743 WORKING THE WELSH TERRIER

WORKING THE WELSH TERRIER

by David Hancock

“Will he be a Welsh Terrier if he is to be like a Fox Terrier…We have too many Fox Terriers already. Let the poor Welshman have his native terrier on different lines, if you please…I think the time has come for all gentlemen selected as judges to be able to distinguish the great difference between the Welsh terrier proper and the so-called, viz., the Black and Tan Wire-Haired terrier.”

“Will he be a Welsh Terrier if he is to be like a Fox Terrier…We have too many Fox Terriers already. Let the poor Welshman have his native terrier on different lines, if you please…I think the time has come for all gentlemen selected as judges to be able to distinguish the great difference between the Welsh terrier proper and the so-called, viz., the Black and Tan Wire-Haired terrier.”

Writer calling himself “Native Terrier” in The Kennel Gazette, February, 1891.

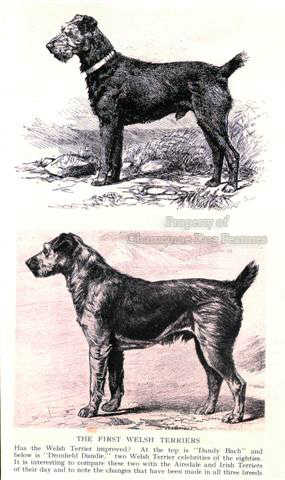

At the Bangor Show of 1885, a group of Welsh Terrier fanciers decided to approach the Kennel Club with a view to having their dogs registered as such. But the north of England breeders of similar dogs wished their rights to be acknowledged too. So, in November 1885, to satisfy both parties the KC agreed to enter in the Stud Book the classification 'Welsh Terrier or the Old English wire-haired Black and Tan Terrier Class 53'. Later, the fanciers of the English dogs failed to form a club and in time any reference to English terriers was deleted in registration and show documents. At a meeting of the Welsh Terrier Club in February 1890, the motion ‘That no dog or bitch the sire or dam of which is a Fox, Irish, Airedale or Old English terrier shall be eligible to compete at any show…’ was only narrowly defeated.

In October 1890, a Welsh Terrier stud dog was advertised in The Kennel Gazette as ‘best-headed, perfect in coat and colour, best legs and feet, has a beautiful small ear, perfectly carried, is free from white; his only fault, by some judges: a trifle too big. Will not serve Irish or Fox-terrier bitches.’ Such words would be both needless and unthinkable today, even if such an outcross were to be to the benefit of a sounder dog in any breed of terrier. I can understand the temporary short-term need to establish breed type in an emergent breed at that time. Over a century later, that long-sustained closed gene pool is not the best way to produce the healthiest physically-soundest sporting terrier; breed purity ahead of health and vigour is not only unwise but a form of calculated breed harmfulness, knowingly inflicted. In The Kennel Gazette of 1888, LPC Astley, an experienced sporting dog judge, wrote: “To my mind, the domed skull, low set ears, and large eyes of the Welsh terriers proper must certainly be improved by a judicious cross of the undoubtedly better-headed terriers of the north and centre of England.” He was seeking a better dog not a cravenly perpetuated breed.

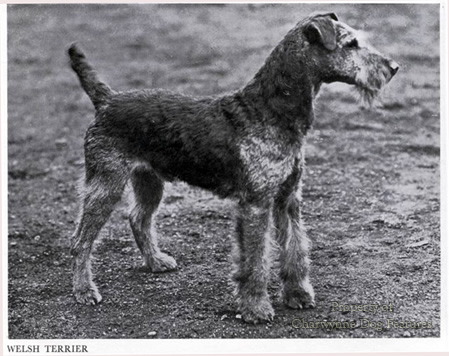

In his The Complete Book of the Dog of 1922, Robert Leighton, himself a terrier judge, wrote on the breed: “The specimens which were first shown were, as may be imagined, not a very high-class-looking lot. Although the breed had been kept pure, no care had been taken in the culture of it, except which was necessary to produce a game sporting terrier, able to do its work…naturally enough, good shoulders, sound hind-quarters, more than fair legs and feet, and excellent jackets were to be found in abundance…” He then went on to fault just the heads on offer! I am not suggesting that heads are not important but just look at the merits he listed, many of which have been lost in the pedigree breed of today! So much for the ‘culture’ of the breed!

