784 GUNDOGS ON THE SCENT

Gundogs on the Scent

by David Hancock

“The subtle dog scours with sagacious nose

“The subtle dog scours with sagacious nose

Along the field, and snuffs each breeze that blows;

Against the wind he takes his prudent way,

While the strong gale directs him to his prey.

Now the warm scent assures the covey near;

He treads with caution, and he points with fear.

The fluttering coveys from the stubble rise,

And on swift wing divide the sounding skies;

The scatt’ring lead pursues the certain sight,

And death in thunder overtakes their flight.”

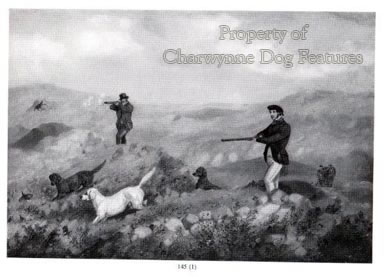

Those words of John Gay, the poet and dramatist, in his Rural Sports of 1711, one of the earliest mentions of wing shooting, convey neatly the sureness of sight in the human shooter and the singular skill of the gundog in locating its quarry using scent alone. Perhaps the greatest failing of man in his understanding of dog is his recurring inability to appreciate how dominant in the senses of the domestic dog is the sense of smell. For man the main detecting senses are sight and hearing, indeed I have read scientific papers claiming that our sixth sense only lapsed because of the high quality facility given to us by our eyes and ears. I have also read articles in field sports magazines extolling the superb eyesight of dogs, which I find hard to justify. I have never come across a dog with better all-round eyesight than man, although we will never be able to match their remarkable detection of movement. Never too will any of us ever match the quite astonishing sense of smell in dogs. If we wish to perpetuate real gundogs, we must ensure that we select for scenting power as an essential.

Nose Consciousness

The more perceptive writers on dogs have long appreciated the overriding importance of the canine sense of smell. Wilson Stephens in his quite excellent Gundog Sense and Sensibility has written: "To gundogs, with centuries of nose-consciousness bred into it, noses are for serious business, eyes merely come in useful occasionally"... going on to state that he had never needed to teach a dog to use its nose but usually had to teach one to mark the fall of game using its eyes.

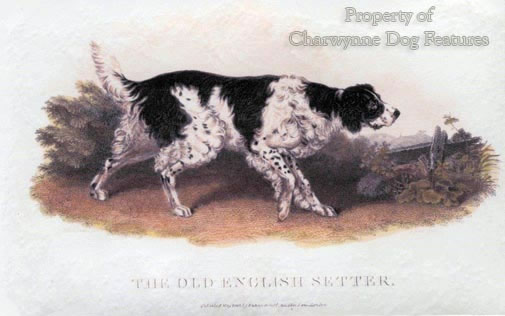

"Wildfowler" in his Dog Breaking of 1915 gave his list of setter qualities in this order; "Nose, pace, energy, style and indomitable endurance"...no doubt in his mind of the value to man of dog's sense of smell. But to limit scenting powers just to the nose is not entirely correct. In his informative The Mind of the Dog (1958), R.H.Smythe recorded this information: "Now, odours, scents or smells represent the delights of paradise to every dog...it is well known that delicate smells make the mouth water. Saliva dissolves the scent-bearing vapours and so the dog not only smells them but also tastes them. It is believed that hounds use both smell and taste, especially when the scent becomes strong, and it is believed by many that when hounds 'give tongue' they are actually savouring the delightful odour as it dissolves in their saliva." In pursuit of this belief our ancestors utilised the "shallow flew'd hound" to hunt by sight and scent, in that order, as a "fleethound" and the "deep-mouthed hound" as a specialist scenthound. No gundog should ever feature a short muzzle.

Trackers and Trailers

There is a link too between well-developed sinuses and the ability to track. The best trailers have the skull-conformation to allow good sinus development, adequate width of nostril and good length of foreface so that there is sufficient surface between the nostrils to house the smell-sensitive lining membrane. Scenthounds, gundogs and other hunting dogs depend on the shape of their skulls for their acute smell-discrimination. In pedigree breeds, the wording of the description of the skull in the breed standard can therefore directly influence the scenting prowess of the dog. The narrower skull of the terrier leads it to prefer to hunt by sight, show less interest in following a trail of scent yet, through selective breeding, show enormous interest in scent coming from below ground.

