775 THE WATER DOGS

THE WATER DOGS – ANCIENT BUT ANCESTRAL

by David Hancock

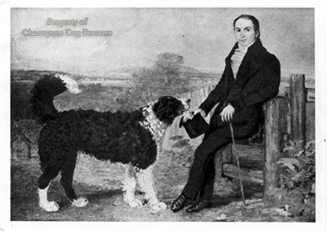

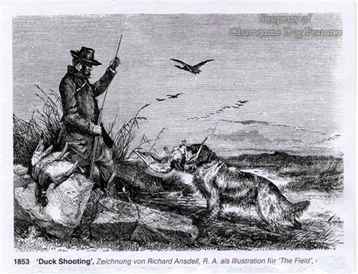

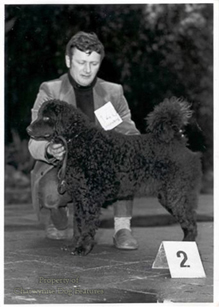

Function decided Type

Gundog breeds today are rightly revered and their sporting prowess as well as their breed type, which originated in function, perpetually prized. Sportsmen in early medieval times however knew the value of setting dogs and water dogs, the original retrievers, more than any of their successors. The invention of firearms did away with the need to recover arrows or bolts, as well as increasing the range at which game could be engaged. The setting dogs adapted from the net to the gun and survived, but the water dogs of Europe lost their value and many became ornamental dogs, like the Poodle. Some water dogs survive as breeds, with the Irish Water 'Spaniel' still causing discussion over whether it's a spaniel or a retriever. This type of dog, quite often black, liver or parti-coloured, had one physical feature which set it apart from most others, the texture of its coat. It is so easy when looking at a Standard Poodle in show clip to overlook their distinguished and ancient sporting history. And how many breeds recognised as gundogs can match their disease-free genotype? Anyone looking for a water retriever with instinctive skills, inherited prowess, a truly waterproof coat and freedom from faulty genes should look at the Standard Poodle, but stand by for ignorant comments from one-generation sportsmen, unaware of its heritage.

Living Examples

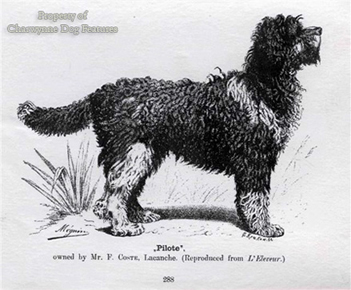

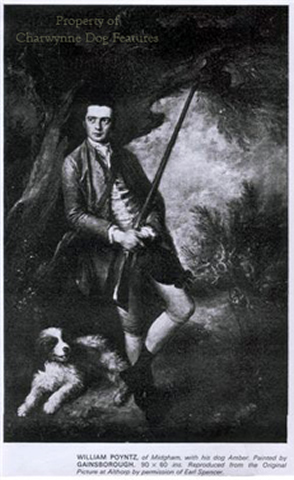

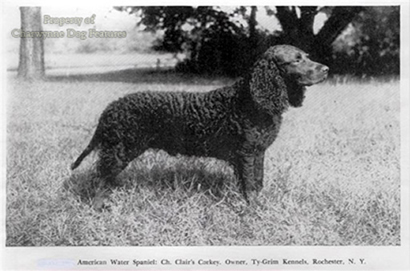

The Standard Poodle is a living example of the ancient waterdog whose blood is behind so many contemporary breeds: the Curly-coated Retriever, Wetterhoun of Holland, Portuguese and Spanish Waterdogs, Lagotto Romagnolo, Pudelpointer, Barbet, Irish and American Water Spaniels and the Boykin Spaniel. The distinctive French breed, the Epagneul de Pont-Audemer, has that water-dog look. The Tweed Water Spaniel was behind our hugely popular Golden Retriever. The old English Water Spaniel's coat sometimes emerges in purebred English Springers.

