532 CONSERVING OUR SCENTHOUNDS

CONSERVING OUR SCENTHOUNDS

by David Hancock

“The most careless observer of the course of world affairs must be aware that – as has been the case in all ages – in proportion as a country has arrived at the highest pitch of wealth and refinement, the taste for the humble, but nearly unalloyed pleasures of a country life, has more or less declined.”

“The most careless observer of the course of world affairs must be aware that – as has been the case in all ages – in proportion as a country has arrived at the highest pitch of wealth and refinement, the taste for the humble, but nearly unalloyed pleasures of a country life, has more or less declined.”

Nimrod, writing in his The Life of a Sportsman of 1903.

Unprecedented Challenges

I have long striven to argue for stronger support for the hound breeds and packs. Both face unprecedented challenges in the 21st century. Without a test of function every sporting animal is much more likely to be bred to a mistaken design. In the show ring the exaggerators will strive to defend the harmful work of their predecessors, often arguing that ‘traditional type’ and breed integrity is threatened when overdone physical features that handicap the dog are questioned. But history is not on their side – our more distant sporting ancestors never sought excess in the anatomies of their charges. There is ample evidence, in paintings, sketches and early photographs to demonstrate the imposition of fairly modern exaggerations currently afflicting a number of hound breeds. The show ring is about canine beauty not canine soundness and this has to stop. But before the hunt followers get smug, harm too has been done in the hunting packs, in the past by the absurd desire for ‘great bone’ and in more recent times by ill-informed breeding to hound show winners, not to proven field performers. We all love a handsome hound but an incompetent one is an embarrassment.

Each native breed of scenthound, whether in the packs or on the show bench, has problems to be faced, whether threats to its health and virility or to its existence at all. A century ago this was not the case. Imported hound breeds too have difficulties over their future here and in the form they are being cast in. It is pointless to moan about the loss of our sporting heritage when hound breeds are under threat; what is needed is vision, an ability to look ahead and plan their survival in challenging times. Just as so many of these long-established breeds were shaped by knowledgeable sportsmen and bred for a function by skilful informed breeders, we now need inspired patronage from a new generation, able to live in changing times, adapt to contemporary attitudes, yet manage to conserve country sports albeit in a reshaped form. Hounds are much more adaptable than we imagine; when the ‘quarry’ changes they can change too. The pursuit of scent is their whole life and, as the trail hound fraternity have demonstrated, nose, pace and scenting skill can still be tested in our eager hounds. I admire the work of the Bloodhound community in running their special stakes annually; their Brough, Bracken and Kelperland stakes provide a great test to find working champions amongst the show hounds in their kennels – and what spiritual exercise for both hounds and humans!

Loss of Role

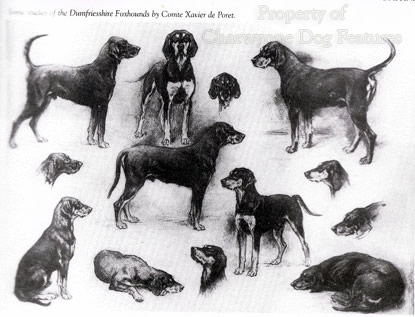

Those involved in the world of hounds used for hunting need support if our precious packs of hounds are to be conserved. We have already lost the distinctive and highly efficient Dumfriesshire pack of black and tan Foxhounds. This alone represents a considerable loss of unique irreplaceable genes from the packhound pool. We need to give thought to the long-term future of our Harriers, Staghounds, English Bassets and that valuable breeding source: the Welsh Hound. With the new emphasis on 'Britishness' perhaps the hunting dogs of Britain will receive some much-needed interest from the public. The public try to care about conservation but have long been badly informed by the popular press about hunting with hounds. The Otterhound has reached the KC rings, one form of conservation. From their long and mixed ancestry, it would be a tragedy if their appearance became increasingly exaggerated, as so often happens with longer coated and longer eared breeds. The show ring Basset Hound indicates all too clearly what can happen to a breed when its distinctive features become distinctively exaggerated; the ear and back length in the show hounds not being fair on the dog. The Bloodhounds of the show ring too display an ear length and head wrinkle not present in their distant ancestors.

Anatomy to Succeed

The standard of mouths, dentition especially, can deteriorate away from the packs; strong teeth, even teeth, and a scissor bite are all important in a hound. Variation in shoulder height is not a bad fault in scent hounds, where packs are bred to suit country, as long as the hound is balanced, free-moving, vigorous in action and not clumsily cumbersome through being too rangy. A fault to be penalised in any scenthound is when depth of rib does not reach back the whole length of the ribcage; lung room is vital. The fate of many foothound breeds now rests with show ring breeders. It is a challenge and a considerable responsibility. Otters no longer pose a threat to our larders and are rightly conserved. So too must be the hounds which once hunted them, they are an important part of our sporting heritage. If we do not respect their sporting past and only breed them for their coats, the 'uniqueness' of their ears, a 'very loose and shambling'gait and 'exceptional' stride, as their breed standard demands, then we will be betraying the work of past breeders like Captain Bell-Irving with his renowned Dumfriesshire Otterhounds. May such hounds whether in minkhound packs or in the show ring go from strength to strength, a distinctive hound well worth saving. But so too are the other packhounds.

