762 THE ANATOMY FOR SPEED

The Anatomy for Speed

by David Hancock

Speed with Endurance

Speed with Endurance

The sighthound silhouette is unmistakeable: long legs, long back, long muzzle, it’s hardly surprising they are often called long dogs! But the pursuit of great pace creates the need for those features, with the requirement for endurance only just a secondary requirement. Foxhounds and huskies have great endurance but do not need immense speed; the sighthound build demonstrates the priority, it’s an anatomy for sheer pace, sustained pace but not for mile after mile, as the packhounds and the sled-dogs need. Of a Greyhound’s live weight, roughly 57% is accounted for by muscle. This compares with around 40% for most mammals. During exercise, a Greyhound can increase its packed (blood) cell volumes by between 60 and 70%, and increase its heart beat from below 100 to over 300 per minute; this allows a much more effective blood flow to its muscles than is the case in most other breeds. The Greyhound’s thigh muscles are far better developed than in most other breeds, facilitating pace.

Unique Build

The particular function of each sporting dog not surprisingly led to the development of the physique which allowed the dog to excel in that function. That is why sighthounds have a muscular light-boned build, the terriers a low-to-ground anatomy and the flock guardians substantial size. Sighthound breeds, wherever they were developed, project the same silhouette, display the same racy phenotype. The Azawakh of Mali, the Harehound of Circassia, the Sloughi of Morocco and the Tasy or Taigon from Mid-Asia would never change hands if they didn't look like fast-running dogs. If they didn't possess this anatomical design they couldn't function as speedsters.

Breed Differences

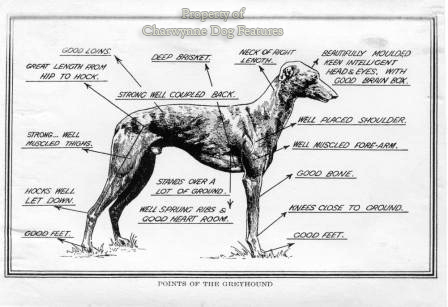

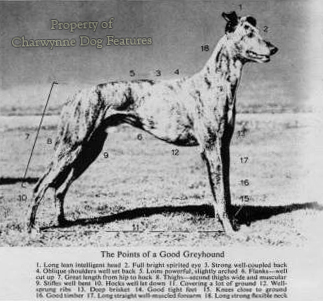

Whilst the sighthound breeds have a common silhouette, the differences in their hunting styles, hunting country and the local climate have produced small but key differences between the various breeds in the group. All need the long loin to provide flexibility in the fast gallop, a deep chest to enable lung power and immense propulsion from the rear. Sighthounds need length in the forearm to facilitate the fast double-suspension gallop. The Ibizan Hound has a different front from most of the sighthounds, designed to allow greater jumping agility. It displays a noticeable ‘hover’ in its gait. The Whippet has more tuck-up and loin-arch than the Mediterranean breeds. The Greyhound, from the side view, shows the anatomy its users have learned provides speed in the gallop. The shoulder blade is not as well laid-back as in say the ‘endurance’ breeds, like the sled-dogs, and the upper arm is more open than in a non-sporting breed, with a proportionately longer fore arm. The Greyhound’s front pasterns are long and sloping due to the immense ‘bend’ needed there at great pace. Many Saluki owners prefer the smaller, more energy-efficient type, since the breed is expected to cover substantial distances in the heat at the trot. The ratio of weight to height matters when speed with stamina is sought.

