230 THE RUNNING MASTIFF OF GERMANY

The Hunting Mastiff of Germany

by David Hancock

"The Great Dane was originally designed for hunting the wild boar..."

"The Great Dane was originally designed for hunting the wild boar..."

'Hounds' by Frank Townend Barton, MRCVS, Long, 1913.

“Speed from the greyhound, strength and tenacity from the mastiff, a combination of all three from the alaunt; characteristics necessary to bring a hunt to a rapid and bloody conclusion…hunting par force de chiens, ‘by strengthe of houndes’…

from the Hound and the Hawk by John Cummins, 1988.

Hunting Mastiffs

This web-site covers the mastiff breeds used as holding dogs, the strong-headed, broad-mouthed, modified brachycephalic type, used at the kill in medieval hunting and as capture-dogs since, the world over. These dogs have been used as hunting mastiffs or matins for several thousand years. There are in addition however, what might be called 'running mastiffs', huge par force hounds which hunted using sight and scent, more often on boar. Their surviving examples are breeds like the Great Dane, the Dogo Argentino, the Rhodesian Ridgeback, the Broholmer of Denmark and the more recently developed Catahoula Leopard Dog. These often originated as hounds of the chase, too valuable to be sacrificed at the kill, not trained or bred to be recklessly brave and much more prized for their looks more than any holding dog breed. I have referred earlier to the unjustified false grouping of many of such dogs by modern kennel clubs. On the continent of Europe, the Great Dane is known as the Deutsche Dogge or German Mastiff (literally), but the boarhound/running mastiff ancestry is strangely denied by a number of kennel clubs, including the club of Great Britain, which classifies this breed, not as a hound, but in the Working Group, for show purposes.

Wrong Classification

Theo Marples FZS, editor of 'Our Dogs' in the 1920s, comments on this odd classification in his book 'Show Dogs', stating: "The two breeds (i.e. The Great Dane as a boarhound and the Borzoi as a wolfhound) are exactly on all fours with each other in their sporting use and English relationship, which makes it difficult to understand by what line of logic the Kennel Club has thus differentiated between them on its register." (The Borzoi being in the Hound Group, unlike the Great Dane.) Three quarters of a century later this 'registration logic' is even harder to understand or support. Now accepted by the FCI as a German breed, its emergence as a pedigree breed was in no small way due to English Victorian fanciers of the breed, who formed The Great Dane Club several years before a comparable breed club had been formed in Germany.

Authoritative Writers

But what do the more authoritative writers say on this subject? The esteemed 'Stonehenge' in his 'The Dog' of 1867 writes, on the subject of The Boarhound: "This is the Great Dane, and is used for boar-hunting in Germany and for hunting the elk in Denmark and Norway." Drury, in his 'The Twentieth Century Dog' of 1904 refers to "the great Dane, or boarhound, as it is also called." Dalziel, in his 'British Dogs' of 1881, stated that: "...the Saxons brought with them their Great Danes, and hunted boar with them in English forests and fens." These were the influential writers at the time when our KC was being founded and expanded in its scope; it is difficult to understand why their words were ignored by the KC, even in its infancy. But other knowledgeable writers were ignored too.

Molossian Hound

MB Wynn, in his 'The History of the Mastiff' of 1886, writes that: "...readers and translators should be very guarded how they render molossus as a mastiff, for the true molossian was an erect-eared (altas aure) slate coloured (glauci) or fawn (fulvus) swift footed...dog, identical or almost so, with the modern Suliot boarhound." This is a significant statement coming from such a mastiff devotee. Hamilton-Smith, writing at the end of the last century stated that Great Danes were most likely the true Molossian hound of antiquity. Interestingly, he also states that Caelius and others refer to a race of blue or slate-coloured Molossi (Glauci Molossi). The strangely under-rated Scottish writer, James Watson, in his masterly "The Dog Book" of 1906, writes on the Great Dane: "As to the origin of the dog there is not the slightest doubt whatever that it is the true descendant of the Molossian dog."

