70 THE NORTH AFRICAN LURCHER

THE NORTH AFRICAN LURCHER

by David Hancock

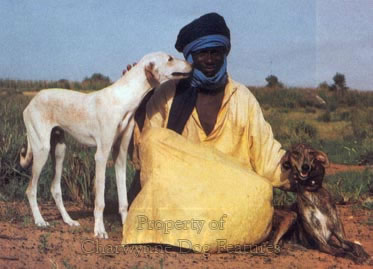

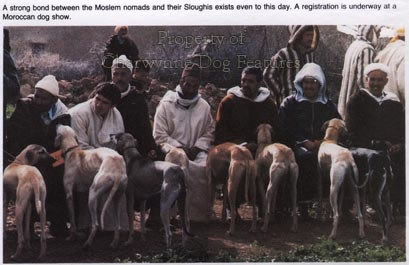

For the name of one sighthound breed to sound almost the same as that of a sister breed doesn’t exactly help discussions about the two breeds. And they are now two distinct breeds: in the pedigree world we have smooth and feathered hounds registered as Salukis, with the smooth-coated Sloughi (from North Africa) listed as a separate breed. The Arabs there however referred to them as mogrebi (magreb) or western. The Tuareg Sloughi, sometimes known as the 'oska', is classified separately in some countries as the Azawakh Sloughi, from the valley of that name in Mali and Niger. This can lead to further confusion as the Azawakh and the Sloughi are separate breeds too. The Moroccan Sahara may well be the last refuge of the true Sloughi, conserved by the nomadic tribesmen of those areas yet unaffected by the remorseless spread of the desert and commercial gazelle-hunting using motorized methods. In the settlements they have been crossed with herding or watchdog types to prevent the ravages of wild pig or jackals.

For the name of one sighthound breed to sound almost the same as that of a sister breed doesn’t exactly help discussions about the two breeds. And they are now two distinct breeds: in the pedigree world we have smooth and feathered hounds registered as Salukis, with the smooth-coated Sloughi (from North Africa) listed as a separate breed. The Arabs there however referred to them as mogrebi (magreb) or western. The Tuareg Sloughi, sometimes known as the 'oska', is classified separately in some countries as the Azawakh Sloughi, from the valley of that name in Mali and Niger. This can lead to further confusion as the Azawakh and the Sloughi are separate breeds too. The Moroccan Sahara may well be the last refuge of the true Sloughi, conserved by the nomadic tribesmen of those areas yet unaffected by the remorseless spread of the desert and commercial gazelle-hunting using motorized methods. In the settlements they have been crossed with herding or watchdog types to prevent the ravages of wild pig or jackals.

As with all hunting dogs bred by primitive people, only the very best were bred from and to become the very best they had to cope with a climate and terrain which could not have been more testing. Now they will have to face ‘urban improvement’, veterinary ‘care’ and its annual inoculations, modern convenience dog food and being bred wholly on appearance, each one an apparen t kindness, every one a potential threat. Thankfully, the breed has attracted some sensible level-headed fanciers, keen to perpetuate what is a distinctive and admirable breed of sporting dog. I soon realized the essential differences between this breed and its sister sighthound breeds, the Saluki and more importantly the Azawakh, so similar at a glance, so dissimilar in key details. All three breeds have to run fast – for quite a long time, against their most sought-after quarry – the gazelle family.

t kindness, every one a potential threat. Thankfully, the breed has attracted some sensible level-headed fanciers, keen to perpetuate what is a distinctive and admirable breed of sporting dog. I soon realized the essential differences between this breed and its sister sighthound breeds, the Saluki and more importantly the Azawakh, so similar at a glance, so dissimilar in key details. All three breeds have to run fast – for quite a long time, against their most sought-after quarry – the gazelle family.

A distinctive feature of the African sighthounds is the prominent haunch bones. Many Arab hunters will automatically place three or four fingers on the four vertebrae between the hook (hip) and pin-bones to assess the hound’s potential for speed in the chase. Sloughis always look shorter bodied than their Saluki cousins and lack the extremely prominent pin-bones of the Azawakh. The Sloughi has an almost level topline and moderate angulation in the hindquarters, with flatter less-bunched muscles than say the Greyhound. Magreb Sloughis tend to move with their heads low, with some show ring judges, more familiar with the flashier breeds, questioning the reason for this. For me it’s a more workmanlike gait. The desert-bred Sloughis can feature more than one type of foot, with a wider cat-foot, unusually for a sighthound breed, now being favoured, with well-arched toes and thick pads. The hocks are set low, and, unlike the Azawakh, the tail is carried low on the move. Their gait looks effortless, harmonious and economical.

Our Kennel Club recognizes the breed, describing it as having a dignified bearing, a ‘noble haughtiness’ and an extremely expressive face. Thankfully, it also looks for a racy and strong breed without coarseness and asks for the elongated hare-foot and a long well-developed second thigh, predictably in a sighthound breed. I saw a striking red Sloughi at a World Dog Show a few years ago, with sooty markings on the feet, under the tail and along the tips of the ears, the ‘charbon’ or charcoal coat, strangely being lost in their native country. Not surprisingly, the sandy dogs are favoured in the desert areas and the brindles, often with a black mantle, in the mountains, where they hunt wild pig, the bigger deer and even jackals. I believe some continental enthusiasts have tested their stock at non-commercial racing tracks, as well as using them in lure-coursing. This may not please the purists seeking to preserve a hunting dog but, for me, some use is always better than no use.

For lurchermen, this breed is of interest; in their homeland, they are expected to locate, stalk, pursue surreptitiously, then chase and seize their prey, rather than just race after it once sprung. They are never expected to kill their quarry, wounded game often being kept alive to retain its food value over time in a hot demanding climate. Slower than a Greyhound and looking less muscular, the Sloughi has greater stamina and certainly greater robustness in extreme heat. Compared to a Greyhound, the Sloughi is built more on a square than a rectangle and the ears are longer and droopier; white Sloughis are not favoured, but, unlike the Saluki, brindle is. The Saluki has been dubbed the Persian sighthound and the Sloughi the Arab sighthound; despite their obvious similarities, when you see the two breeds side by side, you soon see the two distinct breeds. Sadly, many of these ancient hunting dog breeds will no doubt be lost to us in the coming years and with them will go part of us too.