676 TERRIERS OF THE NORTH

TERRIERS OF THE NORTH

by David Hancock

“For many centuries the northern counties of England have been famous for the gameness and the working ability of the terriers bred there by hard-bitten breeders who cared not at all for appearance and whose estimation of a dog was based solely upon its prowess in the field. These terriers were known by a number of names, usually associated with the district in which they were bred – a custom which led to almost identical strains being known by different names. This tended to baffle the stranger visiting the north until, within comparatively recent times, clubs were formed and a common name for the breed chosen.”

from The Book of Terriers by CGE Wimhurst, Muller, 1968.

If you look at the annual registrations of some pedigree terrier breeds from the north of England, you could be forgiven for thinking that terriers from that part of Britain are not popular. Each year only around 300 Lakelands, 500 Bedlingtons and 130 Manchesters are newly registered to swell the ranks of those breeds. But away from the show ring breeds from the north, unknown to the general public, yet valued as working terriers, are lesser known less publicised types like the Fell and the Patterdale. Some might claim that the latter are only offshoots of the perennially and deservedly popular Border Terrier, which boasts around 9,000 annual registrations with the Kennel Club. But, despite its lack of separate recognition, the Fell Terrier especially is gaining respect as a working terrier type. The Airedale I do not consider here; it came from a hound background, was never intended to be, and never could be an earth dog and is, in French terms, a hunting griffon. But the old black and tan rough-haired terrier may have contributed to its development and is worth a glance.

At the time the Reverend John Russell was hunting on Exmoor, there were Cheshire Terriers, Shropshire Terriers, Suffolk Terriers, Elterwater and Reedwater Terriers. John Benson had some really hard terriers running with the West Cumberland Otterhounds, as did the renowned Tommy Dobson in the Cumberland lakes, Tom Andrews the Cleveland huntsman, the Earl of Macclesfield in Warwickshire and Squire Danville Poole at Maybury Hall in Shropshire. Some of these are perpetuated in today’s pedigree terrier breeds but behind many of them is the old black and tan rough-haired terrier, never recognised in England as a distinct breed and snapped up by enterprising Welsh terrier fanciers and given their nation’s name.

Today’s Lakeland Terrier represents the old rough-coated black and tan dog, with the undervalued Manchester Terrier representing the smooth variety. If you look at books devoted to terriers of a century ago, you could be forgiven for missing any references to the Lakeland Terrier. Darley Matheson’s Terriers of 1922 doesn’t list it and Pierce O’Conor’s Sporting Terriers a few years later only contains an illustration of “a working terrier from Lakeland” which resembles a Border Terrier. He gives no words on this breed but finds space for two paragraphs on the Otter Terrier, whilst admitting that it was probably extinct. But Hutchinson’s Dog Encyclopaedia of 1934 has 10 full pages on the Lakeland, including 18 photographs. A dozen years earlier, from the names of Patterdale, Fell, the Coloured Terrier and the Elterwater Terriers, the breed title of Lakeland became accepted in the show ring, a breed club having been formed in 1912, with KC recognition being achieved in 1921, a year after the Border Terrier. Less than half a century later, a Lakeland Terrier went Best in Show at Crufts then Best in Show at the prestigious Westminster show in America the following year, some achievement.

The breed title of Bedlington Terrier does scant justice to such a capable all-round hunting dog; if anything the Bedlington is a pedigree lurcher, whose blood is much valued by lurcher men. As a breed, the ancestry of the Bedlington is, relative to most breeds, well-documented and free from myths. From the celebrated hunt terriers, Peacham and Pincher of Edward Donkin of Rothbury to the nailors' terriers in the Northumbrian village of Bedlington itself, from Joseph Ainsley's dog and Christopher Dixon's bitch and their offspring, the prototype Piper and Coate's Phoebe, came the foundation of the breed. Mention is sometimes made of the use of blood from small Otterhounds, Bull Terriers and an infusion of Whippet too, in the development of the breed. But little reference is made to the origin of the distinctive topknot, the highly-individual linty coat and the range of self-colours in the breed.