Sporting Dog Category

Rawdon Lee included the Great Dane in his 'Modern Dogs, Sporting Division: Vol 1' of 1897, stating: "...that he was used for these purposes (i.e. to hunt the wild boar and chase the deer) long before he came to be a house dog there is no manner of doubt...This is the reason I place him in the Group of Sporting Dogs." The first official record of a Great Dane at the Kennel Club was in the KC stud book of 1878, Marko no.7893, described as an Ulmer Dog. A second Marko, registered in 1879 was actually described as a 'Royal German hunting hound'! No doubts about a hound ancestry there. The distinguished ancestry of the Great Dane is being cast aside by unconcerned and ill-informed kennel clubs and their past sacrifice to man's hunting needs unacknowledged.

Boarhound Function

Hounds that hunted boar were often killed in the hunt and boar hunting in Central Europe down the ages was massively conducted. In 802AD Charlemagne hunted wild boar in the Ardennes, aurochs in the Hercynian Forest and later had his trousers and boots torn to pieces by a bison; all three quarry were formidable adversaries and were hunted by the same huge hounds. The sheer scale of hunting is illustrated by these 'bags': in 1656, 44 stags and 250 wild boar were killed on Dresden Heath; in 1730 in Moritzburg, 221 antlered stags and 614 wild boar were killed and in Bebenhausen in 1812, wild boar were pursued by 350 'strong hounds', clad in armour like knights of old. Hunting big game in Western Europe in the Middle Ages was more an obsession than a pastime - so often a demonstration of manliness.

Scale of Hunting

Between 1611 and 1680, gamebooks reveal that around 40,000 wild boar, sows and young boars were killed in Saxony. In 1737, King Augustus II himself killed more that 400 wild boar in the course of a single hunt in Saxony. John George II, killed over 22,000 wild boar in 24 years. In the Bialowieza Forest in 1890, in a fortnight's hunting, 42 bison, thirty six elk and 138 wild boar were killed. This is the frame in which to picture the Great Dane type as a bison hound, auroch hound, staghound and boarhound. Perhaps because of the wholly arbitrary division of hounds today into scent or sighthounds, multi-purpose hounds which hunted 'at force', using scent and sight to best effect, have been neglected.

Dangerous Activity

It is important too to acknowledge that boar hunting in the ancient world was not just another form of hunting. In his valuable book 'Hounds and Hunting in Ancient Greece', published in 1964 by the University of Chicago, Denison Hull states: "It was the very danger of the boar hunt that made it fascinating to the Greeks; victory was essential, for there was no safety except through conquest. It was that urge to display courage that made the boar hunt the highest manifestation of the chase;" the hounds of course were always in greater danger than the human hunters. Hull quotes from Xenophon's Cynegeticus as recording that boarhounds "must by no means be picked by chance, for they must be prepared to fight the beast". These were clearly highly respected and rather special hounds.

Boarhound Features

In 'Sport in Classic Times', published by Ernest Benn in 1931, AJ Butler notes interestingly that Oppian mentions big-game hounds which are blue-black and considers 'a tawny colour' denotes swiftness and strength. He also refers to boarhounds which have light-coloured bodies with patches of black, dark red or blue. In his 'Hunting in the Ancient World', published by the University of California Press in 1985, JK Anderson writes that the Greek writer Xenophon considered that boarhounds should be "of exceptional quality, so that they may be ready to fight the beast". He quotes Arrian as reporting: "The best bred hounds have a proud air and seem haughty, and tread lightly, quickly, and delicately, and turn their sides and stretch their necks upward like horses when they are showing off." That sounds very Great Dane-like to me!

Irrational Title

I can find no reason for the Great Dane to be so named. The French naturalist Buffon (1707-1788), responsible for so many canine misnomers, called it 'le grand Danois' but, knowing his fallibility, he could have been mishearing the words 'Daim' (buck) or 'Daine' (doe), French for fallow deer, 'daino' in Italian, when packhounds used to hunt deer were referred to by sportsmen. Other references to a Danish dog could have been directed at the Danischer Dogge or Broholmer, the mastiff of Broholm Castle, a Great Dane-like if smaller breed (see below), now being resurrected by worthy Danish enthusiasts. In his authoritative 'Encyclopaedia of Rural Sports', published in 1870, Delabere Blaine records: "The boarhound in its original state is rarely met with, except in some of the northern parts of Europe, particularly in Germany...these boarhounds were propagated with much regard to the purity of their descent..."

