568 Essential Deerhound

THE ESSENTIAL DEERHOUND

by David Hancock

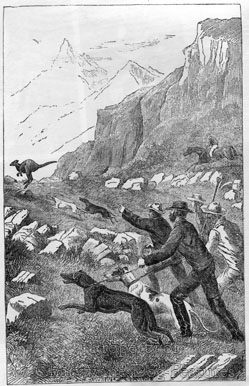

Deer hunting, whether stalking, coursing or tracking, has embraced a number of different breeds and mixes of breeds. Collies and Foxhounds have been utilised, although never in the coursing role. Sir Walter Scott, himself a Deerhound owner, writes of deerhunting involving black St Huberts, but as par force hounds not just scenthounds. But when deerhunters wanted their quarry 'run down', the Deerhound was the choice. Some of the early show specimens only came into the hands of show breeders and exhibitors because they were too tall for deer coursing. Now, the breed standard asks for a minimum desirable height of 30 inches at the withers for dogs. The seeking of great size in dogs has little historical support and no functional advantage. No Greyhound reaching 30 inches at the withers has ever won the Waterloo Cup, once the most competitive match in the sighthound calendar.

Deer hunting, whether stalking, coursing or tracking, has embraced a number of different breeds and mixes of breeds. Collies and Foxhounds have been utilised, although never in the coursing role. Sir Walter Scott, himself a Deerhound owner, writes of deerhunting involving black St Huberts, but as par force hounds not just scenthounds. But when deerhunters wanted their quarry 'run down', the Deerhound was the choice. Some of the early show specimens only came into the hands of show breeders and exhibitors because they were too tall for deer coursing. Now, the breed standard asks for a minimum desirable height of 30 inches at the withers for dogs. The seeking of great size in dogs has little historical support and no functional advantage. No Greyhound reaching 30 inches at the withers has ever won the Waterloo Cup, once the most competitive match in the sighthound calendar.

It is interesting to note the height of past Deerhounds: M'Neill's Buscar (1836), a celebrated purebred worker, was 28 inches at the shoulder; Morse's Spey (1880) was 26 inches at the shoulder; Spencer Lucy's Morna (1879) was 26 inches high; the Duchess of Wellington's Lady Garry (1885) was 26 at shoulder. In his valuable book of 1892 on the breed, E Weston Bell wrote: '...for the work this dog had to do, if we take his general appearance at over 30 inches, he would be almost too heavy and clumsy...' And when considering 'the work this dog had to do', it is worth noting that in 1563, at a tainchell or deer-drive arranged by the Earl of Athol, 360 deer, 5 wolves and some roes were killed in one day, with two thousand Highlanders employed in the drive. It is not easy to imagine hunting on such a scale but likely that several hundred hounds were involved, some of whom would have died. The sheer stamina of the hounds involved that day is simply awesome.

The blood of the Deerhound has long been prized by knowledgeable lurcher men. The noted Deerhound and Deerhound-lurcher breeder, Bill Doherty, has written that 'My pure-bred deerhounds, although never possessing the ability to match the sheer versatility of their cross-bred relations, have also achieved a certain degree of all-round hunting success.' Many sportsmen are most impressed by their hunting skills and quite remarkable facility for detecting movement over huge distances. They can track as well as hunt by sight. Some breeds have lost type in the hands of show breeders but this breed seems to have retained its essential type over several centuries. It is easy to overlook the value of hounds which could hunt red deer successfully before the wide use of long range firearms. In a harsh winter the skill of such a dog could mean the difference between starvation and survival for the primitive hunters. Once this value diminished however, these huge shaggy fast-running hounds fell on hard times, surviving only in some areas through the patronage of the nobility.

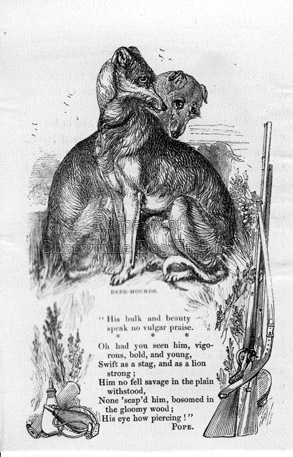

'Idstone' in his The Dog of 1880, writes: 'Many crosses have been adopted...one of the Deerhound and Mastiff has been used by the proprietor of a deer-park in my immediate neighbourhood...I also introduced a fine Morocco Deerhound, which has been used successfully...A remote Bulldog cross has been used also...' He noted that the Mastiff blood produced a hound which went for the ear, the classic hunting mastiff mode of attack, rather than the hock. But the Deerhounds he really favoured, he described as 'They had the racehorse points - the long neck, the clean head, the bright intellectual eye, the long sloping shoulder, the muscular arms, the straight legs, the close, well-knit feet, the wide, muscular, arched back and loin, the deep back-ribs, the large girth, the esprit, the life, the activity which, when controlled and schooled, is essential...' Words worth revisiting by any Deerhound breeder of today.

