeds have more refined skulls than most hunting dogs, facilitating that sighthound aloofness, so much a characteristic of the group. But the whole skull construction is built to permit the best possible vision, probably stereoscopic – like ours, from a high head position, rather than to demonstrate canine elegance.

Measurements of the coursing Greyhound Master McGrath:

(taken from The Coursing Calendar, volume xxi).

Head – From tip of snout to joining on to neck, 9 and 1/2in.; girth of head between ears and eyes, 14in.; girth of snout, 7 and ½in.; distance between eyes, 2 1/4in.

Neck – Length from joining on of head to shoulders, 9in.; girth round neck, 13 3/4in.

Back – From neck to base of tail, 21in., length of tail, 17in.

Intermediate points – Length of loin from junction of last rib to hip-bone, 8in.; length from hip-bone to socket of thigh-joint, 5in.

Fore leg – From base of two middle nails to fetlock-joint, 2in., from fetlock-joint to elbow-joint, 12 1/4in., thickness of fore leg below the elbow, 6in.

Hind leg – From hock to stifle-joint, 9 3/4in., from stifle-joint to top of hip-bone, 12in., girth of ham part of thigh, 14in., thickness of second thigh below stifle, 8 1/4in.

Body – Girth round depth of chest, 26 1/2in., girth round loins, 17 1/4in., weight, 54lbs.

Master McGrath won 36 out of his 37 courses, winning £1,750 in four years (1867-1871). His fame was such that he was taken to Windsor Castle and presented to Queen Victoria. He was descended from the Bulldog-blooded King Cob (bred 1839).

“Master McGrath, as is well known, was a small dog, weighing generally, when he ran, about 54lbs. He was however, stoutly built, with good neck and shoulders, capital barrel, and rare legs and feet; he had a somewhat plain and short head, and a very short and fine tail. He was an example of what in-breeding will do from good strains, as he combined four strains of King Cob…three on his dam’s side and one on his sire’s.”

Thomas Jones in his The Courser’s Guide, 1896.

“I think I saw the immortal black run all his courses in public after his initial effort in his native land, and certainly no other greyhound ever made my blood tingle in the same way…During one of his courses, I was out in the running field…McGrath was driving closely…with marvellous movement, the entire length of his back being in visible play, just as though it were a mass of hingework…”

‘Vindex’ writing in the Irish Field, 1919.

“The Ibizan Hound is described as simply ‘slightly longer than tall’. The forechest or breastbone is sharply angled and prominent, however the Ibizan’s brisket is approximately 2 and a half inches above the elbow and the deepest part of the brisket is rearward of the elbow. The Ibizan’s front is entirely different from that of most Sighthounds, however in the field the Ibizan is as fast as the top hounds and without equal in agility, high jumping, and broad jumping ability.”

Robert W Cole writing in his most informative An Eye For A Dog, Dogwise Publishing USA, 2004.

“A feature of the Pharaoh Hound/Kelb tal-Fenek’s physique which it may have inherited from its putative (jackal) ancestors is its large, upstanding, triangular ears. The ears are remarkable, for they seem to be possessed of an independent life of their own. They are hardly ever still but always seem to be in movement, turning this way and that, often independently of each other, presumably tracking the sound of potential prey.”

Michael Rice, writing in his Swifter than the Arrow, The Golden Hunting Dogs of Ancient Egypt, Tauris, 2006.

“All coursing men pay particular attention to depth of chest, quality of back and loins, and still more to the hindquarters – i.e. the rump, the first and second thighs as well as the hock joints and pasterns. It is almost impossible to be too insistent regarding highly developed muscles and broad loins, where so much action is brought into play when a Greyhound is running and twisting after the hare.”

Frank Townend Barton MRCVS, in his Our Dogs, Jarrolds, 1938.