733 RUSSIAN SIGHTHOUNDS

RUSSIAN SIGHTHOUNDS

by David Hancock

If the Saluki is the canine aristocrat of the desert and the Afghan Hound that of the mountains, then the Borzoi, and its sister breeds of southern Asia, is the canine aristocrat of the steppes. All too often we associate the hunting Borzoi with snowy forests and the wolf habitat but the finest hunting ground for the Russian sighthounds will forever be the steppes. The new meritocracy in Russia seems to be reviving the hunting Borzoi, as national pride in their sporting past re-asserts itself. We know little of the Chortaj or West Russian Coursing Hound or Eastern Greyhound and the Steppe Borzoi or South Russian Steppe Hound, both smooth-coated 26" sighthounds.

If the Saluki is the canine aristocrat of the desert and the Afghan Hound that of the mountains, then the Borzoi, and its sister breeds of southern Asia, is the canine aristocrat of the steppes. All too often we associate the hunting Borzoi with snowy forests and the wolf habitat but the finest hunting ground for the Russian sighthounds will forever be the steppes. The new meritocracy in Russia seems to be reviving the hunting Borzoi, as national pride in their sporting past re-asserts itself. We know little of the Chortaj or West Russian Coursing Hound or Eastern Greyhound and the Steppe Borzoi or South Russian Steppe Hound, both smooth-coated 26" sighthounds.

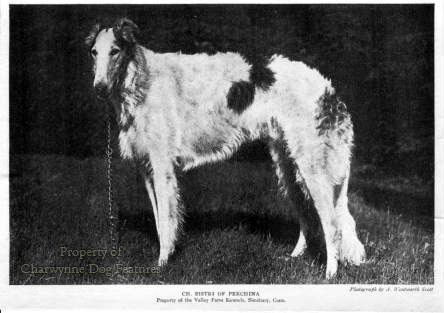

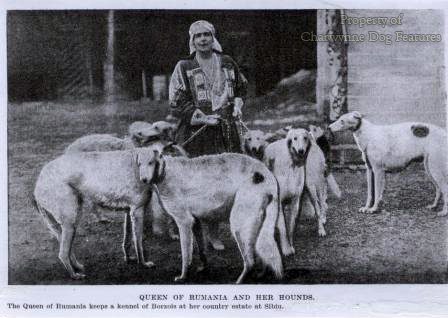

The longer-haired Russian Wolfhound or Borzoi, championed by the Tsars and lionised by writers such as Turgenev and Tolstoi, was patronised here initially by the nobility and has maintained popularity without finding a field use. I did once learn of one being used, devastatingly, on fox in Scotland however. Behind the modern single breed of Russian Borzoi, there are barrel-chested Caucasian Borzoi, huge curly-haired Courtland Borzoi and bigger-boned Crimean dogs. This type was found as far west as Albania too. The Kennel Club Borzoi is now confined by a closed gene pool, in the rigid pursuit of purity rather than performance, but the lesser known Borzoi types are really South Russian lurchers both in employment and in breeding method. Hungry peasants and level-headed kulaks didn't keep hounds because they were pretty!

Although the Russian wolfhound is known to kennel clubs around the world as the Borzoi, the word itself means light, swift and agile, being used rather loosely just as greyhound was in Britain, levrier in France and windhund in Germany. The Borzoi was more commonly used for fox and hare coursing and the Russians once referred to Asiatic, Polish (Chart or Chort), Crimean or Tartar Borzoi (these more like Salukis) and the Circassian variety too. The Scottish Greyhound (Deerhound) was used on wolves and other quarry, coursing hounds having long been used in a wide variety of pursuits. It is easy to forget when looking at contemporary breeds that their ancestors did not breed true to type, being judged solely on performance, not on conformation to a set standard. Behind the modern single breed of Russian Borzoi, there are barrel-chested Caucasian Borzoi, huge curly-haired Courtland Borzoi and bigger-boned Crimean dogs. This type was found as far west as Albania too.