The Welsh Terrier has long had a loyal show following, with around 250 registered in 1908, 1960 and 2000, rising to 337 in 2009. This appealing breed exemplifies the old rough-coated black and tan terrier once found all over Britain; England could well have claimed the type as hers too. Bigger than a Lakeland and smaller than an Airedale, the Welsh Terrier makes up in character what it lacks in physical identity. Once accused of being a wire-haired Fox Terrier in a different jacket, there have been accusations too of infusion of the latter's blood in this Welsh dog's development. The silhouette is markedly similar. It was argued that the old Welsh Terrier had a Chippendale front, poor shoulders, a big coarse apple head and big round bold eyes. The infusion of Fox Terrier blood allegedly produced a smarter-looking terrier but also introduced the long muzzled head. Robert Killick, a distinguished breeder of Welsh Terriers, recently commented ‘After more than ten years in Welsh Terriers (my only breed) the result of a mating between my own three generation bitch and my own four generation dog produced a litter of three Wire Fox Terriers (and fine specimens) and one Welsh Terrier.’ Past out-crossings whether covert or overt so often reveal themselves.

The later recognition of the smaller Lakeland Terrier undoubtedly drew devotees of the English black and tan terriers with the Lakeland earning KC recognition in 1921. But 'Working Welsh' terriers of a separate type were still favoured. Writing in Compton’s The Twentieth Century Dog of 1904, the Rev WP Nock recorded: “The terriers are much too big, and many that are winning today are too red in colour and too long in body. In my opinion, too much is sacrificed for long heads, which are fox terrier heads, and are thus going away from the true old Welsh type.” In the same publication, WS Glynn was writing: “In body formation and limbs he must be symmetrical; he must not be, as so many fox terriers are, all ‘front’, and possessed of nothing behind the saddle fit to carry a mouse.” Time and time again, down the years, the influence of the Fox Terrier, as designed in the late nineteenth century, is regretted in so many terrier breeds. The unwise tendency in this breed to produce too long a head and too straight a front has been aped by other terrier breed fanciers too, to the loss of true type in their breeds, but now considered the real breed type by copy-cat exhibitors, anxious to perpetuate consensual thinking. It is time for some honest revision.

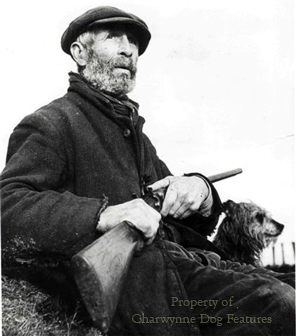

Until sixty years ago, two kennels still bred Welsh black and tan working terriers: the Ynysfor Otterhounds and the Glasnevin Foxhound pack. The former were kept free of KC-registered Welsh Terrier blood, being smaller, 14lb, 13", box-headed dogs, much more like Fell Terriers. Inter-breeding has probably contributed to the muted tan of the Lakeland being replaced all too often by the fiery red-tan of the Welsh dogs. The Welsh Terrier has been described as the terrier giving the maximum of pleasure with a minimum amount of trouble, but some terrier-men feel that they lack tenacity and committed prey-drive. Show critiques of recent years make disappointing reading, ranging from '...the quality of the breed has sadly deteriorated...' to '...this breed is deteriorating in both quality and movement...' This is an attractive breed with a sound working provenance from its distant past, one deserving attention.

It would be an enormous pity if the Welsh Terrier slowly disappeared not just from public view but from the working role too. It is shaming that French sportsmen practising their ‘venerie sous terre’ are using working Welsh Terriers in packs on fox and coypu, proudly parading them at their equivalent of our Game Fair, complete with terrier-pouches, spades and pick-axes. They arouse the admiration of every visiting British sportsman. It now needs a few patriotic Welshmen to rally to the cause and perpetuate the selfless work done by the pioneers in each breed. We lost the Welsh Setter; let's keep the Welsh Terrier – and as a worker not just an exhibit!

“In conclusion I would congratulate breeders on the great strides made in head properties and in uniformity of type, on the material reduction of undershot specimens, and especially on the wonderful coats one sees on these terriers. In this last particular I do not know a variety of terrier living that can touch the Welsh Terrier, i.e. for a good hard workman-like coat; but I would urge upon them the necessity of breeding better bitches, of breeding to the standard weight, and of continuing to keep clear of the Fox Terrier cum Hound cum Collie type.”

Walter S Glynn in The Kennel Gazette of January, 1893.