758 Lauding The Lakeland

LAUDING THE LAKELAND

by David Hancock

Today’s Lakeland Terrier represents the old rough-coated black and tan dog, with the undervalued Manchester Terrier representing the smooth variety. If you look at books devoted to terriers of a century ago, you could be forgiven for missing any references to the Lakeland Terrier. Darley Matheson’s Terriers of 1922 doesn’t list it and Pierce O’Conor’s Sporting Terriers a few years later only contains an illustration of “a working terrier from Lakeland” which resembles a Border Terrier. He gives no words on this breed but finds space for two paragraphs on the Otter Terrier, whilst admitting that it was probably extinct. But Hutchinson’s Dog Encyclopaedia of 1934 has 10 full pages on the Lakeland, including 18 photographs. A dozen years earlier, from thenames of Patterdale, Fell, the Coloured Terrier and the Elterwater Terriers, the breed title of Lakeland became accepted in the show ring, a breed club having been formed in 1912, with KC recognition being achieved in 1921, a year after the Border Terrier. Less than half a century later, a Lakeland Terrier went Best in Show at Crufts then Best in Show at the prestigious Westminster show in America the following year, some achievement.

Today’s Lakeland Terrier represents the old rough-coated black and tan dog, with the undervalued Manchester Terrier representing the smooth variety. If you look at books devoted to terriers of a century ago, you could be forgiven for missing any references to the Lakeland Terrier. Darley Matheson’s Terriers of 1922 doesn’t list it and Pierce O’Conor’s Sporting Terriers a few years later only contains an illustration of “a working terrier from Lakeland” which resembles a Border Terrier. He gives no words on this breed but finds space for two paragraphs on the Otter Terrier, whilst admitting that it was probably extinct. But Hutchinson’s Dog Encyclopaedia of 1934 has 10 full pages on the Lakeland, including 18 photographs. A dozen years earlier, from thenames of Patterdale, Fell, the Coloured Terrier and the Elterwater Terriers, the breed title of Lakeland became accepted in the show ring, a breed club having been formed in 1912, with KC recognition being achieved in 1921, a year after the Border Terrier. Less than half a century later, a Lakeland Terrier went Best in Show at Crufts then Best in Show at the prestigious Westminster show in America the following year, some achievement.

But how can you claim a distinct heritage for any terrier from the Lake District? In his The Book of Terriers of 1968, CGE Wimhurst wrote: “For many centuries the northern counties of England have been famous for the gameness and the working ability of the terriers bred there by hard-bitten breeders who cared not at all for appearance and whose estimation of a dog was based solely upon its prowess in the field. These terriers were known by a number of names, usually associated with the district in which they were bred – a custom which led to almost identical strains being known by different names. This tended to baffle the stranger visiting the north until, within comparatively recent times, clubs were formed and a common name for the breed chosen.”

Experts on northern terriers never gottoo worked up about breed titles. Richard Clapham, writing on Fox-Hunting in Lakeland, in The Lonsdale Library’s Volume VII, Fox-Hunting of 1930, set out this approach: “When speaking of fell hunting, mention must be made of the terriers, which are indispensable for bolting foxes from the rock-earths. Without them many a fox would have to be left that richly deserved killing. The terrier most suitable for work on the fellshould weigh from 15lb. to 16lb.; coat thick and wet-resisting; chest narrow, but not so much so as to impede the free action of heart and lungs; legs sufficiently long to enable the dog to travel above ground with ease to himself; teeth level, jaw strong but not too long; ears small and dropped close to the head, so that they are less likely to be torn by foxes. Most Lakeland terriers are of the so-called ‘Patterdale’ breed, with more or less Bedlington blood in them…Fell terriers have to follow the huntsman all day over rough going, perhaps in snow; thus they are better for being a bit on the leg.”

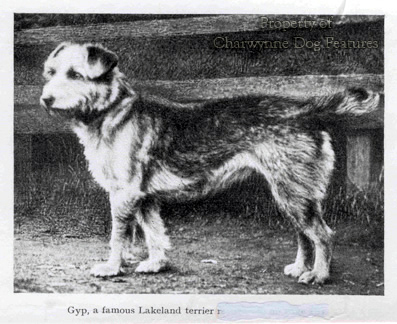

He uses name tags such as Patterdale, Fell and Lakeland without any attempt at precision, rightly concentrating on the anatomical needs of dogs used for such a purpose in such testing terrain. In his own book Foxes Foxhounds and Fox-Hunting, Clapham writes: “Some of the best all-round working terriers today are to be found with the fell foxhound in the Lake District…”,going on to point out the disadvantages to a working terrier there of being too short in the leg and back and too wide in front. He provides an illustration of a Lakeland Working Terrier ‘of the “Patterdale” breed, a leggy quite shaggy dog. Because he was writing quite soon after the Lakeland Terrier became recognised by the Kennel Club, he stressed the limitations of show-bred dogs. But to be fair to this breed, it has been less spoiled by show ring glamour than most other sporting terrier breeds, with some exhibitors working their dogs too.

But it is worrying to see critiques from show ring judges that read: “Rear movement in some animals was a real cause for concern. I doubt they would last a day on the fell…surely this is the most basic of requirements for a Lakeland. Shoulder placements in some exhibits left a lot to be desired.”A terrier in the fells with no power from behind and limited flexibility in front is going to get trapped underground fairly regularly. Luckily, this breed has attracted some gifted devoted breeders: Eric Dodgson who with David Read started the outstanding N’Beck line of working Lakelands in Egremont, subsequently blended with and contributing to lines from Cyril Tyson, John Cowen, Edmund Porter and the pedigree kennel of Alan Johnston (Oregill). An important line was started by Fred Barker, for use with his Pennine Foxhounds, a strain started in the early part of the 20th century and famous for a strong-headed, very powe rful dog, ‘Rock’, who passed on the ‘brick-head’ to his progeny. More recently, the Lakelands of Gary Middleton of Kendal have won a deservedly high reputation. Meeting some overseas breed enthusiasts at a World Dog Show a decade ago, I found that they only really wanted to discuss the Barker strain, saying this was the blood they coveted – and they were show people!

rful dog, ‘Rock’, who passed on the ‘brick-head’ to his progeny. More recently, the Lakelands of Gary Middleton of Kendal have won a deservedly high reputation. Meeting some overseas breed enthusiasts at a World Dog Show a decade ago, I found that they only really wanted to discuss the Barker strain, saying this was the blood they coveted – and they were show people!

It is unwise to speculate on the original sources of terrier breeds, terriers from Ireland moved around England with travelling workers, terriers from England were regularly introduced into Ireland by soldiers in the garrisons there. Fred Barker started off with his red Fell Terrier Chowt (chewed) Face Rock and two white terriers of Russell type, bred by the Ilfracombe Badger Digging Club. Welsh Terrier blood was also used in the early days of the Lakeland as a breed. The Bedlington infusions have been mentioned too by many researchers. The fact remains that, whatever blood is behind the modern breed of Lakeland Terrier, it has been blended quite brilliantly to produce the much-admired breed of today. Long may it prosper!