Weight Significance

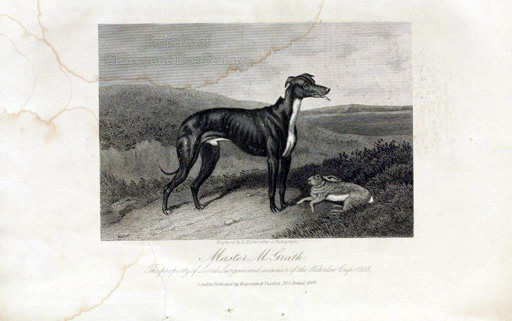

The weight of successful coursing Greyhounds is worth a glance. The renowned Master McGrath was around 53lbs, Bit of Fashion was 54lbs, Golden Seal, Staff Officer, Guards Brigade, White Collar and Fitz Fife were each around 65lbs but Shortcoming only 49lb. I believe that Coomassie was the smallest Greyhound that ever won the Waterloo Cup, weighing in at 44lbs. In 1881, a dog described as ‘very smart and clever’, Princess Dagmar, won the Waterloo Cup and was then considered to be a big bitch at 58lbs. The truly great track dog, Mick the Miller, was 64lbs at peak fitness. Our show Greyhound has no stipulation regarding weight but its ideal height, for a male dog, is desired at 28-30 inches. A Deerhound dog of 30 inches at the withers would weigh around 100lbs. Does a Greyhound need to be 30" high and approaching a hundredweight? At the end of the last century, the Waterloo Cup was twice won by dogs weighing over 90lbs; this has been put down to the Irish breeding for sheer speed in ‘park’coursing. The American KC standard sets the Greyhound's weight at 65-70lbs for a dog and 60-65lbs for a bitch. I don’t believe that the giant lurchers I see at some country shows would make effective hare-hunters, however fast in the short sprint.

Fit for Function

But I do see more correctly-constructed 'greyhound-lurchers' than I do show Greyhounds. This is a comment rather than a criticism, because I see many more of the former than the latter. It is worrying however to see a lack of muscle on show Greyhounds and at times a slab-sidedness which affects type as well as function. Sporting breeds must be judged in any ring on their ability to carry out their specific historic function, if not then there is really little point in breeding them. This ability was summed up by the esteemed ‘Stonehenge’, when writing on the Greyhound over a century ago: “This framework, then, of bones and muscles, when obtained of good form and proportions, is so gained towards our object; but still, without a good brain and nervous system to stimulate it to action, it is utterly useless; and without a good heart and lungs to carry on the circulation during its active employment, it will still fail us in our need.” Running dogs need heart in every sense.

Pace Based on Extension

The sighthound build is a superb combination of bone and muscle, a unique balance between size/weight and strength and quite remarkable coordination between fore and hind limbs. The Greyhound sprints in a series of leaps rather than running in a strict sense. It is what is termed a 'double-flight' runner, where the feet are all off the ground at the same moment. This is unlike a 'single-flight' animal like the horse which, when racing, nearly always has at least one foot on the ground. The Greyhound's leaping gait is rooted in quite exceptional extension, especially forward with the hind legs, but also rearwards with the front legs. Anatomically, the most vital elements in such a dog are the shoulders, and their placement, and the pelvic slope, which determines the forward extension of the all-important hindlimbs. That's where the power comes from. It always saddens me to see a sighthound in the show ring displaying upright shoulders and short upper arms, together with a lack of pelvic slope. It is even sadder when such an exhibit is placed by an ignorant judge! I see these faults being condoned at far too many championship dog shows.

Visible Power

One hundred and fifty years ago, in the early days of showing, running dogs were regularly exhibited: the winner of the Waterloo Cup in 1855, Judge, won second prize at the 1862 Islington conformation show. Twenty-five years later, Bit of Fashion, dam of the celebrated Fullerton, was exhibited at Newcastle, winning first prize. I find it hard to believe that a specialist Greyhound judge would not admire the powerful hindlimbs, strong sloping shoulders and rounder rib cage of the sporting type. All Greyhounds were once like this; where is the rationale of being attracted to a breed and then wishing to change its shape? Symmetry, gracefulness and beauty are not the essence of a sporting breed, however pleasing to the eye. Every Greyhound should demonstrate physical power, really look like a superlative canine hurdler – a genuine fast hunting dog.

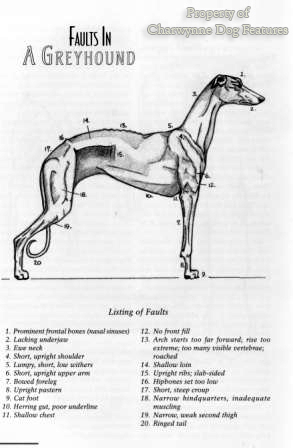

Physical Flaws

In The Kennel Gazette of July 1888, the Greyhound critique made mention of 'a showy black, but flat in ribs...' and a bitch of 'beautiful quality and style, but decidedly short of heart room...' Does 'showiness' compensate for flat ribs? Can a sighthound, designed to run very fast, combine beautiful quality with a lack of heart room? Five years later, a critique praised a 'niceish' black bitch with 'rather upright shoulders' (which came second!) and the reserve card winner a 'pretty' dog 'somewhat cow-hocked'. A critique on the breed just a year ago stated that front movement was really bad, with another observing that muscle tone was very hard to find. A recent Crufts critique on the breed commented on the absence of muscle tone and a lack of spring of rib in the entry. This is depressing.