In his little known book The History of the Dog of 1845, WCL Martin, has written: '...three varieties of the greyhound, if not four, appear to have long existed - viz. the wire-haired greyhound, more or less rough in its coat, as that of Tartary and Eastern Russia; a silky-haired breed, as that of Natolia, Persia, and ancient Egypt; and a smooth-haired breed, now common in England, but which was first introduced into France...' He went on to speculate about the Scoti originating from Scythia in southern Russia and bringing their hounds with them, via Gaul, into Ireland, then on into Argyle, the land of the Gael or Gaul. All the hounds which hunt using their speed have an ancient origin and have retained their phenotype, shaped by function, down the centuries. The first mention of Deerhounds is in Pitcottes's History of Scotland where it states that 'the king (1528 AD) desired all gentlemen that had dogges that war guide to bring them to hunt...the Earls of Huntlie, Argyle and Athole, who brought their deirhoundis with thame...' But Pennant produced the first description of these 'true Highland greyhounds.'

Pennant recorded, when visiting Scotland in 1769, that he saw at Gordon Castle true Highland greyhounds which had become very scarce. He described these hounds as "of large size, strong, deep-chested, and covered with very long and rough hair", used "in large numbers at the magnificent stag chases by the powerful chieftains." Lurcher men, keepers and stalkers refer to them as staghounds to this day. The Earl de Folcoville had his noted Colonsay strain in the first half of the 19th century. MacNeile, in his chapter on Deerhounds, the first detailed write-up of the breed, in Scrope's book on deerstalking of 1838, described one of the purest specimens: "This dog is of pale yellow, and appears to be remarkably pure in his breeding, not only from his shape and colour, but from the strength and wiry elasticity of his hair, which by Highlanders is thought to be a criterion of breeding." MacNeile stated that the grey dogs appeared to be "less lively and did not exhibit such a development of muscle, particularly on the back and loins, and have a tendency to cat hams".

The classic use of Deerhounds involved a brace running down and killing their quarry unaided. This demands not just speed, strength and stamina but superbly constructed dogs, whose limbs and, especially, their feet, can cope with boulder-strewn terrain at great speed, whose joints can withstand fierce jarring and whose physique combines great power with lightness of build. The first point my eye seeks out in a moving Deerhound, even in a show ring, is a noticeable springiness of step and "daisy-clipping" action from the feet; for me all other points are subordinate to this essential feature. It reveals soundness, as well as demonstrating a slingy athletic gait.

This breed is descended from a primitive hunting dog, prized for its field prowess, famed for its strength and speed and essentially a functional animal, not an ornament. In his book on working Deerhounds, Bill Doherty writes: 'Exaggerated show points were bringing in faults at an alarming rate; shortcomings and structural faults that wouldn't get better or disappear with age and that would be found out in the field of work, even if deliberately ignored in the show ring.' Faults which persist can only be ones ignored or overlooked.

I would much rather have an overall sound dog of 28" at the withers than an oversized unsound dog. An inch or two in stature can never match the overall soundness so essential in a hunting dog. Deerhound blood has been utilised not just by lurcher men in Britain but by their opposite numbers hunting coyotes in America and kangaroo in Australia. Such breeders are seeking all round hunting skills: a good nose, coursing ability and the keen determination to pursue a fast quarry over some distance. The use of Deerhound blood is a sincere compliment.

Writing in his "Dogs of Scotland", published in 1891, Thomson Gray remarked that: "Another great drawback in connection with deerhounds is that they become small and weedy through interbreeding...all breeders will acknowledge that it is a serious one". Nobody wants the Deerhound to have the narrow head of the Borzoi or Greyhound but if this pedigree breed does need an infusion of new blood there are some fine Deerhound type lurchers around, although far too many of the latter are rather coarse-headed and often over-boned.

The Deerhound in the United States has the highest percentage of dilated cardiomyopathy seen in breeds there. These dogs come from British stock. Although hip dysplasia is not a common problem in the breed, osteochondritis, and torsion of the stomach, spleen and lung have been recorded. Lurchermen utilising Deerhound blood would be wise to obtain health checks before investing in breeding material. Stature too in this breed should be based on their hunting potential and never on sheer size alone; this is a fine sporting breed ahead of an ego-booster. I agree with Bill Doherty when he writes: 'Gargantuan show specimens with their exaggerated points will rarely, if ever, emulate the soundness, health or working abilities of the various working deerhounds...'

Critiques on Deerhounds in the show ring in 2007 included these faults: too many light eys, large ears and upright fronts, weak pasterns, splayed fronts, weak quarters and a lack of muscle, lack of spring of rib, poorly knuckled feet, poor front assemblies - with elbows in front of chests and untypically wide behind. This is not encouraging. If I were going to buy a Deerhound, I'd get one from the Doxhope kennels of Bill Doherty. A respect for the function of a hound, however distant, is the way to breed a sound animal, more today than any day in the past, as hunting becomes a mere memory.