707 How English is our Pointer

How English is our Pointer?

by David Hancock

“…And as one talks of a greyhound of Britain, the boarhounds and bird-dogs come from Spain”. Those are the words of Gaston Phoebus, the famous Comte de Foix who, at the end of the fourteenth century himself owned over 1,500 sporting dogs. A century and a half later, the great canine authority of his day, Conrad Heresbach was writing: “Spanish dogs, zealous for their masters and of commendable sagacity, are chiefly used for finding partridges and hares. In the quest of bigger game they are not so much approved of, for they for the most part range widely nor do they keep as near as genuine hunting dogs.” A fair conclusion from those words might be that at the time both these authorities were writing the then powerful nation of Spain was producing the best bird-dogs and dominating the European market for them. Their origin – like that of our Greyhound may well be rooted elsewhere.

My preferred dog historian, the under-rated Scot, James Watson, wrote in his masterly The Dog Book of 1906: “When sportsmen got a gun so improved as to admit of shooting flying as a regular and not as occasional practice, which we consider was possible as early as 1680, they thereupon made us of this dog, that had the faculty of locating game and stood still in place of rushing on as the spaniel did to put up game…They gave to this dog a name which indicated what he did – point to where the game was. Had he come from abroad, is it not likely he would have come with his foreign name?” In his Cynographia Britannica of 1800, Sydenham Edwards tells us that “The Spanish Pointer was introduced to this country by a Portugal Merchant, at a very modern period, and was first used by an old reduced Baron, of the name of Bichell, who lived in Norfolk, and could shoot flying…” The Portuguese Pointer is much more like ours than say the heavier Burgos Pointer from Spain.

It is worth a study of the wealthy and well-informed William Arkwright's classic work The Pointer and his Predecessors of 1902 on the question of the origin of our native Pointer. Despite the time and money he clearly spent searching not only Spanish but other continental archives too, he could produce no convincing evidence of a Spanish origin for the breed. But the historical evidence which can be produced demands the most careful scrutiny before definitive statements can be made. I do not believe that the Pointer of Britain originated in Spain or indeed that pointers as a functional type of dog sprang from there, as is usually claimed. It is important though to clarify the nomenclature being used. There are French, German, Italian, Danish, Portuguese, Spanish and British pointers, with several different breeds of pointer within some of those countries. A pointer is a type of short-haired (usually), hound-like bird-dog, rather than one breed. It is misleading and inaccurate, and perhaps overly nationalistic, to dub the Pointer of Britain as the pointer, despite its deserved world-wide reputation.

The Edwardian writer, Rawdon Lee, accepts that the French had their own pointers before the Spanish Pointer was introduced into Britain at the beginning of the 18th century, going on to state that in the latter part of this century: "Pointers far removed from the imported Spanish dog in appearance, were not at all uncommon in England and they could easily have been brought over from France." Sir William Beechey’s portrait of Richard Thompson and Pointer at the end of the 18th century depicts a Pointer very much like the French breed of pointing dog, the Braque Francais. In 1713 Desportes produced his depiction of the Earl of Burlington’s Pointers, with one of them having a distinct continental pointer look to it.

Richardson, writing in 1847, describes seeing Italian Pointers in Scotland, only about a foot high, but remarkably staunch with superb noses. In his The Art of Shooting Flying of 1767, Page remarks: "Pointers. - As nothing has yet been published on these dogs...I am inclined to think that they were originally brought from other countries, though now very common in England." I am inclined to think they were originally brought from other countries too, France, Italy and Spain, with distinctive types from each country of previous development. The modern English Pointer is much more like the French Braque St. Germain than the old Navarro and Burgos Pointers from Spain and the modern Bracco Italiano.

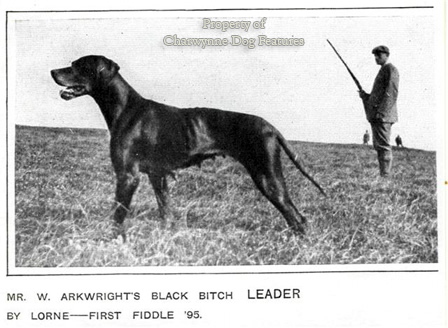

Arkwright's Pointers had considerable influence in the making of today's dog, his all-black Pointer coming from the Greyhound cross and an increasing number of contemporary dogs, both in Europe and America, exhibit the tucked-up loin, the tighter lips and low-set tail from this Greyhound blood. The Pointer of Britain has the eye and the eyesight of a sighthound, certainly no trace of the sunken eye of the scenthound breeds. In temperament too, the Pointer has more in common with the cool, aloof, reserved, rather introverted Greyhound than the gregarious, much more extrovert and certainly noisier Foxhound.

Arkwright himself wrote that: "...the French were the chief admirers of the Italian braque...And after a time, though the heavier type of their own and the Navarrese braque still survived, it was quite eclipsed by the beautiful and racing-like Italian dogs with which Louis XIV and Louis XV filled their kennels." This ability of the domestic dog to indicate unseen game by standing in a frozen posture staring hard at it has been utilised since ancient times. The Greeks identified a breed of dog in Italy, called the Tuscan, which was covered with shaggy hair and would actually point to where the hare lay hidden, perhaps the ancestor of the Spinone. Wolves have been known to display the same capability however and many non-sporting breeds of dog have also demonstrated this instinctive trait.

This scenting skill, supported by the classic pointer stance, has been of great benefit in the shooting field, especially in the days when 'walked up' as opposed to driven game was the favoured style. In the quest for improved scenting powers, the outcross to the Foxhound was made and some experts like William Humphrey, of Wind'em Pointer fame, have claimed to be able to spot Pointers with Foxhound blood in them from their tendency to seek ground scent as opposed to air scent. This is the expected penalty from using tracking dog blood.

Professor J.M.Beazley has traced the origin of our modern English Pointers back to seven discrete families and shown how these original family groups led to the emergence of two main lines of descendants from 1840 to 1980. This may indicate a small gene pool but that doesn't mean the sealing of type forever more. Genes act randomly and type has to be actively sought. For me, our contemporary Pointer is too lightly constructed, too Greyhound-like. The Pointers depicted in paintings from past centuries show dogs with far more substance. It was sad to read the critique of the Pointer judge at Crufts in 2009, which read “The movement on the majority of these dogs and bitches was quite unbelievable, from crossing in front, upright in pasterns, upright in shoulders and it became very soul-destroying watching so many bad unsound movers.” For such a magnificent English gundog breed at our premier dog show to exhibit such serious faults is truly distressing.