391 Whippet

THE WHIPCORD WHIPPET

by David Hancock

Half a century ago, I was working with a group of men from the pit villages of north-east England when the subject of rabbit-dogs came up. One of my colleagues from the south mentioned that his mother showed Whippets and hunted rabbits with them. He was asked how you could put a Whippet in a Kennel Club show when each dog was different. One faction declared that the only true Whippet was the result of a Smooth Fox Terrier crossed with a small Greyhound, back-crossed to a Staffie after five generations. Not one of them would accept that the Whippet was a pure-bred KC-recognised breed with more than ten generations of 'pure' breeding. For them the Whippet had to function; its breeding mattered less than its performance.

Half a century ago, I was working with a group of men from the pit villages of north-east England when the subject of rabbit-dogs came up. One of my colleagues from the south mentioned that his mother showed Whippets and hunted rabbits with them. He was asked how you could put a Whippet in a Kennel Club show when each dog was different. One faction declared that the only true Whippet was the result of a Smooth Fox Terrier crossed with a small Greyhound, back-crossed to a Staffie after five generations. Not one of them would accept that the Whippet was a pure-bred KC-recognised breed with more than ten generations of 'pure' breeding. For them the Whippet had to function; its breeding mattered less than its performance.

Against that background, it is interesting to note that in The Oxford Reference Dictionary (OUP 1986) a Whippet is defined as: a cross-bred dog of greyhound type used for racing. The origin of the word itself is set out as coming from an obsolete word meaning to move briskly. A similar word 'whappet' is defined in the Dictionary of Archaic Words of 1850 as 'a prick-eared cur'. Perhaps my northern friends were on to something! There is a quite expensive book on the Whippet which goes to great lengths to try to prove that the Whippet has existed for centuries, using scores of old paintings and sculptures depicting small Greyhound-like dogs as evidence.

Apart from the fact that it is very unwise to talk of pure breeds before the 19th century, it is ludicrous to claim that small sighthounds have to be Whippets. By that measure the Cirneco dell'Etna of Sicily, the South African native hunting dogs, the Pharoah Hound of the Maltese Islands and the small podencos of the Mediterranean littoral would have to come under that name too. Throughout recorded history there have been accounts and depictions of small smooth-haired sighthounds. In England diminutive Greyhounds were long favoured as ladies' companion dogs, quite separately from the delicate Toy breed of Italian Greyhound.

Some will claim that the Whippet must have terrier blood to be a genuine Whippet, alleging that the Kennel Club show fraternity hijacked this type, made it into a pedigree breed with a closed gene pool, better named Miniature Greyhound than misappropriating the common name given to the rabbit-dog of the mining community of the north-east. It is too late now to undo this recognition but many find it hard to think of a Whippet as a pure breed. Before the days of kennel clubs in the world, pure breeding from a closed gene pool, whatever the quality of the progeny, would have been laughed off the face of the earth, Distinct breed types were prized of course but mainly because of their prowess not their pedigree.

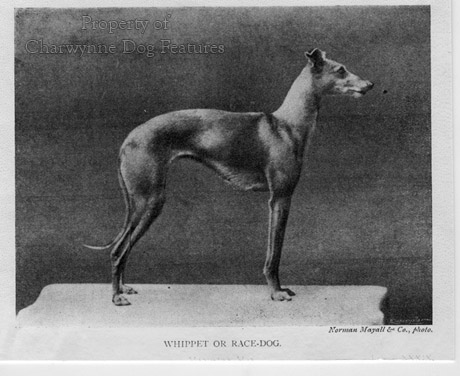

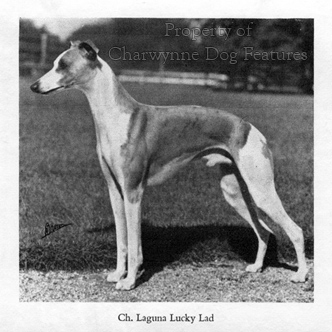

These remarks are not intended as a criticism of show Whippets, many of whom are devastating hunters, or of their breeders, some of whom know a thing or two about breeding sporting dogs. The Laguna Whippets of Mrs DU McKay have a remarkable field and bench reputation. KC-registered Whippets are regularly coursed, with a determined bunch of knowledgeable devotees behind them. They rather shame the show Greyhound fanciers who rarely test their breed in the field. I simply cannot see the point of admiring a hound, designed to catch game using sheer speed if you never wish it to do so. The purpose and the build of such a dog is that of a sprinting machine. A Whippet was once recorded as covering 150 yards in 8.6 seconds; such astounding pace is only achieved if the dog possesses the anatomy which facilitates such remarkable speed.