Saxon Hound

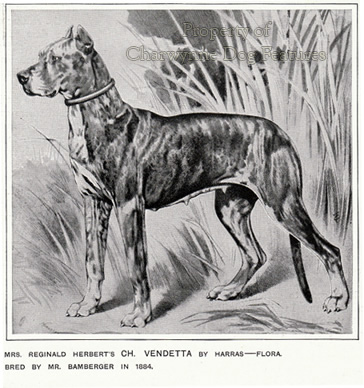

The Great Dane, as a breed type, is believed by some to have been originally brought here by the Saxons, quoting the words "He who alone there was deemed best of all, The war dog of the Danefolk, well worthy of men", in Hel-Ride of Brynhild. The breed was certainly known here in the late 18th century as the well known paintings at Tatton Hall in Cheshire indicate. Two of the breed were presented to HRH The Duchess of York in 1807, being described as Wild-Boar Hounds or Tiger-Dogs from Hesse-Cassel. It is important to note that in the early days of dog shows, e.g. the Birmingham Show of 1884, the breed was actually listed as the boarhound. Wynn in his "History of the Mastiff" of 1886 always refers to boarhounds rather than Great Danes. In 1780 the German artist Riedel portrayed the breed and described it as a Grosse Danischer Jagd Hund, or great Danish hunting dog.

National Dog

In what is now Germany, names such as Ulmer dog, Deutsche Dogge, boarhound or Great Dane eventually became standardised into one breed name: Deutsche Dogge or German Mastiff. It has been argued however that this decision was born out of the need of a reunified Germany to have a national dog, after the war of 1870, rather than any pursuit of historical accuracy. Heavy 'par force' hunting mastiffs imported into Central Europe from England were similarly known as Englische Doggen, translated from the German as English Mastiffs. It is important to note however that artists such as Tempesta, Snyders, Hondius, Hackert and Ridinger produced paintings, etchings or drawings of boar hunts featuring not just prized highly-bred hounds of the chase but also the 'catch-dogs': huge, savage, expendable, broader-mouthed, rough-haired cross-breeds. These dogs, which the French called 'matins', went in at the kill so that the valued hounds of the chase were spared injury from deadly tusks. After all who wants their favoured carefully-bred hound of the chase portrayed and then confused with more casually-bred 'catch-dogs'? . Professor Gmelin, updating Linnaeus in 1792, referred to these catch-dogs as 'boar-lurchers' (canis laniarius fuillus), drawing attention to their strongly made heads.

Molossian Hound

Sadly too, once, later on, as discussed earlier, kennel clubs around Europe wrongly accepted the Molossian dog as a broad-mouthed or mastiff-type dog, the genuine possessors of the Molossian dog phenotype: modern breeds like the Great Dane, the Dogo Argentino and the Broholmer, were lost to hound groups. But, as explained earlier, the word 'Dogge' in medieval Europe meant a hunting mastiff not a catch or capture dog like the broad-mouthed breeds. Hartig, in his 'Lexicon for Hunters and Friends of the Hunt', published in Berlin in 1836, wrote that "The stature of the English Dogge is beautiful, long and gracefully muscular. The stature of the Bullenbeisser is less pleasing." In referring to the 'English Dogge' Hartig meant the hunting mastiff from England. The Bullenbeisser was a catch-dog, the ancestor of the Boxer. Even then, the essential difference between running dog and seizing dog was appreciated. This is not a matter of mere semantics but has fundamental significance in the design of modern breeds for function. When you misunderstand their past function, you get the breed design not just wrong but damagingly so.

Alaunt Link

It is worth noting that the Italian name for the Great Dane is Alano. The alauntes (resembling a mastiff-sighthound cross) were the fierce dogs of the Alans or Alani, who invaded Gaul in the fourth century AD, with settlements on the Rhine and the Elbe. Place names of Alanic origin are Kotzen near Brandenburg, Kotschen near Merseburg, Kothen near Bernberg and Choten-Koppeldorf near Sonnenberg. One variety of the Alaunts depicted and described in Gaston Phoebus's great work "The Book of Hunting" in the early 15th century is very much of Great Dane type. So too are the hounds portrayed by Antonius Tempesta of Florence in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. It must be kept in mind that alaunts were not a breed; Phoebus describes three principal types: one resembling a strong-headed Greyhound, another a powerful hunting mastiff of Great Dane construction and a third a short-faced butcher's dog or catch-dog, the ancestor of the baiting dogs.