There was a dog with a topknot and a tight linty-twisty coat in light liver on the Berwick coast and up into the Cheviot Hills at the time the early types of Rothbury Forest Dog were emerging. It was known locally as the Tweed Water Spaniel, but Tweed Water Dog would have been more accurate. Water Spaniels have the marcelled coat texture, as the American Water Spaniel illustrates. Water Dogs have the 'poodle-coat' as the Italian, the Spanish and the Portuguese Water Dogs demonstrate. Water dogs have long been favoured by the gypsy community, with gypsy families like the Jeffersons, the Andersons and the Faas, living in the Rothbury Forest at the start of the 19th century. They were famous for their terriers, long-dogs and water dogs. I believe that the distinctive coat of the Bedlington comes from a water dog origin. Another much-respected terrier breed from the north is the Border.

In his book on working terriers, Dan Russell writes: “I know that I am standing up to be shot at when I say that I believe that the qualities I have detailed are more often found in the Border Terrier than in any other breed. To me, these little northerners are the ideal terriers. They are dead game, they have stamina, nose and endurance, and their little heads seem to be packed full of commonsense. There is in the expression of a Border Terrier an implacable determination which is seen in no other breed.” From that source that is praise indeed. But some claim that the Border, and indeed the Lakeland, is too hard a terrier, just too tenacious, often being unavailable for work because of injuries sustained in needless combat.

In his book on hunt and working terriers, Lucas writes of the Border Terrier: “Many Masters of hounds that they are too hard, or apt to become so, killing their fox instead of bolting him. That this is sometimes the case is not unlikely, for it must be remembered that in the Fell and Border countries it is often necessary to kill foxes by any means possible.” That explanation also explains how the country and its special challenges lead to the need for a responding capability from sporting dogs. Lucas appends in this book a list of the terrier breeds employed by the various hunts at the end of the 1929 season; the Border Terrier is the choice of many. But even as assiduous a researcher as the late Brian Plummer admitted: “As with all northern breeds of working terrier, the origin of the Border Terrier is obscure though there has been much speculation as to how the breed was first developed out of the heterogeneous mish-mash of types that spawned not only the Border, but also the Dandie, the Bedlington and possibly the Lakeland terrier.”

Nowadays we relate to breeds far more than our sporting ancestors; breed purity was never a requirement for a working terrier, performance was all. The types favoured by terrier-men were proven workers, judged not on coat-colour or texture, height at shoulder or shape of skull and often from mixed ancestry. As Richard Clapham wrote in his Foxes, Foxhounds and Fox-Hunting, (Heath Cranton Ltd), of seventy years ago:

“Some of the best all-round working terriers today are to be found with the fell foxhound packs in the Lake District. They are practically all cross-bred, with Bedlington, Border, etc., blood in them…in the land of the dales and the mountains the only criterion of a terrier is working ability, first, last and all the time.”

In similar vein, no claim was made on names for types favoured in different areas. As terrier expert Mossop Nelson wrote in WC Skelton’s Reminiscences of Joe Bowman and the Ullswater Foxhounds, published in 1921 by Atkinson and Pollitt:

“I have a great feeling about keeping to the old breed of what has sometimes been called the Patterdale terrier: brown or blue in colour with a hard wiry coat, a narrow front, a strong jaw, not snipey like the present show fox terrier, but at the same time not too bullet-like to show a suspicion of bulldog cross – a short strong back, and legs which will help him over rough ground and enable him to work his way underground.”

It is noteworthy that the writer was stating what the terrier required to do his job best, rather than what cosmetic points the breeder or owner wished to bestow on it.