All sighthounds are 'double-flight' creatures, unlike the horse, a 'single-flight' animal, which for most of its stride, some or all of its hooves are on the ground. The sighthounds race in a series of leaps; they therefore must have extraordinary extension, fore and aft. This is permitted by the slope of the shoulders on the forehand and the pelvic slope in the hindhand. Long legs and a build like a radiator support this degree of extension. The radiator analogy is deliberate; human beings are good at getting rid of excess heat but not good at storing it. Dogs are just the opposite: very good at storing it, not very good at getting rid of it. Dogs give off excess heat rather as a radiator does, they need adequate surface areas to achieve this. If a Whippet when racing or coursing cannot shed excess heat, they suffer; if they reach a temperature of over 108 degrees they could die.

Much is made in conformation shows of 'heart and lung' room in dogs which sprint as their function. The need for lung room I can understand but heart room? The heart stays the same size even during the greatest exertion. What is never mentioned is liver-size. Sprinters run their whole race on sugar mobilized from the liver, liver glycogen. A big liver can store more sugar; sighthounds which run out of liver sugar collapse. It would be worthy research to do post-mortems on the great racing Whippets and Greyhounds and record the weights of their hearts and livers. I would be prepared to bet that these dogs were successful mainly because of their increased heart and liver size. But structure matters too.

After a lack of sheer determination, the biggest fault for me in a sporting Whippet is upright shoulders, so often accompanied by short upper arms. The forward extension determines the forward stride of the dog in the sprint; if you limit that extension you handicap the dog. The shoulder placement is the key to forward movement, well-placed shoulders allow the full forward reach. Any Whippet with a hint of a Hackney-action, that high-stepping prancing front-action of the Toy breed, the Italian Greyhound, should never be bred from. The shoulder blades should almost touch each other at the withers, perhaps one finger's width being usual. I never see ring judges check this feature.

At the back, the falling away at the croup and low-set tail allows full forward reach of the powerhouse hindquarters, the source of running strength. Any lack of slope in the pelvis and the dog has limited forward reach in the rear legs, a terrible fault. Whippets carry their tails low because of this structural need in a running dog. Spitz breeds don't have to sprint for their keep, but have other needs, they display a high tail set and little slope in the croup. Function has long determined form. But just as the saying 'no hoof, no horse' is a perennial truth in that animal, no foot, no dog, is just as valid. I see far too many Whippets with poor feet, weak, not tight and the dog not 'standing up on them', usually a sign of unfitness through a lack of exercise. I have three books on the Whippet which do not have the words foot or feet in their index; they are rather more important than that.

Recent show judges' critiques make a number of points for me: Crufts 2001--"Poor shoulder angulation with short upper arms is still a problem. This was often coupled with heavy shoulders and over-angulated hindquarters resulting in lack of hind power..." Crufts is the showcase for the pure-bred dog; it is depressing to think that dogs with such faults actually qualified for Crufts under Kennel Club-approved judges. An American specialist Whippet judge reported, after judging the breed here: "Straight shoulders were practically endemic...Not nearly enough emphasis is placed on the standard's requirement for 'muscular power and strength' combined with 'elegance and grace of outline'..." This judge also stated finding "exaggerated front action and no drive from behind". For this experienced judge to find straight shoulders practically endemic in a large entry of 212 is worrying. The judge at the N Counties Club show of 2001 reported: "Fronts seem to present the most problems", finding a lack of angulation. A recent Whippet Club show report stated that: "Movement on the whole was not good" complaining once again about upright shoulders, resulting in some 'rather odd front movement'.

I am old enough to remember Whippets in British show rings in the 1960s and 1970s when I recall that firstly the quality was high and secondly show judges' critiques did not mention such disappointing findings. Are we entering an era when show breeders have little concept of what a sporting breed is, an animal designed to function. At this rate we could up with our show Whippets resembling Italian Greyhounds more than their original breed template. If you ally such a concern with the ban on hunting with dogs, then I can only be gloomy about the long-term future of this distinctive little sighthound. The perpetuation of the instinct to hunt at speed and the anatomy which allows the dog to succeed, matter enormously in such a breed. These are essential building blocks not passing whims.

Writing on the breed in Country Life in 1984, I made a number of points for breeders to consider if the breed was to be conserved as a sighthound breed. The only response I had was a rather pompous letter to the Editor from a leading devotee to point out with some glee that I had got someone's name wrong. I really did wonder then if the breed was in safe hands! This is a breed I greatly admire and care about. And before any Whippet fancier shouts so do we, may I ask them to reread the comments made above, not by me, but by experts in the breed. Of course, those who keep Whippets to fill the pot rather than win one, will say 'I know where to get my next working Whippet, why should I care about show dogs?' My reply is "take an interest in the breed as a whole" and I say that to show people too. By that I mean, if you show Whippets, don't lose touch with the working side, the future of the breed as a sporting dog is extremely important.

