734 IRISH SIGHTHOUNDS

IRISH SIGHTHOUNDS: THEIR WOLFDOGS

by David Hancock

Huge shaggy-coated hunting dogs were once widely used by the Celts in their central European homeland in the eighth century BC and these accompanied them on their migrations to Britain, Ireland and Northern Spain from the fifth to the first century BC. In his Gentleman's Recreation of 1675, Nicholas Cox wrote: "Although we have no wolves in England at the present, yet it is certain that heretofore we had routs of them, as they have to this very day in Ireland; and in that country are bred a race of greyhounds which are commonly called wolfdogs, which are strong, fleet and bear a natural enmity to the wolf. Now in these greyhounds of that nation there is an incredible force and boldness..."

Huge shaggy-coated hunting dogs were once widely used by the Celts in their central European homeland in the eighth century BC and these accompanied them on their migrations to Britain, Ireland and Northern Spain from the fifth to the first century BC. In his Gentleman's Recreation of 1675, Nicholas Cox wrote: "Although we have no wolves in England at the present, yet it is certain that heretofore we had routs of them, as they have to this very day in Ireland; and in that country are bred a race of greyhounds which are commonly called wolfdogs, which are strong, fleet and bear a natural enmity to the wolf. Now in these greyhounds of that nation there is an incredible force and boldness..."

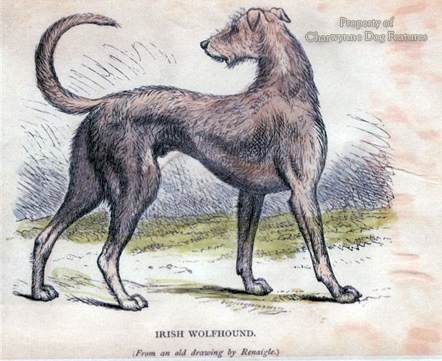

Behind the Irish Wolfhound there are at least three distinct types: Just over one hundred years ago, Fitzinger identified "...The Irish Greyhound, next to the Indian and Russian Greyhound, is the largest specimen of the greyhound type, combining the speed of the Greyhound with the size of the Mastiff. The second type is the Irish coursing dog, a cross between the Irish Greyhound and the Mastiff or bandogge. He is shorter in the neck, with a coarser skull, broader chest and heavily flewed lips. " The third variety he described as a cross between the Irish Greyhound and the shepherd dog, being low on the leg and having a shaggy coat. The latter sounds like a shepherd's mastiff or native flock guardian, a bigger version of the Irish Beardie or hirsel. Perhaps the Beardie type lurcher of today is the modern counterpart.

Lord Altamont wrote to the Linnaean Society in 1800 to state that: "There were formerly in Ireland two kinds of wolfdogs - the greyhound and the mastiff. Till within these two years I was possessed of both kinds, perfectly distinct, and easily known from each other. The heads were not so sharp in the latter as the former; but there seemed a great similarity in temper and disposition, both being harmless and indolent." He stated that the painting held by the Society was of the mastiff wolfdog; it was 28 inches at the shoulder. The word mastiff as used here indicated a type not a breed.

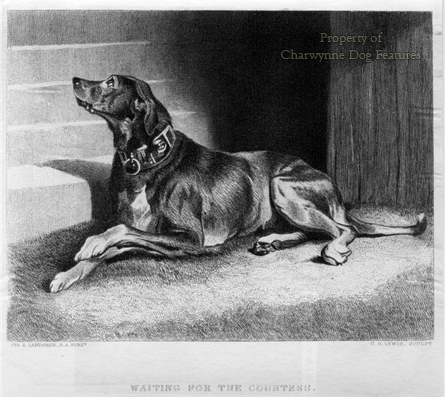

The Countess of Blessington in Ireland was presented with a giant Suliot Dog by the King of Naples. Lady Blessington was one of the Powers of Kilfane, who at one time were the only people who patronised the Irish Wolfhound. Suliot Dogs came from Epirus in Greece, location of the Molossian people, and were giant hounds, used as outpost sentries in the Austrian Army and as 'parade dogs' or mascots of German regiments. They were used to give added stature to German boarhounds (the hunting dogs being nearer to 26 inches at the shoulder than the 30 inches minimum of today's Great Danes). Lady Blessington's Suliot Dog is likely to have been used as a sire at Kilfane; it was an imposing specimen.

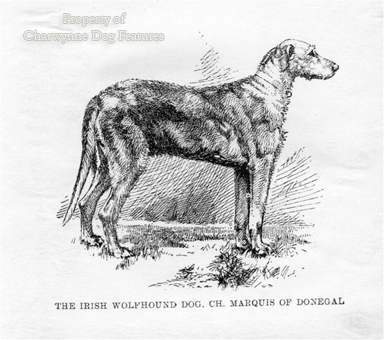

The Irish Wolfhound was all but lost to us in the latter half of the 19th century. Then, in 1863, an Englishman, Captain George Augustus Graham, a Deerhound breeder, noted that some of his stock threw back to the larger type of Irish Wolfhound. He obtained dogs of the Kilfane and Ballytobin strains, the only suitable blood available in Ireland at that time. He then interbred these with Glengarry Deerhounds, which had Irish Wolfhound blood in their own ancestry. In due course he produced and then stabilised the type of Irish Wolfhound which he believed to be historically correct. Outcrossing continued, with Capt Graham using the blood of a 'great dog of Tibet', then, between 1885 and 1900, seven Great Dane crosses were conducted, and Borzoi blood used several times in the 1890s. This is of course how all hunting dogs were once bred, good dog to good dog, irrespective of breed titles. Closed gene pools are very much a modern phenomenon; they so often conflict with the sportsman’s needs.

Our contemporary sympathy for the wolf would not have been shared by those living in remote villages in India or a number of European countries in the middle ages. Wolves, operating in packs, threatened livestock and sought human prey when desperate for food. Powerful dogs of the flock guarding type were needed to protect livestock and strong-headed very fast hounds were needed to course them. Hunting wolves for sport may not appeal to 21st century sympathies, but that should not lessen our admiration for wolfhounds, their bravery and athleticism in the hunt, when wolf numbers required checking.

Against that background, it is surely important for us to respect past function, which bequeathed us the wolfhound breeds, and breed to reflect that heritage. Borzois bred purely for beauty of form and Irish Wolfhounds bred mainly for shoulder height shows little respect for their distinguished past service to man and little regard for historical honesty. It is sad to read, in show critiques on Irish Wolfhounds, such judges's comments as these: "I was very shocked at the terrible soft condition of some of the hounds..." "Movement should be a cause for concern, both for breeders and owners...Many hounds lacked strength and muscle particularly in hindquarters..." "...the most prevalent fault in the entry was deviation from true in front action." The wolfhounds of Ireland are extraordinary hounds; their past courage and athleticism deserves our respect. They were never intended to be ornaments or fashion accessories; they survived combat with serious adversaries and then the whims of man, long may they flourish.