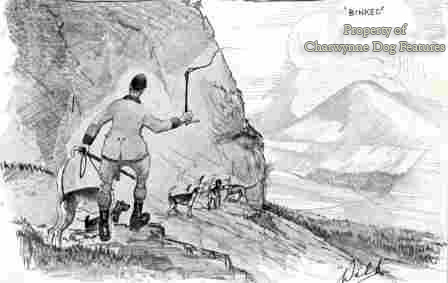

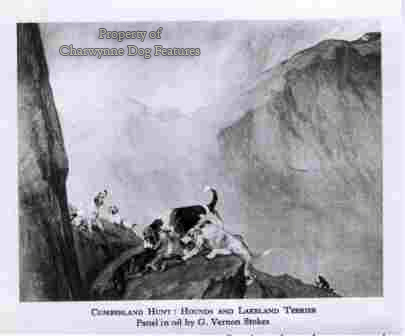

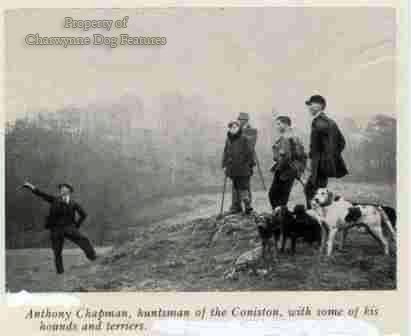

A correspondent to The Field magazine in 1886 wrote: “The dormant spirit of an old fell hunter has recently been keenly awakened at the mention of the Elterwater terriers, which breed, I am informed, is nearly extinct…The Elterwater terriers had plenty of go in them, and no shaking or trembling at your heels, in frost and snow, like so many of the terriers of the present day.” Elterwater is near Rydal, just north of Lake Windermere, Patterdale is some ten miles south of Rydal, at the southern end of Ullswater. Eighty years ago, the Eskdale and Ennerdale Hunt was using six couples of working Fox Terriers, whilst the Coniston Hunt was using the Fell type. The Border Terrier, also called the Reedwater Terrier, the Cheviot Terrier, the Ullswater Terrier (even Joe Bowman’s terrier) and the Robson Terrier (after the Master of the Border Hunt) was favoured by the North Tyne Foxhounds. Always with terriers, their devotees have the firmest of views about the best type for the job in their hunt country. It is of interest that unlike their Scottish counterparts, the terrier-men of Cumberland favoured the drop ear on their dogs, or what they called ‘latch-lug’t’ ears; prick-eared dogs were rarely preferred.

The ban on ear-cropping may well have been the kiss of death to the smooth-coated black and tan Manchester Terrier, for it has never been popular since that time, despite its many virtues. More famous in the rat-pits than as an earth-dog, this handy-sized, easily-managed, companionable little breed is strangely undervalued, both by sportsmen and pet-owners. Accused of lacking ‘gameness’ and handicapped by weak hindquarters and straight stifles, it is making a slight comeback despite its small numbers. In 1909 only 83 were registered with the Kennel Club. One hundred years later that annual figure has risen to 135, still less than half that of the Lakeland Terrier. I attended the annual show for this breed a couple of years ago and, whilst noting great variation in the quality of movement between exhibits, found much to admire in their temperament and companionable qualities. With a trouble-free coat, a total lack of aggression, yet plenty of spirit, they have much to offer as a canine companion.

In his book on the Fell Terrier, Brian Plummer makes a point for me, whilst discussing a visit to terrier-men in the Lake District, on the journey back, with his travelling companions, when one states quietly “They’re a different breed of person”. All of them agreed. The terriers of the north are different breeds too, but each one has its own special appeal. They were developed in the hardest of hard schools and we owe it remarkable breeders such as Joe Bowman, Tommy Coulson, Cyril Breay, Frank Buck, Gary Middleton and Brian Nuttall to perpetuate their years of devoted attention to their outstanding terriers. William Hazlitt, writing in 1821, in his Table Talk, could have been describing terriers from the north, when he wrote: “A rough terrier dog, with the hair bristled and matted together, is picturesque. As we say, there is a decided character in it, a marked determination to an extreme point.” Terriers from the north of England certainly possess and display ‘decided character’ as well as ‘a marked determination to an extreme point’; that’s what makes them the sporting dogs they are.