186 Our Unique Retrievers

BRITAIN'S UNIQUE RETRIEVERS -- AND THE ONE THAT GOT AWAY!

by David Hancock

Despite the breed name of the Labrador and Chesapeake Bay Retrievers, it is fair, I believe to state that retrievers are very much a British creation. We developed the style of shooting which called for their use and developed the breeds which carry the retriever tag. The all-round excellence of the retrievers has led to their wide use away from the shooting field as guide-dogs for the blind, police tracking and "sniffer" dogs and armed forces' counter-mine dogs. Their response to training, willingness to work, temperament and size make them well suited to the many and varied calls which man makes on dog. The popularity with the dog-owning public of the Labrador and Golden Retrievers continues, with another 50,000 a year being registered with the Kennel Club in the 1990s.

Despite the breed name of the Labrador and Chesapeake Bay Retrievers, it is fair, I believe to state that retrievers are very much a British creation. We developed the style of shooting which called for their use and developed the breeds which carry the retriever tag. The all-round excellence of the retrievers has led to their wide use away from the shooting field as guide-dogs for the blind, police tracking and "sniffer" dogs and armed forces' counter-mine dogs. Their response to training, willingness to work, temperament and size make them well suited to the many and varied calls which man makes on dog. The popularity with the dog-owning public of the Labrador and Golden Retrievers continues, with another 50,000 a year being registered with the Kennel Club in the 1990s.

But when assisting Sally Ancrum, the field-trial judge, to judge a working test at the annual Gamekeepers' Fair some years ago, I was reminded once again of how different our retrievers are, one from another. We tend to overlook, when thinking of retrievers, that different breeds are behind each of them and that they each have quite different breed characteristics. Their function may be the same but the wise owner or trainer would benefit from reminding himself, as I was able to, of their essential differences, breed for breed, and from acknowledging how sensible it is to have this in mind when training a young dog as a retriever.

On this occasion, the most handsome breed was the Golden Retriever; the dogs running being red-gold, the real colour of the breed. How refreshing to see genuine working dogs in this lovely breed: keen but biddable, not too heavy-coated or over-furnished on the legs and tail and full of dash and drive. Red-coated hunting dogs were prized by the ancient Greeks and Egyptians; red-coated Bloodhounds were often found to have the best scenting powers. I suspect too that our own "ginger 'coy dog" (or red decoy dog) of the middle ages, probably now perpetuated in the Nova Scotia Duck-tolling Retriever, has contributed to our contemporary breed of Golden Retriever. This red-gold colouration in dogs has long had genetic significance.

The Chesapeake Bay Retrievers, noticeably less showy than the other three breeds entered, looked so strapping in build and had such impressive waterproof coats. Coming out of the river Trent on the water retrieve test, it was, with this breed just one quick shake and the coat was dry. I noticed too that after handing over the dummy to their handlers, they didn't seek a great show of gratitude or affection---doing the job was for them enough in itself.

