112 PRESERVING THE HOUNDS OF THE PACK

PRESERVING THE HOUNDS OF THE PACK

by David Hancock

Those involved in the world of hounds used for hunting need support if these precious packs are to be conserved. We have already lost the distinctive and highly efficient Dumfriesshire pack of black and tan foxhounds. This alone represents a considerable loss of unique irreplaceable genes from the packhound pool. We need to give thought to the long-term future of our harriers, staghounds, English Bassets and that valuable breeding source: the Welsh Hound. No doubt the ever active Welsh Assembly has the latter firmly in its sights but not with conservation in mind. With the new emphasis on 'Britishness' perhaps the hunting dogs of Britain will receive some much-needed interest from the public. The public try to care about conservation but have long been badly informed by the popular press about hunting with hounds. The Otterhound alone has reached the Kennel Club rings, one form of conservation. It is worth a look at how this former packhound is faring there.

Those involved in the world of hounds used for hunting need support if these precious packs are to be conserved. We have already lost the distinctive and highly efficient Dumfriesshire pack of black and tan foxhounds. This alone represents a considerable loss of unique irreplaceable genes from the packhound pool. We need to give thought to the long-term future of our harriers, staghounds, English Bassets and that valuable breeding source: the Welsh Hound. No doubt the ever active Welsh Assembly has the latter firmly in its sights but not with conservation in mind. With the new emphasis on 'Britishness' perhaps the hunting dogs of Britain will receive some much-needed interest from the public. The public try to care about conservation but have long been badly informed by the popular press about hunting with hounds. The Otterhound alone has reached the Kennel Club rings, one form of conservation. It is worth a look at how this former packhound is faring there.

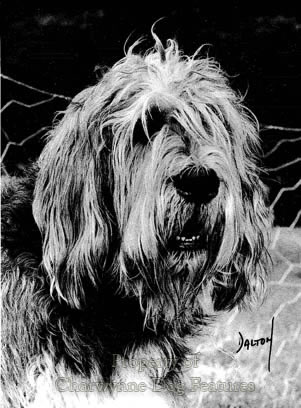

Amiable and boisterous, with the inquisitiveness of a Basset Hound, the perseverance of a Bloodhound, yet without the obstinacy of either, the Otterhound is becoming increasingly rated as a companion dog, around 50 being newly registered with the Kennel Club each year. Having lost their role, the future of the breed, despite their use in minkhound packs, needs care. Twenty years ago, I wrote of my worries about their becoming in time, over-coated, featuring giant ears, of a standard colour and no longer prized as a sporting scenthound breed in the field. From their long and mixed ancestry, it would be a tragedy if their appearance became increasingly exaggerated, as so often happens with longer coated and longer eared breeds.

Rightly, in these times, the otter is no longer hunted. But it is easy to overlook the enormous damage inflicted on fish stocks by otters in past times, when fish was a far more important source of human food. The ancient fish ponds represented the freezers of today and were often 'holding' pools for fish caught elsewhere but not needed immediately for the table. Wild creatures raiding these stocks like the cormorant, the heron and the otter were regarded as vermin - a threat to the well-being of humans. The otter was subsequently hunted for sport but the kill ratio, relative to that of other country sports, was low. Parson Jack Russell, of eponymous terrier fame, stated that he had hunted over two thousand miles before encountering his first otter, even though the ground was being hunted for them throughout this distance. The otter's lifestyle did not make hunting easy. Nowadays the mink, even with a different modus vivendi from the otter, is similarly difficult to catch.

This means that hounds used to hunt mink have to be every bit as determined as those formerly used to hunt otter. They also need the anatomy to succeed in the hunting field. The standard of mouths, dentition especially, can deteriorate away from the packs; strong teeth, even teeth, and a scissor bite are all important in a hound. Variation in shoulder height is not a bad fault in scent hounds, where packs are bred to suit country, as long as the hound is balanced, free-moving, vigorous in action and not clumsily cumbersome through being too rangy. A fault to be penalised in any scenthound is when depth of rib does not reach back the whole length of the ribcage; lung room is vital. Dumfriesshire Cypher at Trevereux is a good example of a balanced well-proportioned Otterhound. It is pleasing that the breed standard permits all recognised hound colours, which must mean scenthound colours; liver and white is not permissible in the breed but is found in Whippets and Greyhounds away from the show stock.

In his 'Rural Sports' of 1870, Delabere Blaine records, on the subject of otter-hunting: "Dogs of every variety were also employed, and the whole rather resembled a conspiracy than a hunt...it is but seldom that we meet with an organised and in-and-in bred pack...Dwarf foxhounds, crossed either with the water spaniel, or with the rough wire-haired terrier, are used; but the best otter-dog, in our opinion, is that bred between the old southern harrier and the rough crisp-coated water spaniel, with a slight cross of the bull breed to give ferocity and hardihood." That informative account reveals at once the mixed blood behind today's Otterhound, as well as a disregard for pedigree, the sacred cow of the last century.

Sir John Buchanan-Jardine, in his 'Hounds of the World' of 1937, states that there was really no true breed of Otterhound before 1880. There were of course precious few true breeds of dog at that time by the judgement of today's five generation pedigree. I suggest that Otterhounds (named as a function not a breed) were dogs bred mainly from scenthound and water-dog blood and then perpetuated as the type we recognise today. The word otterhound once described any type of hound employed in that sport rather than a distinct breed. As a breed, the Otterhound is only still here today because of the vision, dedication and enterprise of a relatively small number of devotees. It is their work which has saved a distinctive British sporting breed from extinction.

It is not the job of the Masters of Minkhounds to conserve the purebred Otterhound; it is their job to control the menace of mink wherever that considerable threat to wildlife exists. If they happen to use some purebred Otterhounds for this purpose so much the better. The fate of the breed of Otterhound now rests with show ring breeders. It is a challenge and a considerable responsibility. Otters no longer pose a threat to our larders and are rightly conserved. So too must be the hounds which once hunted them, they are an important part of our sporting heritage. If we do not respect their sporting past and only breed them for their coats, the 'uniqueness' of their ears, a 'very loose and shambling' gait and 'exceptional' stride, as their breed standard demands, then we will be betraying the work of past breeders like Captain Bell-Irving with his renowned Dumfriesshire pack. May Otterhounds whether in minkhound packs or in the show ring go from strength to strength, a distinctive hound well worth saving. But so too are the other packhounds.

Why favour a scenthound from Sweden, like the Hamiltonstovare, when we have superlative and very similar hounds here like the Studbook and West Country Harriers? Why import a Grand Griffon Vendeen when we have the highly rated Welsh Hound available, of comparable type? Why, if you fancy the Basset hound, not go for the delightful little scent hounds developed as the English or Hunting Basset? What are the advantages of the Grand Bleu de Gascogne over our steadfast and long-proven Staghound? And have those now bringing in the Segugio Italiano ever seen a Trailhound in Cumbria, they really are something special. They race rather than hunt, they run freely rather than as a pack, but their genes are so valuable. They have Pointer blood in them; their breeders sought performance from superb hounds, not pure-blooded fading stock, losing virility, yet still bred in a closed gene pool for 'old times sake'!

Perhaps the best way of ensuring that there is a future for our distinguished varieties of packhound is sustained moral support for the packs, financial support for the Countryside Alliance, allied with indefatigable campaigning for the dreaded Act to be removed from the statute book. Hitler, being a Socialist, banned foxhunting in Germany as a way of punishing the landed classes. His work is continued by today's socialists, but who is punished the most? The dogs of course. Those who breed dogs need an incentive. Those who breed superlative dogs need motivation. Let's keep the bloodlines going - and the campaigning.