438 Owtcharkas

FLOCK GUARDIANS FROM THE STEPPES

by David Hancock

The imposing dogs of the flock guarding or mountain dog breeds from around the world have long found favour in Britain. Impressive breeds from Portugal in the west to Hungary in the east and from Turkey in the south to Germany in the north have found their way here. But the huge and often quite fierce pastoral dogs of Russia have yet to attract favour. Russian breeds like the Borzoi and the Samoyed have long been admired here and are now very much part of our dog show world. But the flock guardians or Owtcharkas from Central Asia, the Caucasus and Southern Russia, now the Ukraine, despite appearing at world dog shows, do not feature here. These three distinct breeds are strapping, assertive and very protective dogs of some stature but not exactly pets in our sense of the word. There were plenty at the Helsinki world dog show; some were very resentful of other dogs, many being muzzled, even in the ring. Several were 32 inches at the withers.

The imposing dogs of the flock guarding or mountain dog breeds from around the world have long found favour in Britain. Impressive breeds from Portugal in the west to Hungary in the east and from Turkey in the south to Germany in the north have found their way here. But the huge and often quite fierce pastoral dogs of Russia have yet to attract favour. Russian breeds like the Borzoi and the Samoyed have long been admired here and are now very much part of our dog show world. But the flock guardians or Owtcharkas from Central Asia, the Caucasus and Southern Russia, now the Ukraine, despite appearing at world dog shows, do not feature here. These three distinct breeds are strapping, assertive and very protective dogs of some stature but not exactly pets in our sense of the word. There were plenty at the Helsinki world dog show; some were very resentful of other dogs, many being muzzled, even in the ring. Several were 32 inches at the withers.

The Caucasian sheepdog is very much like the Karst or Istrian sheepdog, the Sarplaninac or Illyrian sheepdog and similar to the brindle form of the Spanish Mastiff. There are, not surprisingly given the distances involved, different varieties of the Caucasian dog: the massive thickset type from Checheno-Ingush, NE of the Caucasus, the taller lighter type from Azerbaijan in the south-east towards Azarbayjan-e-Sharqi in Iran, the smaller squarer type of Dagestan, east of the Caucasus, and the big rangier Kangalian from the border area between Georgia and Turkey. Some experts claim that the best and most uniform specimens actually come from Georgia. Their restriction to these remote areas has led to these dogs being largely unknown in the West. They are becoming better known in eastern European countries and in America, where they became recognised, as the breed of Caucasian Mountain Dog, by the United Kennel Club in 1995.

If you lined up a Caucasian Owtcharka, a Karst, a Sarplaninac, a Spanish Mastiff, an Estrela Mountain Dog, an Anatolian Shepherd Dog and a St Bernard, in a brindle or wolf-grey coat, you could soon see how function decided form in such breeds, as well as how very similar in type they are. This, despite the immense distance from the Atlantic in the west to the Caspian Sea in the east. If you lined up parti-coloured specimens of the Rafeiro do Alentejo from Portugal, the Pyrenean Mastiff, the Pyrenean Mountain Dog, the Anatolian Shepherd Dog, the St Bernard and the Caucasian Owtcharka, again the similarities would be startling. To do their work as flock guardians, mountain dogs or steppe dogs have to have thick, weatherproof coats, size and substance, great stamina and robustness and a strongly-developed protective instinct.

The Central Asian Owtcharka needs less coat but all the other attributes to do its work. The breed is found from the east of the Urals to areas of Siberia and south into Mongolia. The best examples today tend to be in Turkmenistan, where it has been recognised as 'a national treasure'; they can also be encountered in Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan and Tajikistan. Their coats are shorter, but their skin is thicker than the other owtcharka breeds, and their ears and tails are normally cropped. They remind me of a smooth St Bernard. They resemble too the bigger forms of shepherd's dog once depicted here, when used in times past as a shepherd's mastiff or flock guardian. The Central Asian is is a powerful breed, having been used as a hunting dog on boar and bear because of its bravery and dash. Those with tan markings over their eyebrows have been dubbed the 'four eyed Mongolian Dogs'.