Ships’ Dogs

Ships’ Dogs

Not surprisingly such dogs were favoured by the sea-going fraternity, fishermen, sailors and traders. The dogs were trained to retrieve lines lost overboard and used as couriers between ships, in the Spanish Armada for example. In time, such dogs featured in the settlements established along the eastern sea-board of the New World by British, Portuguese, Dutch and French traders. Water-dogs exist today in those countries: the Barbet in France, the Wetterhoun in Holland, the Curly-coated Retriever and the Irish Water 'Spaniel' here and the Portuguese Water Dog there. The latter, still favoured by fishermen in the Algarve, has either a long harsh oily coat or a tighter curly coat. The Barbet has the long woolly coat, the Wetterhoun the curly coat.

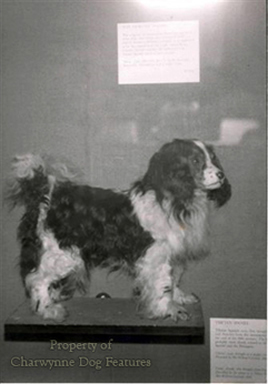

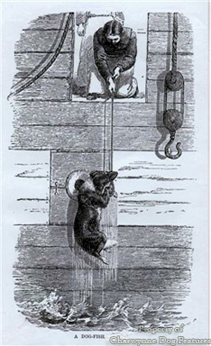

Fishing Dogs

Important historical information on ships’ dogs used as fishing dogs in the south of England can be found in the words of the 6th Earl of Malmesbury, when contributing to the booklet The Labrador Retriever Club’s A Celebration of 75 Years, published by the club in 1991. He wrote: “My great great grandfather needed a good retrieving water dog, and a companion in the home. He found both qualities in the little Newfoundlander (later to be renamed the Labrador, which was a less cumbersome name. How did these dogs develop their retrieving instinct? It was customary for the fishing boats in Newfoundland to carry dogs. These dogs developed their retrieving instinct in two distinct ways. Fish hooks were not as well made as they are today. A large fish, when brought to the surface, might free itself from the hook. A dog with a special harness would be lowered from the deck – grab the fish – and be hauled back on board with, hopefully, the fish still in its mouth…I know from my own experience that many of these dogs have still inherited this retrieving of fish.” Preserved in the Natural History Museum outpost at Tring is a ‘Trawler Spaniel’, a parti-coloured dog, just under a foot high, resembling the small sporting spaniels found here and on the Continent, often included by artists in family portraits.

Fishing Industry

The Earl went on to point out that when his ancestor was importing dogs from the Newfoundland Fishing Fleet unloading in Poole Harbour, the fishing industry in Christchurch and Bournemouth Harbours was intensive and the need for dogs extensive. Further north, the great retriever authority, Stanley O’Neill, recorded that his father was Superintendent of Grimsby Fish Docks, and he went with him to visit every port where fish was landed in England and Scotland, writing “I saw hundreds of water dogs around Grimsby and Yarmouth which were ships dogs, and it was well known that a cross with them to improve retrieving from water had been the origin of the curly-coats. In 1903, at Alnmouth, he saw men netting for salmon with a dog with a wavy or curly coat and of a tawny colour”. When he asked about the dog he was told it was a Tweed Water Spaniel. Such a dog was behind many of our emerging land retrievers, with what became the Golden Retriever, gaining from this type and coat colour. In his The Complete Farrier of 1815, Richard Lawrence wrote: “Along the rocky shores and dreadful declivities beyond the junction of the Tweed and the sea of Berwick, Water dogs have received an addition of strength from the experimental introductions of a cross with the Newfoundland dog…the liver-coloured is the most rapid of swimmers and the most eager in pursuit.” The genotype of the purebred Newfoundland incudes two different factors for the brown coat. Landseer Newfoundlands can be piebald red or bronze; the American vet Leon Whitney has reported both blues and reds and Clarence Little, the American coat-colour inheritance expert, has recorded the tan point pattern in pedigree Newfoundlands.