German Mastiff

In his celebrated work 'The Illustrated Book of the Dog' of 1879-81, Vero Shaw refers to the Great Dane as the German Mastiff. He mentions a letter from a Herr Gustav Lang of Stuttgart, an authority on the breed at that time, which stated: "The name 'Boarhound' is not known in Germany. In boar hunting every possible large ferocious 'mongrel' was used." If you extend this logic, you should no longer call a Harrier by that name because Beagles and Basset Hounds also hunt hares. Do you stop calling an Elkhound an Elkhound because other breeds also hunt them? I think not. Lang, perhaps unfamiliar with the boar hunt and its niceties, was failing to discern the different functions, at the kill, of running dogs and seizing dogs, the latter considered expendable, the former less so. Specialisation in the hunt too was unusual, big hounds hunted boar, elk and wild bull without being identified as such.

Boar Hunt Used Undedicated Hounds

Herr Lang was however making two points which I do not dispute: firstly that there was no breed of boarhound in Germany, the bigger quarry was hunted separately using the same hounds; and secondly, the boar-hunt utilised large fierce 'killing dogs' of mixed breeds, as well as hounds of the chase. No nation in the world has a breed with boarhound in its title. This is because large hounds did not specialise as a rule. The same hounds hunted stag, boar and sometimes bear and wolf too. In this way, the French used breeds like the Poitevin, the Billy, the Grand Griffon Vendeen and the Grand Bleu de Gascogne for 'la grande venerie' generally. Our own huge scenthounds ended up being called Staghounds, but it was a description of function rather than a breed title; before the loss of wild boar to Britain such hounds would have been used in the boar-hunt too.

Boarhound Link

Herr Lang never disputed that the breed called both the Great Dane and the Deutsche Dogge had once been used as a boarhound, he was disputing the title not the function. Hounds and dogs used in boar-hunts in what is now Germany were called Saurude or Hetzrude, if they hunted in packs, and Saupacker or Saufanger if they were the less carefully-bred catch-dogs. The Americans use huge Bulldogs as catch-dogs with wild hog to this day. In the 1930s an English sportsman in France used a pack of Dogues de Bordeaux to hunt boar. They were boarhounds by function at that time but were mercifully not renamed. It is indisputable that most hounds of the chase used at boar-hunts across Central Europe for a thousand years had the conformation of the Great Dane.

Versatile Hound

In 'Great Danes - Past and Present', Dr. Morell MacKenzie was concerned that "if the Great Dane is considered a hound he is the only representative (although he responds to 'pack law') which does not carry his tail erect or like a flag when on the track." This reveals the ignorance of the writer; such hounds were not purely scenthounds, they were 'par force' hounds which hunted by scent and sight. Why should such a versatile hound carry its stern like a scenthound when it is a more complete hound than that? The Great Dane, as a boarhound, had to have speed and the construction which produces it. The breed needs the pelvic angulation which permits a good forward reach of the hindlegs, more like the sighthounds than the scenthounds. Such a desired pelvic angulation decides set of and carriage of tail in the breed.

Value of Hound Recognition

Once the hound origin evidence is accepted, the pressure for this breed to be transferred to the Hound Group will be irrefutable. Just as the Airedale is King of the Terriers, so too will the Great Dane (German Hunting Mastiff) be King of the Hounds. It will no longer be exhibited on the same day as the sled dogs, herding dogs, flock guardians, heelers, water-dogs and broad-mouthed gripping or holding dogs and be judged by those who know such breeds best - and possibly favour them. It might even lead to a concentration on anatomical soundness and functional athleticism in the breed rather than the mere production of statuesque canine ornaments unable to move with power and purpose.