The third owcharka breed is the South Russian, white, off-white or grey, long-haired, over 30 inches at the shoulder and weighing around 75 kgs. They remind me a little of the early depictions of our Old English Sheepdog, as portrayed by Reinagle for example. They are similar to the Hungarian Komondor, without that coat texture, being used, like the latter, on the steppes, only in their case in the Ukraine. This south Russian breed is not one to be trifled with; it is known as 'the white giant' in some areas of its homeland and is often harshly treated. There is an old Russian saying which states that a 'pampered South Russian is a killer'! The military have found uses for them but their export is not encouraged. Despite their reputation for 'hair-trigger aggression', you have to admire a breed which can survive such a hard climate, such fearsome predators and stern handlers, over many centuries. Their aggression may have been the key to their survival.

Perhaps we should admire them from afar, all these Russian breeds would find urban living in western countries intolerable. When I see such highly protective dogs at foreign shows, usually securely muzzled and justifiably so, I ponder the provisions of our foolish Dangerous Dogs Act. We are not free to import breeds like the Fila Brasileiro, the Tosa and the Dogo Argentino. When I see them at overseas shows they behave immaculately, both with people and other dogs. Their owners shake their heads in disbelief when I tell them of our law-makers. Our global reputation for common sense, moderation and an enlightened attitude to animals has been undermined. Foreign breeds renowned for their overt protectiveness, like the owtcharkas, can paradoxically but rightly enter our country freely. I am strongly against breed-specific legislation; the law as it stands protects nobody. Dogs of every breed can be successfully socialized; any individual dog of any breed can transgress if not adequately socialized.

Innate protectiveness in dogs does bring with it intense loyalty, as owners of dogs from the flock guarding breeds will know. I was not surprised to learn of the Caucasian Owtcharka, left behind when deposed leader Aslan Abashidze was recently exiled from Adzharia in western Georgia, being reunited with his owner in Moscow after his excessive pining moved all who witnessed it. Abashidze, for all his faults, has been credited with saving this breed from extinction. He was said to have had around 80 of the breed, subsequently auctioned off by the Georgian dog breeders' federation. The breed is reported to have guarded the Soviet side of the Berlin Wall. Their sheer size and immediate suspicion of strangers has led to their employment as guard dogs within Russia. I believe it is incorrect to describe such a breed as aggressive; the flock guarding breeds are overtly protective, of their owners and his property, a most valuable instinct for shepherds and drovers to utilise.

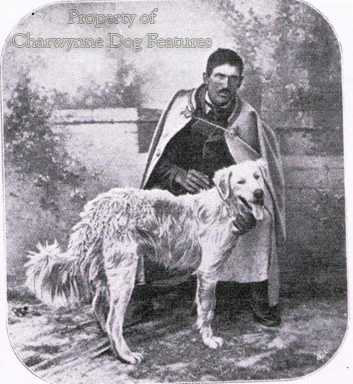

Kohl, in his Journeys in South Russia of 1842, when describing the shepherds there and their dogs, wrote: "The shepherds make their evening meal round a blazing fire, with their twenty watchful dogs encircling them...Between every two shepherds three or four dogs are placed, also at equal distances from each other. In order to make the dogs stay on their respective posts, a piece of an old cloak or sheepskin is laid on the spot...as each knows his own, he is sure to lie down wherever he finds it." Kohl visited Scotland around 1844 and described a drover's dog seen there as a 'wild, shaggy wolf-dog'. Such a dog was oftem described as a shepherd's mastiff.

In his Researches into the History of the British Dog of 1866, George Jesse quotes a Mrs Atkinson as saying of the flock guardian of Tartary she saw near Omsk in West Siberia: "As I looked at her I thought I never saw anything more beautiful; she was a steppe dog; her coat was jet black, ears long and pendant, her tail long and bushy; indeed, it was a princely animal." All over Tartary too, these huge flock guarding breeds were valued. One old saying there stating that: "To ask an Usbek to sell his wife would be no affront, but to ask him to sell his dog, an unpardonable insult". Not a very modern view!