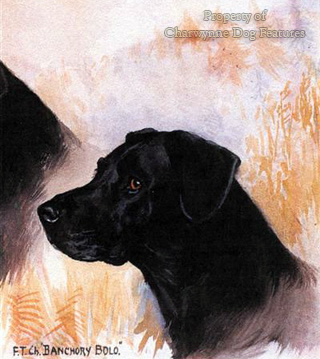

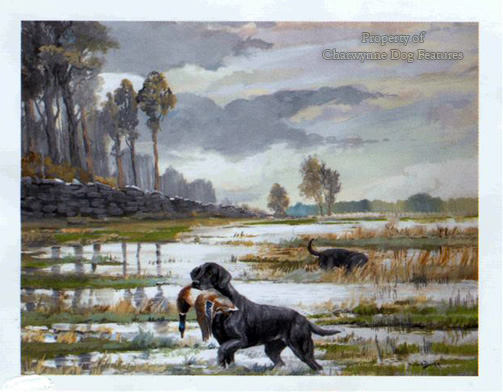

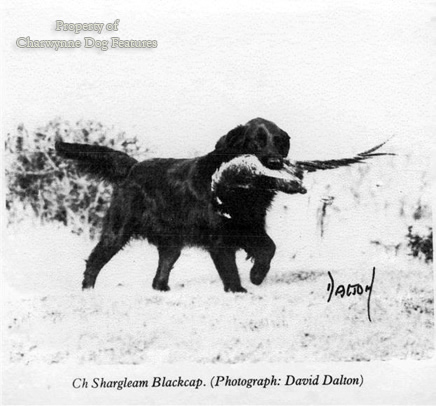

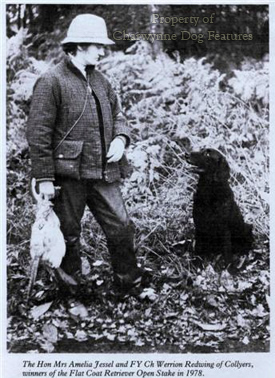

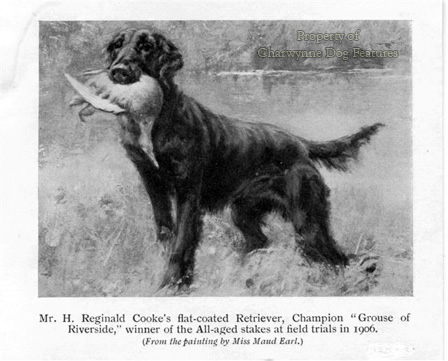

The Flat-coated Retrievers were on this day the best obstacle-crossers, with one of them the best diver I have ever seen. This dog raced to the river bank and just took off, entering the water a good ten feet from the steep bank. I had never really thought of Flat-coats as great water-dogs but this team was fearless, keen, strong in the water and powerful enough to get out with ease. But one moment, on the hidden retrieve in a little copse, revealed the mixed origin of this breed. One of the Flat-coat team was about to go past a half-concealed dummy at speed when his nose told him to stop. As he hesitated, nose higher than the other breeds, his tail went out, a front leg came up and there, for that precious moment, he was the epitome of a black setter. This was for that brief period of time a setting dog at work.

The Labrador team won, their dogs smaller and lighter than the show specimens; their pace, commitment, skill and response to their handlers better on the day. But it needed a "play-off" in the arena to decide the day, the Goldens tying up to that point and heartening all the many admirers of this attractive breed. But it was again on the hidden retrieve that a yellow Labrador's style of game-finding started me thinking of where I had seen that method before. Then the use of the nose, the set of the tail, the gait and the angle of the neck and head reminded me. It was working the little copse exactly as a Foxhound would. Scenthounds use air and ground scent too and the likeness was quite striking. Perhaps understandably the head of this yellow Labrador was "all Foxhound".

Enjoying these differences, it occurred to me how satisfying it would have been to have had the other retriever breeds there too: the Curly-coated Retriever, the Irish Water Spaniel and the Standard Poodle. And before gundog sages start shaking their heads over mention of the latter breed, let me say that one of the best water retrieves I ever saw was by a Standard Poodle, clipped to look like a Curly-coated Retriever and not surprisingly, actually being confused for one.

How fortunate we are to have these valuable breeds of retriever still with us. How important it is to remember their differences and not expect them all to perform like Labradors. For although function will always be of supreme importance, style, individuality and breed idiosyncrasies matter too. I once had two working sheepdogs, one a natural retriever and the other a gifted gamefinder. But for all their cleverness, they could never match the sheer style of the retriever breeds at that working test. Part of the joy of seeing dogs working comes the enjoyment of not just their usefulness, eagerness or skill but their style.

When I see overweight Rottweiler-headed Labradors or over-furnished, biscuit-coloured, so-called Golden Retrievers at dog shows, usually devoid of motivation and demonstrably bored, I sigh for them. Such specimens are not true to their breed heritage in conformation and all too often do not know what they are for. The retrievers at the working test were in a different world: of stimulation, arousing smells, activity, eager excitementand fulfilment. These breeds, valued as much outside Britain as in, were developed in the most testing circumstances: freezing mud, icy estuaries, frozen windswept kale-fields and along ice-cold riverbanks. From such conditions came one breed in particular -- and one which seems to have 'got away', that is, never been registered as a distinct breed.

In his book 'British Dogs' of 1888, Hugh Dalziel, kennel editor of 'The Country' magazine, exhibitor and judge, produced a chapter on the Norfolk Retriever. He largely relied on the knowledge of 'Saxon', a Norfolk sportsman, who provided the text. Dalziel acknowledged that "although Retrievers answering this description may be more plentiful in Norfolk than elsewhere, they are met with often enough in all parts of the country." 'Saxon' describes the coat colour of this retriever as: "...more often brown than black, and the shade of brown rather light than dark -- a sort of sandy brown, in fact." He goes on to describe the coat as looking 'rusty', inclined to be coarse, feeling harsh to the touch, curly but not as close and crisp as in the Curly-coated Retriever of the show ring, tending to be open and woolly. He describes a saddle of straight short hair across the back. Gamekeepers usually docked their tails which made them appear to some sporting writers as spaniels, despite their stature.