Feet for Function

Ever since Dame Berners’s much-quoted description of a Grehound (sic) included the words ‘Fottyed lyke a catte’, the sighthound breeds’ foot has tended to be desired as ‘compact’, as in the Deerhound standard. The cat foot has been blurred with the compact foot. The Irish Wolfhound is expected to have round feet. The Borzoi is required to have hare-like rear feet and oval front feet. The Whippet needs oval feet. The Sloughi is preferred with the hare foot and I think this is right. I always associate the cat foot with endurance and the hare foot with speed. Condition can affect the appearance of the feet, with an unfit out-of-condition dog looking splay-footed and slack pasterned. In the dog the toe-pads do most of the footwork. The main difference between a hare foot and a cat foot is the length of the third digital bone. In both shapes of foot this bone should be parallel to the ground but the second digital bone in the cat foot should lie at 45 degrees. Exercise too can when carried out entirely on soft ground can cause the dog’s foot to look more spread out. Hunting country too can influence foot shape, with the Afghan Hound required to display large strong broad forefeet and long hindfeet, to suit the terrain it hunts over. ‘No foot, no dog’ is as applicable to the sighthound as is ‘no foot, no horse’ to that family of animals. But it is crucially important to appreciate that there is a fundamental difference between the locomotive system of the horse and that of the dog; the horse uses what is called the transverse gallop, the dog uses the rotary gallop. A veteran huntsman once gave me the view that ‘horses run with their legs, dogs with their backs.’

Superb Eyesight

Rotary gallop, muscular power, energy storage and soundness of feet apart, the speedsters of the dog world need superlative eyesight. Dogs easily outperform humans in detecting movement, their motion sensitivity allowing them to recognize a moving object from a distance of 800-900 metres away. Motionless, the same object will only be picked up by the dog’s vision at roughly half that distance. Dogs have far superior peripheral vision to us, around 250 degrees, against our 180 degrees maximum. It is no accident that all the cursorial breeds have the same skull outline. Their better depth perception and enhanced forward vision comes from longer nasal bones resulting from a longer nasal-growth period that occurs at an earlier age. As biologists Raymond and Lorna Coppinger point out in their perceptive book Dogs – A Startling New Understanding of Canine Origin, Behavior and Evolution of 2001, when selecting breeding stock for rabbit-catching hounds: “…I would sort through my dogs and pick those that worked best, and breed the best to the best. I might not realize that all I am really doing is selecting for longer nasal bones. The eyes themselves are no better than in any other breed. They are just in a better position to see forward.”

All animals active at night, whether predators or prey, have a ‘back-up’ visual support system, which gives the retina two opportunities to catch light, greatly enhancing night vision. A highly reflective layer of cells, the tapetum lucidum, underlies the retina and behaves like a mirror. Light is reflected back through the retina, the tapetum offering the photoreceptors a second chance to capture light. This mirror effect, reflecting light back out through the eye, makes predatory animals’ eyes shine in the darkness. Photographs of them pick this up. Dogs’ low-light vision is far superior to that of humans but is still not as good as the cat family, which detects light levels six times dimmer than our eyes can. Cross your coursing dog with a cheetah and you have the hunter by night as well as the hunter by sight!

Measurements of the coursing Greyhound Master M’Grath:

(taken from The Coursing Calendar, volume xxi).

Head – From tip of snout to joining on to neck, 9 and 1/2in.; girth of head between ears and eyes, 14in.; girth of snout, 7 and ½in.; distance between eyes, 2 1/4in.

Neck – Length from joining on of head to shoulders, 9in.; girth round neck, 13 3/4in.

Back – From neck to base of tail, 21in., length of tail, 17in.

Intermediate points – Length of loin from junction of last rib to hip-bone, 8in.; length from hip-bone to socket of thigh-joint, 5in.

Fore leg – From base of two middle nails to fetlock-joint, 2in., from fetlock-joint to elbow-joint, 12 1/4in., thickness of fore leg below the elbow, 6in.

Hind leg – From hock to stifle-joint, 9 3/4in., from stifle-joint to top of hip-bone, 12in., girth of ham part of thigh, 14in., thickness of second thigh below stifle, 8 1/4in.

Body – Girth round depth of chest, 26 1/2in., girth round loins, 17 1/4in., weight, 54lbs.

Master M’Grath won 36 out of his 37 courses, winning £1,750 in four years (1867-1871), a huge sum of money in those times.

“All coursing men pay particular attention to depth of chest, quality of back and loins, and still more to the hindquarters – i.e. the rump, the first and second thighs as well as the hock joints and pasterns. It is almost impossible to be too insistent regarding highly developed muscles and broad loins, where so much action is brought into play when a Greyhound is running and twisting after the hare.”

Frank Townend Barton MRCVS, in his Our Dogs, Jarrolds, 1938.