The travels of steppe nomads into Europe and the establishment of the Ottoman Empire ensured that such dogs became known further afield, in the Balkans especially. Ash records a misadventure with an Albanian flock guarding dog in 1859, the writer dubbing it the 'Albanian king of dogs, who is undoubtedly first cousin to the Turkish one.' This account was sparked by a visit to the Islington Dog Show and a sight of Frank Buckland's Turkish Guard Dog being exhibited there. Hamilton Smith writes in 1840 of the dogs used in Persia to guard flocks of sheep, the dog of Natolia, stating they were a deep yellowish red, with a few of them black and white - 'believed to be cross-breeds'. Smith records that a similar dog was found in Central Asia to the Bosphorus.

Fanciers of Anatolian Shepherd Dogs might find that of interest, although the title of their breed still causes controversy. Firstly they are not shepherd dogs in the strict sense, secondly the black-faced ones are called karabash dogs and the white ones, akbash dogs and thirdly, the Kangal Dog is the title favoured by many. In a country the size of Turkey it is likely that local differences would be found in the national flock guarding dog. People in Moslem countries are sometimes alleged to despise dogs but Ash quotes a 1662 account which states that 'There is no people in the world that looks after its dogs and horses as well as the Turk.' Perhaps there is a worldwide difference of attitude between those who use dogs and those who don't.

In the United States, the employment of powerful flock guarding breeds like the steppe dogs has been studied and then applied by Ray and Lorna Coppinger, both biologists. Their subsequent breeding programme has led to around a thousand dogs being placed with farmers and ranchers across 35 states. These dogs, selectively bred to produce ideal flock guarding specimens, come from Italian Maremma, Yugoslavian Sar Planina, Anatolian Shepherd Dog, Hungarian Komondor and Pyrenean Mountain Dog stock, often inter-bred. Brought up from their first days of mobility as pups with sheep, these dogs are now being successfully used to deter predators, much to the gain of sheep farmers. Unlike herding dogs which respond to human commands, these guard dogs have to function without human intervention. These dogs learn not to guard livestock in set locations but to move with the sheep and patrol the area the sheep are grazing in at any one time.

This is the system used by shepherds from the steppes of Hungary and Russia to the highlands of Tibet in the east and of the Iberian peninsula in the west, even taken to Uruguay by the Spanish colonists, leading to the emergence of the Uruguayan sheepdog, so like a Pyrenean Mastiff. Murray, in his Summer in the Pyrenees of 1837, observed that "The Pyrenean shepherd, his dog, and his flock, seem to understand each other's duties. Mutual security and affection are the bonds which unite them." Those few words are an apt summary of the shepherd-sheepdog partnership, which goes way beyond mere dog-ownership. The use of Anatolians to protect goats from cheetahs, baboons, jackals and caracals in Namibia is another present-day example of the value of the timeless employment of big strapping dogs to protect livestock.

The Smithfield sheepdog may have been our nearest equivalent to the fearsome flock guardians of the steppes. There are many depictions of strapping very protre many depictions of powerful very protective larger editions of our surviving collie breeds in paintings of past centuries. But the Tasmanian Smithfields of Graham Rigby in Australia may well represent the last examples of our lost flock guardians. Once predators such as lynx and wolf have been removed, the need for these dogs lapses. But wherever we raise livestock in areas featuring such predators, the protective instincts of these dogs become valued once again.

Big naturally-protective sheepdogs like the owtcharkas of Russia, the Kuvasz breeds of Hungary, Slovakia and Poland and the spaghetti-coated Komondor have long served the shepherds of the steppes and been greatly valued by them. Now, in the New World, their value is being recognised too. It is a rich heritage and one to be treasured. Brave determined protective dogs in any country deserve our patronage. The Leonberger of today may never have carried out this timeless role but for me this impressive breed epitomises both the character and the stature of such admirable selfless dogs - gentle giants of imposing grandeur, forever ready to serve.