These dogs were the wildfowlers' retrievers, used "on broad, river, sea-coast and estuary". It was alleged that the Pointer was not hard enough for such work, the water spaniel too impetuous but the Norfolk Retriever "will face a rough sea well, and they are strong swimmers, persevering, and not easily daunted in their search for a dead or wounded fowl." 'Saxon' claims that Norfolk was outside 'the magic circle of shows' and so the 'improvement' of them has not taken place. He makes it quite clear that this Norfolk dog is different from a spaniel (and appreciably larger) and from the Curly-coated, Flat-coated and Labrador Retrievers.

If you tried to find the contemporary retriever breed to fit closest to the description of the Norfolk Retriever, then the Chesapeake Bay Retriever would be my choice. The breed standard of the latter describes the coat as "harsh...hairs having a tendency to wave on neck, shoulders, back and loins...straw/bracken coloured, red-gold (sedge) or any shade of brown...White spots on chest, toes and belly permissible. The smaller the spot the better." The Norfolk Retriever featured white in the form of a spot on the chest. 'Saxon' stated that the most distinctive features of the Norfolk Retriever was its unique coat and its quite remarkable hardiness. The first sentence of the Chesapeake's standard mentions its distinctive coat and lists one of its characteristics as courageous with a great love of water.

Some authorities have claimed that the Chesapeake Bay Retriever was developed from ship-wrecked Newfoundlands and others from 'Red Winchester' water-dogs out of Ireland. The American writer, Bede Maxwell, in her forthright 'The Truth about Sporting Dogs' of 1972, thought this link might be with a fisheries patrol vessel HMS Winchester which sailed out of Cork to the eastern American seaboard, with officers taking their Irish Water Spaniels with them. This to me is pretty flimsy evidence. Newfoundlands and Irish Water Spaniels have easily spotted anatomical differences from Chesapeakes. And, just as I suspect that the Nova Scotia Duck-tolling Retriever was taken to Canada as the red decoy dog of England, especially from the East Anglia part of England, so too could the Norfolk Retriever. Perhaps some breed researcher could look at the records in Norfolk, Virginia, at the entrance to Chesapeake Bay itself.

If my theory is correct then the great sporting county of Norfolk has missed out in several ways concerning the titles of sporting gundogs. For just as the Norfolk Retriever could be behind the Chesapeake Bay Retriever and renamed in its new country, so too could the English Springer Spaniel have been named the Norfolk Spaniel and the Nova Scotia Duck-tolling Retriever called the Red Norfolk Decoy Dog. In Britain, we respected the backgrounds of both the Newfoundland, which could so easily have become the Landseer Retriever, and the Labrador, which could so easily have become the Malmsbury Retriever, from its early development in England. We lost our Tweed Water Spaniel and English Water Spaniel; the Americans have their Boykin Spaniel and American Water Spaniel. Could we not have our Norfolk Retriever restored to us?

In his valuable book 'The Illustrated Book of the Dog' of 1880, Vero Shaw felt obliged to mention the Norfolk Retriever and wrote that: "It is claimed for this breed...that it is peculiarly adapted for the pursuit of wild birds in the low-lying districts of Norfolk, and that few, if any other varieties of dog, could be found to endure the hard work equally well." In his 'Breaking and Training Dogs' of 1910, 'Pathfinder' wrote of retrievers: "...I have known livers in Norfolk dignified with that prefix, just as it was usual at one time to speak of the English Springer when met there as the Norfolk Spaniel." In his 'The Sporting Dog', published in New York in 1904, the American writer, Joseph A Graham, stated that: "The Chesapeake is not so peculiar or distinct. In fact, he is of rather common appearance. Stout and strong, sedge or rusty brown in color, the coat dense and close, he is not a beauty."

So we have a rusty-coloured, broken-coated, retriever-sized dog in Norfolk, England and subsequently an identical dog near Norfolk, Virginia, at the mouth of Chesapeake Bay. The dog in England is not recognised as a breed, Vero Shaw hinting that it was too nondescript for that to happen. Joseph Graham describes the dog in America as 'of rather common appearance' but it becomes recognised as a breed nevertheless. In his 'The Dog' of 1880, the respected 'Idstone' wrote "Liver and sandy Retrievers have a few partisans. They are the sort which 'always were kept', people tell you, 'in our family'...I know of no family priding itself on this coloured species just now, but I have heard that they are not uncommon in Norfolk." How worthwhile a venture it would be to find rusty-coloured, broken-coated retrievers 'not uncommon in Norfolk', however nondescript, once again and this time recognised as a Norfolk breed.