Deserved Title

The very expression 'Working Breed' undermines and demeans the noble associations and rich sporting heritage of these outstanding dogs. It is time to heed the views of Marples, 'Stonehenge', Drury, Dalziel, Hamilton-Smith, Rawdon Lee, Leighton, Wynn and Watson - can all these distinguished writers really be wrong? Surely Great Dane fanciers should listen to their combined wisdom and then strive, in their own lifetime, to improve the stature of their beloved breed. Breed titles do matter; breeds no longer bred for an historic function soon deteriorate. In his 'Dogs and all about them', published in 1914, the well-respected writer Robert Leighton, stated: "The Kennel Club has classed the Great Dane amongst the Non-Sporting dogs, probably because with us he cannot find a quarry worthy of his mettle; but for all that, he has the instincts and qualifications of a sporting dog..."

Today's Breed

If you accept that the Great Dane is a hound breed, you are able to judge it as one. In studying the breed from the ringside over half a century, I can see the flaws that have been allowed to creep in because it is not being regarded as a hound breed. When you breed intentionally for great size, you risk losing soundness, balance, symmetry and power from the anatomy of that breed. When you only breed for a vague 'Working Group' function, you lose focus and end up with all-purpose canine giants. As a direct result of this, I have seen over many years, often in despair, a potentially superb example of a heavy hound being bred as a huge, gormless, clumsy-footed, all too often grown-up puppy with no idea of what it is meant for. I have seen stunning specimens of the breed abroad, mainly in Scandinavia and Germany, but only rarely in Britain. At the 124th Amsterdam Winner Show in 2013, the Great Dane Diamante della Baia Azzurra was a stunning Best-in-Show, beautifully-proportioned, with impressive movement. The comments by British dog show judges on the breed in recent years are illuminating. The Crufts judge in 2013 reported: "Overall, I am still rather disappointed with the depth of quality in the breed - so many different types, and nothing has improved since I last judged., in fact, probably getting worse. Males worried me the most as here lies our future stud dogs but many are either too feminine in type or too overdone with lots of loose skin, broad back skulls and short forefaces...I do fear for the future of this lovely breed."

General Disappointment

These remarks make depressing reading if, as I do, you care about this fine breed. In 2011, judges at Championship Shows also made worrying comments, as these four quite separate reports from different shows illustrate: "...I was disappointed with the overall quality. Far too many types. Movement was a problem..." "...unfortunately while many Danes have the correct lay of shoulder, they fall short in the length of upper arm or they are loaded on the shoulders and many are pigeon-chested, which of course, affects movement..." "I found several bad mouths; many with not so good front movement." "...I had a lot that had little or no muscle toning and consequently could not move or drive from the rear..." Even more worrying is the fact that judges of this breed have been making comparable criticisms for some years. The Crufts judge in 2009 reported: "...I was less than happy in the quality of many of the Danes present...some of the Danes are too long in the body and in many the front end appears not to belong to the back end. Movement is still on the whole not very good and conformation appears to be going out of the window." At the East of England Great Dane Club's 2013 show, the judge commented: "I do worry about our lovely breed, the quality of the males since I last judged has dropped dramatically..." At the Great Dane Club of Wales's 2013 show, the judge reported: "I wish I could say that the breed is outstanding at the moment, but...there is a lack of overall quality and breed type is very varied." Clearly there is an enormous amount of work to be done by the breeders of this imposing breed - work that could be made easier if they attempted to breed hounds!

Rightful Sporting Place

In the quaintly titled 'Dogs: their whims, instincts and peculiarities' of 1883, edited by Henry Webb, these words are used to describe the German Boarhound: "This giant amongst dogs is placed by strength, activity and courage, in the front rank of his race; as guardian or protector he has no superior, and but few equals. If you look at him when he stands, with all his qualities fully aroused, involuntarily the thought strikes you, I should wish that dog by my side in the moment of danger, well sure I should find in him a staunch friend and mighty champion." Over one hundred years later, we continue to deny such a breed its rightful sporting place in dogdom and are surely lesser people in so doing. We owe this distinguished breed its rightful recognition as King of the Hounds without any further delay.

"...out of a pack of fifty hounds that start on a boar chase often scarce a dozen return to the kennel whole and sound."

Jacques du Fouilloux, 16th century.