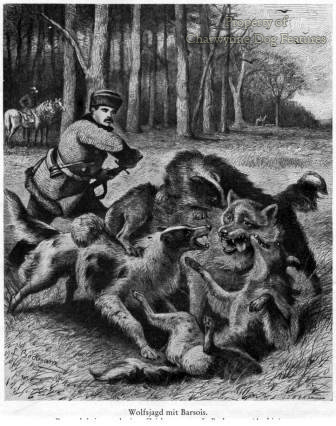

The graceful athletic build of the Russian wolfhound has long drawn widespread admiration: Charles Darwin described them as an 'embodiment of symmetry and beauty'. Undoubtedly the attractive silky coat of the modern pedigree Borzoi enhances its physical appearance. But as with the Saluki and the Ibizan hound, of this type of swift hound, there were varieties of coat in the Borzoi too. The Hunter's Calendar and Reference Book, published in Moscow in 1892, divided the Borzoi into four groups. First, Russian or Psovoy Borzoi, more or less long-coated; second, Asiatic, with pendant ears; third, Hortoy, smooth-coated and fourth, the Brudastoy, stiff-coated or wire-haired. But whether the hounds were sleek or bristle-haired, wolf coursing in Russia before the Revolution was what fox-hunting was to Britain and par force hunting was to France.

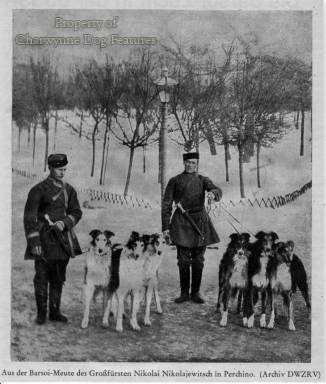

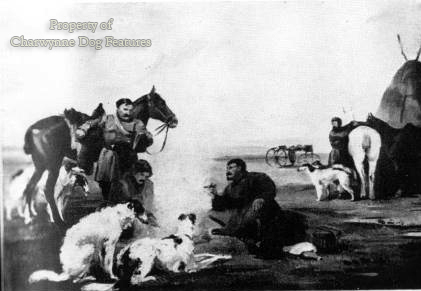

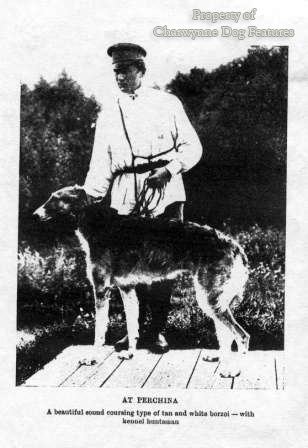

As Leo Tolstoi recorded in War and Peace: "Fifty-four coursing hounds were taken with six mounted horsemen and keepers of hounds. Apart from the Master and his guests, another eight huntsmen took part, with more than forty hounds. In the end, there were one hundred and thirty hounds and twenty horsemen in the field." Tsar Peter II kept a pack consisting of 200 coursing hounds and over 420 Greyhounds. Prince Somzonov of Smolensk had 1,000 hounds at his hunting box, calling himself Russia's Prime Huntsman. Better known was the hunt with the Perchino hounds near Tula on the river Upa, where Archduke Nicolai Nikolsevich established a hunting box in 1887 and hunted two packs of 120 par force hounds, 120 to 150 Borzoi and 15 English Greyhounds. To ensure sufficient hardiness for winter wolf hunts, both horses and hounds were kept in unheated stables or kennels.

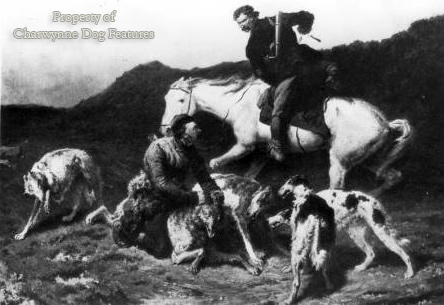

Hunting from sledges sometimes took place from October, with mounted beaters putting up the wolves, which were often fed to keep them in the hunting grounds. In the Perchino game reserve, between 1887 and 1913, 681 wolves were killed, as well as 743 foxes, 4,630 brown hares and 4,026 white hares; Borzois obtaining the bulk of this bag. Whatever the rights and wrongs of hunting on such a scale, the robustness, fitness and stamina of the hounds must have been remarkable. Coursing with Borzois in Tsarist Russia called for a high standard of horsemanship and superbly-trained hounds. Each mounted handler rode with his three hounds on long leashes, slipping the hounds whenever a wolf was either put up by the extended line of mounted beaters or flushed out of the woods by scent hounds of the Gontchaja type. Many of us would find it difficult enough to control three Borzois on short leashes whilst dismounted!