The Earl went on to point out that when his ancestor was importing dogs from the Newfoundland Fishing Fleet unloading in Poole Harbour, the fishing industry in Christchurch and Bournemouth Harbours was intensive and the need for dogs extensive. Further north, the great retriever authority, Stanley O’Neill, recorded that his father was Superintendent of Grimsby Fish Docks, and he went with him to visit every port where fish was landed in England and Scotland, writing “I saw hundreds of water dogs around Grimsby and Yarmouth which were ships dogs, and it was well known that a cross with them to improve retrieving from water had been the origin of the curly-coats. In 1903, at Alnmouth, he saw men netting for salmon with a dog with a wavy or curly coat and of a tawny colour”. When he asked about the dog he was told it was a Tweed Water Spaniel. Such a dog was behind many of our emerging land retrievers, with what became the Golden Retriever, gaining from this type and coat colour. In his The Complete Farrier of 1815, Richard Lawrence wrote: “Along the rocky shores and dreadful declivities beyond the junction of the Tweed and the sea of Berwick, Water dogs have received an addition of strength from the experimental introductions of a cross with the Newfoundland dog…the liver-coloured is the most rapid of swimmers and the most eager in pursuit.” The genotype of the purebred Newfoundland incudes two different factors for the brown coat. Landseer Newfoundlands can be piebald red or bronze; the American vet Leon Whitney has reported both blues and reds and Clarence Little, the American coat-colour inheritance expert, has recorded the tan point pattern in pedigree Newfoundlands.

Distinctive Coats

I have seen pure-bred Labradors featuring a tightly-curled coat and we have all seen English Springer Spaniels with very curly coats. I suspect the linty coat of the distinctive Bedlington Terrier owes its origin to water-dog blood, perhaps that of the Tweed Water Spaniel, once known in the area where the Bedlington was developed. The early Airedale Terriers, bred originally as waterside terriers in the Aire valley, had noticeably curly coats; this is now frowned on, the word crinkle-coated being preferred. The now extinct Llanidloes Setter featured this tight, densely-curled, waterproof coat. The Tweed Water Spaniel blood in the Golden Retriever is however not only acknowledged but prized. Our ancestors knew the value of water-dog blood.

The kennel clubs of the world have become seriously confused by the water dog breeds, regarding them as having different origins and functions, and therefore meriting different groupings. In Britain, our KC originally allocated the Spanish Water Dog and the Lagotto Romagnolo to the new sub-group of Utility Gundog – with the Kooikerhondje, within the Gundog Group, where they joined the Irish and American Water Spaniels. It places the Poodle in the Utility Group and the Portuguese Water Dog in the Working Group, with the Barbet, now becoming established here, awaiting allocation. From 2014 however, the Spanish Water Dog, The Lagotto Romagnolo and the Koikerhondje will be realloc ated to the Working Group. (But what kind of functional test could be designed for them there?) The FCI places the Water Dogs in their own sub-group, section 3 of Group 8 which embraces the retrievers and spaniels and includes the Barbet, possibly the most ancient water dog. They place the Irish and American Water Spaniels in this sub-group too. (The Poodle is grouped with the Toy breeds.) I agree with such a collection. It can however affect specialist knowledge amongst judges at shows held here and those on the continent of Europe.

ated to the Working Group. (But what kind of functional test could be designed for them there?) The FCI places the Water Dogs in their own sub-group, section 3 of Group 8 which embraces the retrievers and spaniels and includes the Barbet, possibly the most ancient water dog. They place the Irish and American Water Spaniels in this sub-group too. (The Poodle is grouped with the Toy breeds.) I agree with such a collection. It can however affect specialist knowledge amongst judges at shows held here and those on the continent of Europe.

It may not suit the misplaced pride of the shooting man of today to acknowledge the blood of poodle-like dogs in his working gundogs or associate such dogs with his sporting image. I see it as a matter of gratitude more than anything else. The liver and the black coat colours of the ancient water-dogs and their unique curly texture have survived and surfaced in many of today's breeds, whether sporting or non-sporting in use. Their fondness for and durability in water lives on too, whether the breed is linked to Ireland or Holland, Italy or Spain, France or Portugal, America or Britain. Water-dogs are the rootstock of many of our sporting breeds whether they have lost or retained the typical coat texture and colours of their distant ancestors. The water-dogs of Europe have contributed a great deal to our sporting heritage and more should be made of the debt we owe them, in breed histories for example. May those of Italy and Spain, now saved from extinction, go from strength to strength. And how about recreating our Tweed Water Spaniel?