26 ADMIRING THE 'NIP 'N' DUCK' DOGS

ADMIRING THE 'NIP 'N' DUCK' DOGS:

the cattle-drivers; the hoof-dodgers...

by David Hancock

“ In bygone days the Welsh shepherds were accustomed to use a dog called a ‘heeler’, whose duty it was to drive the sheep away from the lowland pastures and force them back into the hills, the lower feed being reserved for the winter, when the hills were out of reach because of snow. These were mostly curs who bit the sheep and drove them off by force, but now the Welsh usually use their old dogs – the Bob-tails – who drive the sheep in any direction the shepherd wishes, and who can attain to a very high degree of perfection through their training.”

“ In bygone days the Welsh shepherds were accustomed to use a dog called a ‘heeler’, whose duty it was to drive the sheep away from the lowland pastures and force them back into the hills, the lower feed being reserved for the winter, when the hills were out of reach because of snow. These were mostly curs who bit the sheep and drove them off by force, but now the Welsh usually use their old dogs – the Bob-tails – who drive the sheep in any direction the shepherd wishes, and who can attain to a very high degree of perfection through their training.”

From Collies and Sheepdogs by WL Puxley, Williams & Norgate, 1947

I first became aware of the heeler's skill in an unusual way: playing football with a fellow twelve year old who had a Pembrokeshire Welsh Corgi. The dog 'played' football with us, and every time it was threatened by a swinging foot, it flattened instinctively and the foot cleared its head. This was done with remarkable timing. I was impressed; later on, when this dog was mated to a local terrier, I obtained a pup, such was my admiration. This 'drop-flat' technique is a vital survival technique when back-kicking hooves respond to a small dog's quick nip. Clever experienced heelers will nip the rear foot that the cow is standing on, rather than the one free to kick. The approach is nearly always from behind: a quick nip and away. Watching a farmer drive cattle up a ramp at the Bath and West Show, many years ago, using a small terrier-like dog, I asked him what kind of dog he had; he replied that ‘she’s a nip ‘n’ duck dog’. It’s an instinctive inherited skill related to the dog’s size and agility. My Border Collies could drive cattle, heeler-fashion, but found moving horses too perilous. An Italian colleague however has told me of collie-like dogs there quite able to move or round up horses without mishap, but they were specialists. I have seen spitz-type ‘sheepdogs’ rounding up ponies in Iceland using this technique.

This heeling skill was valuable when cattle needed to be moved: in markets or when loading lorries or railway trucks. Short-legged, terrier-like heelers were not an unusual sight in Britain in the last two centuries. If they had been gundogs or hounds whole libraries would be filled with tales of their deeds. But they were used by shepherds and stockmen not squires and little has been recorded of them. But when, as a student over sixty years ago, I had summer jobs on farms, it was not unusual to come across small nondescript foxy-headed dogs working cattle. I was reminded of them a few years later when, on an expedition to Norwegian Lappland, I came across Buhund-type dogs on the farms there and Lapphund-type dogs accompanying the Lapps on reindeer drives. The Germans have lost their heeler: the red-brown cattle dog known as the Siegerlander Altdeutsche Hirtenhund or Kuhhund (cowdog).

Dogs of the Vikings

There has been speculation that the Welsh Corgis were taken to Wales by Viking invaders, with the Vallhund of Sweden identified as the source. I am not aware of the 'nip and duck' instincts of Scandinavian breeds, like the Vallhund, the Buhund or the Lapphund, but the Vallhund, whilst having its own distinct breed-type, is remarkably similar to the Pembroke Welsh Corgi. The Senjahund of Finmark is noitceably similar to our surviving English heeler, the Lancashire breed. Pastoral breeds accompanied migrants perhaps more than other types, rivalled only by hounds in value. It is easy to spot British influences in pastoral dogs used in former colonies. I have seen working sheepdogs here that could easily be taken for Australian Cattle Dogs or Australian Shepherds. These Australian dogs are covered later. When sheep were traded, the sheepdogs were often traded with them. In 1982 the Smithsonian Magazine in the United States produced a theoretical model of neoteny in dogs that indicated the development of the dog in various stages throughout domestication. This study showed heelers, huskies and corgis in the first move away from the wild dog, followed by the header-stalkers, the hunters and herders, then the other types, with the flock protection dogs, with their blunter heads and drop ears, a much later development. Head shape and ear carriage can have an influence on capability.

Black Mountain Dogs

Here is a mental exercise for all owners of Corgis, Lancashire Heelers and Australian Cattle Dogs. Imagine going into a field of hefty lively bullocks, then getting down on your hands and knees and then picture the menace faced by your dogs when the cattle surround and threaten you. I write this from my memory of a story told to me on the Black Mountain on the Herefordshire/Welsh border, when I was researching the bob-tailed heelers found there. A cattle farmer told me of when he once had a diabetic attack when in a field containing twelve well-grown bullocks. He 'came to' surrounded by determined bullocks but protected by two of his heelers. Lying vulnerably on the ground, he saw the menace his dogs experienced every day, and, for the very first time, from their perspective. This experience gave him a new respect for his agile, steadfast and highly focussed dogs. Every year in Britain dog-walkers are harmed by defensive cows, usually with calves, when walking in pastureland.

