767 THE BLOODHOUND

TRACKING THE BLOODHOUND

by David Hancock

Any spirited sportsman seeking a highly individual breed and one to challenge the world he lives in would be well-suited to the breed of Bloodhound! Writing on ‘The Bloodhound As A Sporting Dog’ in The Badminton Magazine of Sports and Pastimes of 1902, Russell Richardson gave the view “That the bloodhound fails to occupy the high position amongst sporting dogs to which, by reason of its high qualities, it would seem to be entitled…must be a matter of surprise and regret to all who have any personal knowledge of their capabilities…” In a world where conforming is all and copying others appears the name of the game, the sheer facial appeal alone of this breed should attract the individuals left among us. Richardson went on to express the pleasure to be obtained from ‘hunting the clean boot’ with such a dog, a pursuit that can surely antagonize no one. No doubt followers of the remaining Bloodhound packs still enjoying this pastime will echo his views.

Any spirited sportsman seeking a highly individual breed and one to challenge the world he lives in would be well-suited to the breed of Bloodhound! Writing on ‘The Bloodhound As A Sporting Dog’ in The Badminton Magazine of Sports and Pastimes of 1902, Russell Richardson gave the view “That the bloodhound fails to occupy the high position amongst sporting dogs to which, by reason of its high qualities, it would seem to be entitled…must be a matter of surprise and regret to all who have any personal knowledge of their capabilities…” In a world where conforming is all and copying others appears the name of the game, the sheer facial appeal alone of this breed should attract the individuals left among us. Richardson went on to express the pleasure to be obtained from ‘hunting the clean boot’ with such a dog, a pursuit that can surely antagonize no one. No doubt followers of the remaining Bloodhound packs still enjoying this pastime will echo his views.

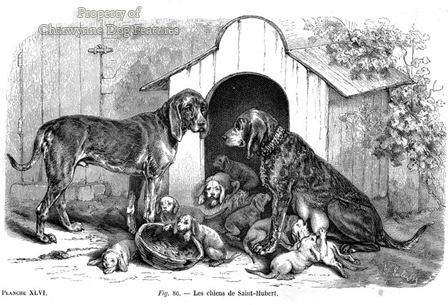

In its Illustrated Breed Standards the Kennel Club records: “The home country of the breed is Belgium and ancestry can be traced back to the monastery of St Hubert. In Belgium the Bloodhound is known by his other name of St Hubert Hound. It is most probable that this hound was one of those brought to England by the Normans in 1066.” Apart from the fact that Belgium did not become a country until 1830 and the hounds of the monastery were all-black, the great French hound expert of the nineteenth century, Count le Couteulx de Canteleu, held that all French hounds were descended from the St Hubert strain. The monastery is in the Ardennes, a region long famous for its schweisshunds but for black ones. The naming of the Bloodhound as the Chien de St Hubert, and the recognition of Belgium as its origin source, was done unilaterally by the FCI, the international kennel club based there. I think it is far more likely that the modern breed of Bloodhound was developed in Britain. The noun ‘bloodhound’ has been used loosely to describe hounds developed as far apart as Cuba and South Africa. The naming of breeds of dog has rarely been impressive.

In some ways, it might have been better for the breed to become our Sleuth Hound or Slough Hound, as the Scots would have it. The word ‘blood’ in its title conjures up images, for some, of a bloodthirsty attack dog rather than an amiable scenthound more interested in scent than taste! And the Bloodhound is the scenthound. In his treatise Of Englishe Dogges of 1576, Dr Caius wrote: ”For whether the beast, being wounded…and escapeth the hands of the huntsman; or whether the said beast being slain is conveyed cleanly out of the park (so that there be some signification of bloodshed) these dogs, with no less facility and easiness than avidity and greediness, can disclose and betray the same by smelling: applying to their pursuit, agility and nimbleness, without tediousness. For which consideration, of a singular speciality they deserve to be called Sanguinarii, Bloodhounds.”

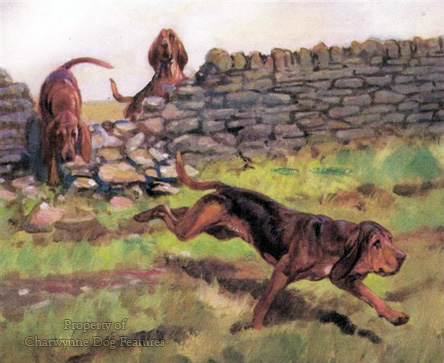

Historically, the Bloodhound was very much part of the chase, featuring in Landseer’s paintings of the deer hunt and their unique tracking skills leading to their use all over the world. The ‘father’ of the breed here was Edwin Brough, whose hounds were as much admired in the show ring as employed as scenters by a variety of users. His hounds were sound physically, lacking the super-elongated ears, excess of loose skin, distressing display of haw and over-abundance of dewlap/throatiness seen in the show-rings today. The pack Bloodhounds are much more like Brough’s hounds, yet, show breeders expressed outrage when some of the former were about to be admitted to the pedigree ranks to widen the gene pool. The obsession with pure breeding, even when to the detriment of a breed, is very 20th century and needs to be relegated to the hi story books. The blood of the Bloodhound was valued by our sporting ancestors when seeking to enhance the performance of other breeds.

story books. The blood of the Bloodhound was valued by our sporting ancestors when seeking to enhance the performance of other breeds.

The famous Foxhound Harlequin was one quarter Bloodhound and considered by the great hound expert of the 20th century, Sir John Buchanan-Jardine, as the best hound in the field he ever saw. Another great hound expert, Sir Newton Rycroft in Hounds, Hunting and Country, The Derrydale Press, 2001, wrote: “What is the potential value of such crosses both for fox- and deerhunting? Here I believe a very sharp distinction has to be made between pure bloodhound and working bloodhound with an outcross. When first considering the pure bloodhound, the best and, I believe, only the very best have retained the nose…As regards cry, stamina and constitution, I believe the pure bloodhound of today is far too weak to be a practical proposition for crossing.”

The American Leon Whitney, vet and sportsman, who probably bred more crossbred dogs than anyone before or since, wrote in his informative How to Breed Dogs, Orange Judd, 1947, lamenting the ‘rage for “bone”’ in the breed by show breeders, the strange desire for ‘heavy ankles’ and the desire for ‘heavy wrinkle’, contrasting the usefulness of such dogs with the much more workmanlike hounds produced by those breeding ‘trailers’. His remarks come to mind when you have seen say the Peak pack or the Coakham hounds and compared them to show Bloodhounds. Our Kennel Club is viewing needless exaggeration in breeds of dog with greater scrutiny nowadays. At the Richmond show of November 2011, one of the best show judges in Britain gave the view that this was the worst entry of the breed that she had ever judged, with some prizes being withheld. With tiny entry figures, some rosettes are hollow victories and I dread to think of some of the show dogs being bred from.

Against that background it seems a long time ago that the tracking Bloodhound Ledburn Boswell hunted his man twenty four hours cold over Corrie Common in Dumfriesshire before the Second World War and after that war, Mrs Oldfield’s hound won the Brough Cup for hunting a six-hour cold line for 3 miles in 20 minutes. In his Dog Breaking of 1909, General Hutchinson remarks on the value of this breed in tracking poachers: “…for the fear poachers naturally entertain of being tracked to their homes at dawn of day would more deter them from entering a cover than any dread of being assailed at night by the boldest armed party.” I give many marks to those stalwarts who still carry out tracking trials for their hounds and retain the famous scenting ability in these majestic animals. Scope for gamekeepers here!