The Whippet for its size, may well be the swiftest of all animals. Some years back, in a lecture at the Royal Institution on 'The Dimensions of Animals and Their Muscular Dynamics', Professor AV Hill made a number of salient points. He pointed out that a small animal conducts each of its movements quicker than a large one, with muscles having a higher intrinsic speed and being able proportionately to develop more power. The maximum speeds of the racehorse, Greyhound and Whippet are apparently in the ratio 124:110:110 but their weight relationship is in the ratio 6,000:300:100. The larger animal however can maintain its pace for longer periods. Professor Hill suggested that up a steep hill, the speed of a racehorse, Greyhound and Whippet could be in reverse order to that on the flat. It is generally held that a Whippet's best performance is over a furlong on the flat, when it can capitalise on its ability to provide the maximum oxygen supply per unit weight of muscle. This is a very powerful animal.

The breed standard of the Whippet refers to this power in its general appearance section: "Balanced combination of muscular power and strength with elegance and grace of outline. Built for speed and work." I only wish some of the exhibitors at the shows whose critiques I quoted earlier would heed those key phrases. It is pleasing too to see in this breed standard under colour: "Any colour or mixture of colours". This not only gives the breed a rich variety of colours but prevents the absurd colour prejudices which exist in some other breeds. For some pure-breed fanciers the colour is more important than structural soundness. Grattius, writing in the last century BC, gave the view that we should: "Choose the sighthound pied with black and white; he runs more swift than thought or winged light." Oppian subsequently wrote that black and white in combination led to 'overheating'. Edward, second Duke of York, stated in 1406 that: "the best hue is rede fallow, with a black moselle". It is surely the road to failure if any breeder chooses a sire on the basis of colour.

Colour of coat can however mislead judges, due to a trick of the human eyesight. Blacks and blues can appear smaller and more spindly. A dog with a black saddle can appear to have a dippy back. A black patch on the upper arm can give a different impression than a black patch over the withers and down to the brisket. A white underline on an otherwise black dog can make it look shelly. Foreface markings too can create illusions, sometimes shortening the muzzle. Heavy markings on the neck can make it look stuffy when it isn't. Black stockings on a white dog can give a false picture of its gait. Lower leg black markings affect the way the human eye sees leg movement. But if you challenge a judge about such 'trompes d'oeil' the usual response is "Oh, I can't get fooled like that!" I wonder.

But just as coat colours attract much debate so too does coat texture. There was uproar in the American Whippet scene a few years back when a long-haired Whippet, also known as the Wheeler Whippet, was promoted. Critics of these dogs alleging out-crosses need to keep in mind that sighthounds can feature differing coat textures in the same breed, as the Saluki and Ibizan Hound demonstrate. Rough-haired Whippets once featured until the show ring and breeder preferences took charge. But far more important than the colour or texture of the coat is its condition. The skin should be loose, pliable and when pinched up should resume its natural state instantly. A tight dry skin is so often a sign of ill-health.

Size is a long-standing debate in the world of the Whippet. A Durham miner once told me that 60 or 70 years ago, his grandfather favoured an 8lb Whippet, "so's it could fit in y'overcoat pocket". In the breed standard, a male Whippet can be from 18½ to 20 inches high. Such a dog might weigh around 21 lbs. The Whippet Club Racing Association height limit is 21 inches; coursing Whippets must go under the measure at 20 inches. Bigger dogs seem to be favoured in North America. No doubt in time we will see an American Whippet achieve recognition as a 22" specimen, rather as American Bulldogs are bigger than ours or the French variety. I have no problem with sportsmen seeking a hound to suit their terrain but this would be a Miniature Greyhound not a Whippet.

Some years ago, writing in the dog press, Ted Walshe who knows a bit about Whippets, stated: "A coursing dog should be judged on movement first, balance second, and make and shape last; if the first two are right, there shouldn't be much wrong with the third." He also expressed his dismay at some of the dogs presented in the show ring, stating that they 'couldn't catch a cat in a kitchen'. There is rather more to a winning Whippet than a roach back, hyper-angulation in the hindlegs, a straight front and open feet, yet dogs with such features seem to be able to qualify for Crufts; I share Ted Walshe's dismay.

Writing in the Whippet Club's Jubilee Show catalogue in 1950, W Lewis Renwick declared that: "Another important thing to remember is what the breed is bred for. Firstly, he is not a lady's pet dog, despite the fact that no more affectionate breed exists and no dog is happier than when living in the comfort of his master's home. He is first and last a Sporting Dog, his conformation being for great speed over short distances...anybody who has an eye for beauty of form and muscular development must admit there are few dogs so artistic to look upon." These are important words for any Whippet breeder to have in his mind. The Whippet is a canine athlete or it is nothing. As the sporting dog comes under the threat from 'town-thinking' people over its use in the field, we should keep in mind that this breed wasn't evolved for the squires in their shires, but developed by hardworking miners in humble pit-villages. No smart-ass Irish playright could accuse them of being 'the unspeakable in full pursuit of the uneatable'. I pray that Whippets will be catching rabbits, which are very eatable, for many centuries to come.