849 THE NEEDS OF THE HOUND

THE NEEDS OF THE HOUND

by David Hancock

No Hoof – No Horse

No Hoof – No Horse

"No hoof, no horse" is a time-honoured saying in equestrian circles but I've never heard a cry of "No foot, no dog" in canine circles. And when I see judging at KC-licensed dog shows, I find it rare indeed to see a judge check a dog's feet. But which is more important, sound feet or set of tail? I suppose in an arena where dogs are valued solely for what they look like rather than what they can do, this is not surprising. Ignoring the soundness of your dogs' feet is however a recipe for disaster in breeding programmes. Unless sound feet are produced, especially in sporting breeds, then the future of the domestic dog as an active animal is threatened. In his The Foxhound of the Future 0f 1953, CR Acton wrote: “There are still some kennels where the hounds stand on the sides of their feet and knuckle over at the knee, but most Masters to-day prefer the natural foot. The two extremes are the pre-war Belvoir foot and knee, and the Fell foot. They are usually referred to as ‘cat foot’ and ‘hare foot’ respectively, though both terms are stupid as each are essentially dogs’ feet.”

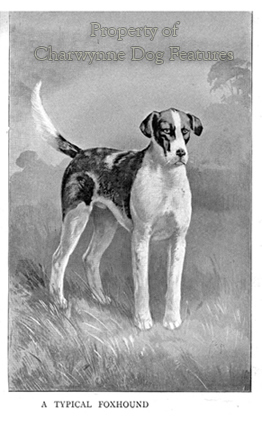

The most knowledgeable people on feet should be the Foxhound breeders. Whatever contemporary attitudes towards the sport of foxhunting, there is no doubt in my mind that the Foxhound is the best-bred dog in the country. In his book on the sport, referred to above, the renowned Lake District hound expert Richard Clapham wrote: "No matter what other good qualities a hound may possess, if his feet cannot stand wear and tear...his usefulness in life is therefore at an end." He went on to praise the hare foot or to him natural foot, claiming that the cat-like or club-foot needs more attention in kennels. He describes the hare foot as a fairly long, closely-knit, shallow-padded foot, similar to that of the wolf, coyote and fox. But the breed standard of hounds like the Rhodesian Ridgeback and the Otterhound calls for a round compact foot. The Basset Hound is required to have massive feet but be capable of great endurance in the field. Huge feet mean greater and longer contact with the ground and therefore more strain. No working hound benefits from massive feet.

Importance of Shape

The arguments over whether a round compact foot is preferable to the oval hare-foot in scenthounds have gone on for two centuries. In his contribution to The Lonsdale Library’s Deer, Hare & Otter Hunting of 1929, the Earl of Stradbroke, Master of the Henham Harriers, had this to say about feet and pasterns: “I have found that the hounds that last the longest, and go out on the greatest number of days in the season, are the lighter built hounds, often, too, those with what we all try to breed out, ‘hare-feet’!…I cannot help thinking that in advocating so strongly a short joint we go too far, and there should be a little more length, than is generally considered to be the perfection aimed at. Greater length gives the necessary elasticity to save a jar to the shoulder, when landing from a jump.” If, however, you look at the breed standards of the hound breeds, hunting by scent, recognized by the KC you find considerable variation between them. According to the KC, a Beagle’s feet must not be hare-footed; the Otterhound’s and the Foxhound’s feet have to be round; the Grand Bleu de Gascogne’s feet have to be long and oval; the Norwegian Elkhound’s feet have to be slightly oval; the Finnish Spitz’s feet need to be round; the Basset Bleu de Gascogne’s feet should be oval. No wonder the breeders of these breeds and those who judge them in the ring get confused by conflicting instructions.

Being Let Down

Stradbroke’s point about saving ‘a jar to the shoulder’ is a fair one; ramrod straight front legs, as seen from the side, lack spring and force-absorption; too short a pastern in the front legs restricts that essential springiness. The breed standards also insist that such breeds are well let-down at hock i.e. having their hocks close to the ground. This is an often misunderstood term; in both racehorses and sporting dogs, the seeking of long cannon bones led to the use of this expression. It was never intended to promote short rear pasterns but the promotion of long muscles in what in humans is the calf, leading to a low-placed hock or heel. In a different sense sporting dogs are being ‘let down’ by such advice in both cases set out above; elasticity is essential in the hound’s front legs and ample extension is vital in the hind-limbs. Over-compact feet, rounded and too tight, are in fact a handicap when the hound is striving to gain from ground pressure at pace, as users of the Fell Hound have long accepted. Some of the wording in the KC’s breed standards is ill-advised and judges are slavishly obeying them whereas they should be challenging them.