Mystery of Scent

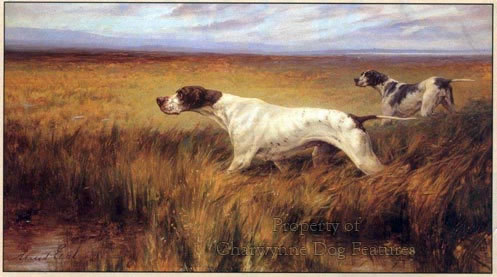

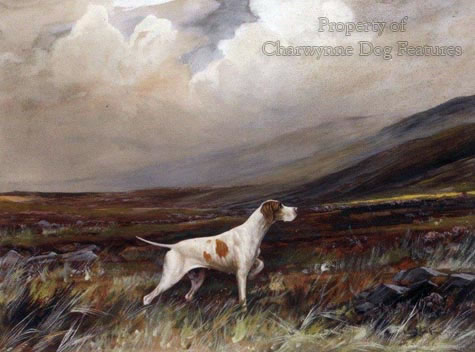

Imagine the delicacy of scent that allows a gundog, at some distance, to distinguish between a partridge and a lark, a pheasant and a woodcock. General Hutchinson, writing at the start of the 20th century, in his classic work Dog Breaking, advised hunting pointers and setters together, stating on the subject of scent that..."on certain days - in slight frost, for instance, - setters will recognise it better than pointers, and, on the other hand, that the nose of the latter will prove far superior after a long continuance of dry weather...” The different breeds often display definite strengths in such a way and so too do individual dogs.

Writing in his the Arte de Ballesteria y Monteria of 1644, Alonzo Martinez de Espinar noted, when using partridge dogs that: “On taking them to the field, one gets to know what they are, and whether they tend to seek the partridges by the foot-scent or by the body-scent…it must be insisted that they quest the partridges more by the body-scent than by the foot-scent, hunting them at first up-wind…that they may become body-scenters and not trackers; for there is a great difference between these two ways of seeking the birds.” He went on to list the ways in which bird-dogs hunt, preferring those that point and circle as well to those that simply circle. He favoured the natural ‘pointers of game’ because they disturbed the game the least. He rated nose and speed the foremost qualities in his dogs. He appreciated the subtleties of scent and the scenting capabilities of his partridge dogs.

No scientist has ever been able to explain satisfactorily the mysteries of scent in the hunting and shooting field. Scent is variously affected by the direction of the wind, heavy rain, freezing fog, high humidity, different crops, baking heat and the ground temperature. But no one has confidently stipulated the conditions needed for good scenting. HB Pollard observed, in his masterly The Mystery of Scent of 1929, drawing on Budgett’s Hunting by Scent, that 'scent is almost certain to be good between 3.30 and 4.30 after a warm October day, when the thermometer suddenly drops to near freezing point.' He then hastened to add: 'Under no other conditions would the writer care to back his opinion that scent will be good'! Not a lot of value there then! No wonder the scientists stay away! But if we do not select breeding stock on their scenting power as well as their other essential attributes, then we risk losing their greatest value to man.

“All shooting men know well that the deadly killing time for game is after 4pm. About this hour the air becomes cooler and moister; the dew commences to fall, and the birds to move; and the dogs hunt keener, because the scent lies. As a rule, the best scenting days are when scent rises. It is then that many dogs who generally carry their heads low will hunt high, to catch the taint which is borne and wafted away in the current of air. There is not the slightest doubt that scent rises or is depressed according to the atmospheric pressure; damp, rain, and other causes will affect it as well.”

Edward Laverack, writing in his The Setter, Longmans, Green, and Co., 1872.

“…scent is affected by causes into the nature of which none of us can penetrate. There is a contrariety in it that ever has puzzled, and apparently ever will puzzle, the most observant sportsman (whether a lover of the chase or gun) and therefore, in ignorance of the doubtless immutable, though to us, inexplicable, laws by which it is regulated, we are contented to call it ‘capricious’. Immediately before heavy rain thee frequently is none. It is undeniable that moisture will at one time destroy it, - at another bring it. That on certain days – in slight frost, for instance, - setters will recognise it better than pointers, and, on the other hand, that the nose of the latter will prove far superior after a long continuance of dry weather, and this even when the setter has been furnished with abundance of water, - which circumstance pleads in favour of hunting pointers and setters together.”

From Dog Breaking by General WN Hutchinson, John Murray, 1909.

“All gundogs rely on their noses more than their eyes when it comes to finding and retrieving game, but none of the breeds have had developed their sense of smell to the extent that it has been refined in pointers and setters. Again, this is down to the nature of the game: birddogs have to find game out in the open without flushing it, and this means they must locate their quarry at a sufficient distance to positively identify it before they close in to the point at which the birds decide that flight is a better alternative than concealment. And since they will be finding the quarry using scent alone – not sight, not sound, but scent only – it follows that one of the prime characteristics that the first breeders of birddogs will have selected for was scenting ability.”

From Working Pointers and Setters by David Hudson, Swan Hill Press, 2004.