The contrast between, say, the Beagles in the Dummer pack and the show ring specimens, as far as type and size is concerned, is stark. I see show ring Beagles that are handsome enough, but barrel-chested, over-boned and straight-shouldered. There is no benefit to a hare-hound in such limitations to pace and stamina. I see Bloodhounds in the show ring that seem to be prized for their excessive facial wrinkle, sunken eyes (giving a strangely-desired ‘sad’ look) and the looseness of their lips. What would a tracking hound, let alone a pack hound, gain from such unnatural features? The pack Bloodhounds resemble their ancient ancestors. For me, the best-bred hounds in the show ring are the less well known Bassets Fauve de Bretagne; the entry I have seen, at the Bath Dog Show in particular, over several years has been quite excellent, yet never been selected for Group or Best-in-Show honours. They appear to have the anatomy to succeed in the hunting field. We have no equivalent native breed but we do have our overlooked hunting Bassets and elegant well-bred Harriers.

Fluctuating Fortunes

A glance at the registrations of hounds with the KC reveals the fluctuating fortunes of most breeds. In 1908, scenthound breed registrations were: Basset Hounds 15; Beagles 4; Bloodhounds 113; Elkhounds 5, with no KC registrations of Otterhounds, Harriers (recognized then) and Foxhounds. No other scenthound breeds were recognized then. A century later (2010), the scene is very different for these breeds: Basset Hounds 1003 (up from 25 in 1950); Beagles 2877 (up from 64 in 1950); Bloodhounds 55 (up from 39 in 1950); Norwegian Elkhounds 33 (down from 300 in 1950); Otterhounds 57 (up from zero in 1950), with no registrations of Harriers (still unrecognized, or Foxhounds, despite being recognized). But in 2010, 1,243 Rhodesian Ridgebacks, after only 56 in 1954, 318 in 1980 and 643 in 1992, were registered; a remarkable increase. Yet in Hamiltonstovares, after 31 in 1999, only 6 were registered in 2010. Bassets Fauve de Bretagne went from 40 a year in the 1990s to 117 in 2010. Into the lists came Bavarian Mountain Hounds with 73 in 2010. It is difficult to make rational conclusions from such fluctuations beyond human whim, combined with our fondness for novelty. The success of the Rhodesian Ridgeback as a breed is well deserved – there is responsible breed stewardship here and impressive hounds in the ring; in a previous chapter I set out its evolution, which, like that of the Dogo Argentino, is, unusually in hound breeds, a matter of recorded history. We are denied the latter breed by the ill-conceived Dangerous Dogs Act, but the African hound has truly and deservedly made its mark here.

Buy British!

But why favour a scenthound from Sweden, like the Hamiltonstovare, when we have superlative and very similar hounds here like the Studbook and West Country Harriers? Why import a Grand Griffon Vendeen when we have the highly rated Welsh Hound available, of comparable type? Why, if you fancy the Basset Hound, not go for the delightful little scent hounds developed as the English or Hunting Basset? What are the advantages of the Grand Bleu de Gascogne over our steadfast and long-proven Staghound? And have those now bringing in the Segugio Italiano ever seen a Trail Hound in Cumbria, they really are something special. They race rather than hunt, they run freely rather than as a pack, but their genes are so valuable. They have Pointer blood in them; their breeders sought performance from superb hounds, not pure-blooded fading stock, losing virility, yet still bred in a closed gene pool for 'old times sake' or salient breed points unconnected with performance. We lost the famed Dumfriesshire Foxhounds and now import the similar-looking Bavarian Mountain Hound, much as I admire the latter, already committed to tracking trials that should ‘keep it honest’.

Preserving Bloodlines

Perhaps the best way of ensuring that there is a future for our distinguished varieties of packhound is a sustained cooperation between MFHs and the breed clubs for the show hounds, rather as Beagles and the Albany Bassets were once run. It would be good to see too, from the show ring fraternity, sustained moral support for the packs, financial support for the Countryside Alliance, allied with indefatigable campaigning for the misguided Hunting Act to be removed from the statute book. Those who breed hounds need an incentive. Those who breed superlative hounds anywhere need motivation. Perhaps, a revival of hunting-hound trials, held in the early days of Foxhunting would be of value. In 1829 for example, 600 riders watched seven couples from local packs in the north Midlands compete against each other in a match. At a subsequent contest in Yorkshire, 18 couples competed, with each hound able to score up to ten points, with marks deducted for babbling, rioting, overshooting the hunted line, etc. We shouldn’t leave it to the French to perpetuate such hunting field fun. Let’s keep the activities going. Let's keep the bloodlines going - and the campaigning. For all scenthound pet owners too, I have a plea: afford them spiritual release, give then nose-work, let them go tracking, provide them with sensory stimulation. These dogs were specifically developed over centuries to exercise their incredible powers of scenting; respect their instinctive needs and see the happier hound you have empowered.

“Hunting has become a freemasonry of countrymen who recognize the lamentable truth that the population of Britain now constitutes two nations. One, through no choice of its own, is town-based and, also through no fault of its own, cannot know the facts of life in the fields and woods and farmsteads which lie beyond the points where the pavements end. Ignorance is generally the breeding ground of disapproval and intolerance.”

Wilson Stephens, writing in The Farmer’s Book of Field Sports, Vista Books, 1961.