Harmful Desire

"The search for large bone is going to bring with it an obvious increase in growth rate which in turn renders the dog more liable to such problems as OCD, UAP or FCP..." Those words by the late Dr Malcom Willis in his authoritative Practical Genetics for Dog Breeders (Witherby, 1992) don't seem to impress dog-breeders perhaps as much as they should. Some breeds are actually prized for the weight of their bone, with many judges seeking heavy bone in exhibits, if their critiques are anything to go by. A century ago, Foxhound breeders lost their way and sought hounds with heavy dense massive bone, claiming that this feature provided stamina. They themselves however, when riding to hounds, rode hunters not cart-horses - and still managed to keep up! Their folly was subsequently exposed by a hound-expert from America, the legendary 'Ikey' Bell. It wasn’t until the late 1920s that the misguided passion for over-timbered legs, tightly-bunched toes and absurdly-compact feet was finally bred out in some packs of Foxhounds.

Breeders of horses know that 'good flat bone' provides the quality not masively thick bone. Breeders of Foxhounds have learned the importance of bone from past follies. The late Victorian/Edwardian Foxhound breeders, perhaps in a vain attempt to surpass the superlative light hounds of such as Lord Bentinck, unwisely opted for over-boned hounds. Daphne Moore, a Foxhound authority, in her book referred to above, described such hounds as 'built on massive lines, with great bone, barrel ribs, knuckling over knees, very short upright pasterns ending in a foot which was round, fleshy and often pigeon-toed.' I have previously pointed out how this was appropriately termed the 'shorthorn' period in hound breeding and thankfully it was soon abandoned. It was abandoned because it handicapped the hounds.

Needless Weight

The accomplished hound breeder Buchanan-Jardine gave the view, in his book referred to above, that 'Great weight of bone is unnecessary and rather a hindrance than the reverse...' It is of course the muscles that control the bones not the other way round; muscular development is far far more important than the thickness of the bone. It is a lazy response to state that 'what applies to Foxhounds doesn't apply to my breed'. The lessons learnt by any breeder in any field are worth heeding. To prize a dog mainly because of its weight is astonishingly naive. To boast of an unsound dog's shoulder height and poundage is, to me, a sure sign of an insecure personality needing to have his ego boosted by the size of his dog. To be proud of a sound big dog is surely, in the larger breeds, every good breeder's aim.

Identifying Need

Sadly, dog-breeding in purebred dogs is conducted, not on lines of desired and measurable improvement but on repeating the past, despite advances in scientific knowledge and a pronounced loss of type in some breeds. When, as part of my professional responsibilities, I ran a rare breeds' farm, I was able to benefit from a range of systems and recommended procedures, not utilised in adapted form by dog breeders. But even when breeding longhorn cattle, I never once heard the desirability of heavy bone mentioned in breeding programmes, and these were creatures weighing a ton and a half each. Strength and power in animals doesn't reside in bone size, as racehorses, antelopes and hyenas demonstrate only too vividly. A heavy hound such as the Fila Brasiliero can so easily become just that, rivaling our Mastiff for immobility, needless bulk and bone problems. At World Dog Shows I see substantial but athletic specimens in this breed and they are so impressive.

The Eyes Have It

If you find joy in watching a galloping Harrier scanning the foreground or an Otterhound focussing on suspected scent floating its way, before tensing up instinctively, you appreciate fully the close link between sight and scent in sporting breeds. These two particular senses have been highly developed in such breeds by man for centuries. Both senses mean more to dogs than to us; that alone is reason enough to prize them and strive to protect them. It is believed that dogs have 20/75 vision, meaning that they are able to see clearly an object from 20 feet away that a human with normal vision would see at 75 feet away. Cats have roughly 20/100 vision and horses 20/33, closer to ours. But dogs have vastly superior night vision and the detection of movement. They thrived as predators because of their combined better-developed senses of sight, hearing and smell. The low-light vision of dogs is greatly superior to ours too, facilitating hunting at night.

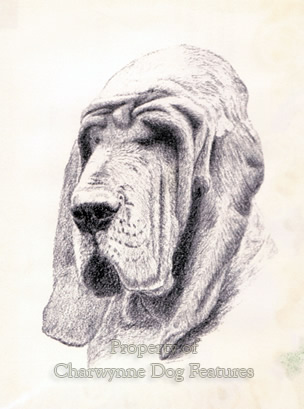

Dogs are more aware of events around them than human beings. Their eyes are set on their heads at a 20 degree angle, whereas we have our eyes set looking straight ahead. Dogs have a much wider field of view than we do, around 250 degrees against our 180 degrees. Perception of depth depends on binocular vision, which is the visual area where the two eyes overlap. The greater the binocular field, then the greater the depth of perception in a species. We excel in depth perception, with a visual overlap of around 140 degrees; dogs have a visual overlap of around 80 degrees only. They need all the help they can get in depth perception. By limiting further their binocular vision we increase their burden more than we realise. This additionally imposed limitation is one dogs could do without. Sunken eyes in the Bloodhound and red raw eyes in the Basset Hound are unwanted features.