The Borzoi is still important for the Russian fur trade, for they catch foxes without mauling them and ruining their pelts. This also avoids the crueller use of iron spring traps. Usually 20 leashes of Borzois were taken to a hunt, each consisting of two males and a bitch. The hunting season was summer coursing (June to early August) on hare or fox, then summer training for Borzois in August. This consisted of 20 kilometres walking or trotting with the hunt horses, followed by advanced training on captive wolves in early September, then the wolf-coursing season from mid-September to the end of October. But the real all-round 'hunting by speed' field dogs from Russia are the mid-Asiatic Tasy or East Russian Coursing Hound and the Taigan or Kirghiz Borzoi. The Circassian Greyhound, also known as the Crimean, Caucasian or Tartary Greyhound, is more Saluki-like, understandably so, as the Circassians could be found as far afield as Syria and Iraq.

The Tasy and the Taigon, both over two feet at the withers, are fast, robust, determined, all-purpose hunting dogs and like the similar breeds of Chortaj (pronounced Hortai) and the Steppe Borzoi, remain unrecognised by most international registries. This means that their breeding remains in the hands of the hunters not the exhibitors. The Tasy hails from the desert plains east of the Caspian Sea, featuring a ringed tail and heavy ear feathering, with a likely common origin with the better known Afghan Hound, sometimes called the Tazi in its native country. Used on hare, fox, marmot, hooved quarry and even wolf, the Tasy is remarkably agile, with a good nose as well as great speed and legendary stamina, often being used with the hawk, providing fur pelts as well as meat. One famous Tasy was valued at 47 horses, such was its prowess in the hunt.

The Taigon operated further east, in the high altitude Tien Shan region on the border with China. Used, sometimes with falcons, to hunt fox, marmot, badger, hare, wildcat, wolf and hooved game, these sighthounds could follow scent too but were renowned for their extraordinary stamina at high altitude. They may disappear as more urban living consumes their fanciers but their blood could be so valuable to the inbred pedigree sighthounds of the west. But of course, breed purity comes ahead of performance in today's canine agenda, despite the health dangers of close inbreeding for over a century.

Further south, the time-honoured Cossack tradition of coursing is conducted on the vast steppes from the north Caucasus, west of the Caspian, up through the Volga and Don River estuaries, where abundant game is available, and the Chortaj and the Steppe Borzoi excel. The mounted hunters use a brace of sighthounds and a falcon instead of a gun, a style taken further west by the Tartars. Neither breed has achieved registration and this has permitted the best hunting dogs to be used as breeding material rather than the prettiest poseur in the ring. These hounds are prized for what they can do, once the only test for any sporting dog. The steppe sighthounds are famed for their ability to sprint over huge distances, for their remarkable eyesight and for being able to show great speed at the end of a lung-bursting long chase. Not surprisingly, they possess supremely tough feet.

These South Russian sighthounds have never known food manufactured just for dogs, have never experienced veterinary care and have always been bred for hunting performance; their survival indicates their anatomical soundness and physical robustness and they represent a unique gene-pool, a source for good both from a sporting and a health point of view. As we increasingly impose our moral vanity on the under-developed world and show increasing disrespect to unsophisticated hunters, whether they are seeking fur clothing or food for their table, merely to survive, we need to take stock. In the show ring the judges’s critiques on Borzois are worrying: "The effortless power on the move seems to have disappeared...", with another mentioning "too much emphasis being placed on copious amounts of coat..." When hounds are bred without regard for their physical soundness and the coat becomes more important than the essential wolfhound anatomy, we are heading for the destruction of such remarkable breeds in the immediate future. The tall breeds need soundness of physique most of all; their ability to lead a fulfilling life is prejudiced when their anatomy itself is a handicap. Breeders and owners who rate the coat above structural soundness reveal at once their disrespect for their own breed.