Ear Examinations

The length of a dog's head is an inherited character that is almost as variable as the length of the dog's ears. Each breed has a relationship between the lengths of the dog's legs, its body, its head, its muzzle and its ears. Far better surely, in breed standards, to describe these proportions in relation to each other and the limits desired. In the standard of the Beagle, for example, the ears are required to extend to the nose tip. Overlong ears, getting longer with each generation, are of no benefit to the dog. Why not state that the Beagle's ears should extend to the nose but no further? Breeders and judges would then know that excessive ear length was frowned on in the standard. This was in fact the wording of the early breed standard and it was not wise to change it. It is just not good enough to state that a scenthound's ears should be "long" or "very long" or that they should extend at least to the hound's nose. Basset Hounds that step on their own ears are handicapped animals. There is a health handicap too in overlong ears. The thick, heavy, low-set ears cut off the circulation of air in the ear canal, thereby providing a breeding ground for bacteria and yeasts that cause chronic ear infections. A very hairy ear canal further restricts air circulation. Disappointingly, hair in the ear canal is not mentioned in any breed standard.

Seeking the Superfluous

Writing three centuries ago, Alexander Pope penned these prescient perceptive words: "Beauties in vain their pretty eyes may roll;

Charms strike the sight, but merit wins the soul."

Beauty does appeal to the eye and please the mind. But merit, real merit, that quality which justifies reward, does more, it lifts the spirit, satisfies the quest for high standards, truly 'wins the soul'. Beauty alone can never be enough, even at a dog show where physical perfection is aimed at, however impossible the task. When a handsome dog displays ugly movement it immediately ceases to be a beautiful dog to me. When a stunningly handsome dog reveals serious anatomical faults, on closer inspection, the charms that struck the sight soon trouble the mind. When you know that a strikingly good-looking dog carries hereditary flaws that will be passed on to its offspring, the mind should rebel and the soul take control. The beauty of a show exhibit, stacked for the judge's admiration, can be very temporary. Its genes and their accompanying faults and flaws are permanent.

The Danger from Fads

Fads may be passing indulgences for fanciers but they so often do lasting harm to breeds. If they did harm to the breeders who inflict them, rather than to the wretched dogs that suffer them, fads would be more tolerable and certainly more short-lived. But what are the comments of veterinary surgeons who have to treat the ill-effects of misguided fads? In his informative book The Anatomy of Dog Breeding, (Popular Dogs, 1962) vet and exhibitor, RH Smythe wrote: “In attempting to breed dogs which compare favourably with the standard laid down for any particular breed, we are guided by the aesthetic angle, and we completely disregard the fact that the majority of dogs are basically unsound or deformed, and that it is this fact which makes them valuable. We shall earn no marks if we succeed in lengthening the limbs of a Scottish Terrier or tightening the skin of a Bloodhound. Their beauty lies in their imperfections and we must maintain these if the breed is to retain its popularity.” This is an extremely outspoken honest statement from a most knowledgeable and experienced sportsman and exhibitor. We tend to condone past fads but need to be watchful about newly fashionable ones, often promoted to suit the plans of one influential kennel.

Breeders of British breeds are sometimes accused abroad of seeking exaggeration, exaggeration to a degree which is harmful and untypical. Those perpetuating our native breeds must remember the function for which that particular breed was developed, whether that function has lapsed or not. Only then can real genuine historically correct type be preserved. Every breeder of one of our native breeds has a special duty to safeguard its future; we must never let breeders from foreign countries change type or dictate what our breeds should look like. In his informative book The Theory and Practice of Breeding to Type, published by Our Dogs in 1952, CJ Davies concluded: "...animals nearest to the 'correct type' are those best adapted for the work which they are supposed to perform;" it is so important to remember this when assessing a dog or planning a litter. Breeders and judges, think hard before you make decisions - the future of all our magnificent breeds of dog are in your hands.

"The fads are to be ignored. So to ignore them may prevent one's winning with one's dogs under faddist judges while the fads endure but, in the long run, one will have better dogs and more success with them if one does not run after each showy and reasonless innovation that appears in one's breed. Such fads are liable to side-track the major purpose to breed logically constructed and well-balanced dogs."

From The Art of Breeding Better Dogs by Kyle Onstott, Denlinger, 1947.