On the Black Mountain, these dogs were not to be trifled with; I was warned not to get out of my car when visiting farms guarded by them, until the farmer emerged to control them. The lady photographer, sent by the magazine that commissioned my article, ignored or forgot this advice and sacrificed a nearly-new pair of wellies! These dogs lived on farms that gave the word remote its full meaning. Without mental toughness and great agility they would never survive their calling. Any 30lb dog facing a one-ton beast has my admiration; facing a dozen, with horns as well as hoofs, takes a very special kind of dog. Dogs serving man by herding horses, driving cattle or coralling wild bulls survive through their great agility, but they are chosen for their courage. Without courage, they wouldn't be exercising their agility. They are remarkable dogs.

Cur Dog Heritage

We tend to use the word 'cur' in a derogatory manner these days, but the word was used to describe a nondescript working dog rather than a definite type. In The Sportsman's Cabinet of 1803, such a dog was described as "In colour the Cur is of a black brindled or of a dingy grizzled brown, having generally a white neck and some white about the belly, face, and legs; sharp nose; ears half pricked, and the points pendulous; coat mostly long, rough, and matted, particularly about the haunches, giving him a ragged appearance, to which his posterior nakedness greatly contributes, the most of the breed being whelped with a stumpy tail." That sums up rather well many of the dogs I saw on the Black Mountain; researchers should never dismiss the word 'cur' as just derogatory.

The Welsh Heelers

In 2012, there were only 371 Pembrokeshire Welsh Corgis newly registered with the Kennel Club, and just 108 of the Cardiganshire variety. Originally classified as one breed, with only 10 being first registered in 1925, on their recognition, in 1950, there were well over 4,000 Pembrokes registered but only just under 170 of the Cardigan variety. Statistically it could be argued that the latter is maintaining its position better than the former, but it is the Cardigan that is listed as vulnerable. Patronage from the royal family led to the astonishing rise in popularity of the Pembroke dog and it has retained a steadfast bunch of fanciers. This Welsh heeler has kept its perky nature and natural assertiveness, but has lost some of the ruggedness of the earlier types. It takes courage and technique to drive cattle, a dog lacking agility being at a distinct disadvantage. Nipping a one-ton bull then avoiding its resultant kick demands special qualities.

The origins of such heeler-cattle dogs are often the subject of fierce debate and remarkable ignorance from the strangely-revered dog writers. EC Ash, in his Practical Dog Book of 1930, wrote: "...they are a cross of Shetland Sheepdog with the Sealyham Terrier, and possibly Border Terrier..." But nine years later, was writing: "I am of the opinion...that the Welsh Corgi (Pembroke) is an Alsatian cross." About that time, Theo Marples was writing: "Probably the Welsh Sheepdog and the Bull Terrier had a hand in his making." Clifford Hubbard however, who made a comprehensive study of the Welsh breeds, linked the Pembroke variety with Flemish weavers who settled in the Haverfordwest area in the eleventh century. He considered that these migrants brought their Schipperke-like dogs with them to provide an essential ingredient in the emerging breed. Hubbard knew a great deal about both Welsh dogs and pastoral dogs across the globe.

Comparable Types

We tend to think of the Schipperke as a solid-black, tail-less dog, associated with Belgian barges and a breed title derived from 'little skipper'. But there are solid fawn and solid blue varieties, some with tails, and another school of thought linking them with dwarf Groenendaels, with a breed title derived from 'little shepherd'. This has some appeal for me; I see distinct resemblances between the Schipperke, the Norwegian Buhund, the Iceland Farm Dog, the Norwegian Lundehund, the Norrbottenspets and the Vallhund of Sweden, the West Siberian Laika and the Corgis of Wales. There is a corgi-like breed in Croatia, called the Medi, already saved from extinction and being shown. It is always worth keeping in mind that useful dogs travelled with tribes or migrants across many centuries and across many borders.

The English Heeler

But what about the only surviving English heeler breed, the Lancashire Heeler? With just over 100 being registered annually this breed now appears to have been saved and have a sound future. This is very good news, firstly because we have lost too many of our native pastoral breeds, and, secondly because this is a breed well worth saving. A foot high, smooth-coated, black and tan or liver and tan, lively and perky by nature, they represent an ideal companion dog for many households. I do hope the show ring fanciers keep faith with the historic design of this breed and not produce, in time, Dachshund-like specimens with snipey jaws, bent legs and too low-to-ground a build. This is essentially a natural unexaggerated working breed, deserving to be conserved as just that. A specialist show judge for Lancashire Heelers at Crufts in 2013 concluded that: “There is still a bewildering variation in type in the lower classes, but there were enough compact exhibits with level toplines and high set tails for me to end up with a really exciting line-up in both sexes. I was delighted too that for the first time when judging the breed, all the exhibits appeared sound and not one of them hopped.” There is cause for enthusiasm over this breed’s future there. From the ringside, I like the look of Ch Doddsline Kristen, and his progeny. But the last two decades have not been good for British heeler breeds.

Heelers on Show

The comments by judges on the three British heeler breeds in recent years provides an immediate and expert view of these breeds and the state of them today. The Crufts judge of Pembroke Welsh Corgis in 1997 recorded: “Presentation was very good, sometimes too good, however the breed in general has a lot of problems, the main ones being movement, toplines and feet. Too many people are running after the latest winning dog without any thought as to how it will fit in with their own breeding plan. This results in the vast type variances we are seeing and the poor movement…” The Crufts judge of Cardigan Welsh Corgis in 1995, wrote: “The main problem however is rear construction and rear action, too many lack the drive and follow through that are a must in a working dog. They would not last on the hill pastures which they used to work and the old farmers would give them short shrift…” The Crufts judge of Lancashire Heelers in 2002 wrote: “…movement is still poor, we must never lose sight of what this dog was bred for…” In 2003, a Championship Show judge recorded on Cardigan Corgis: “I was somewhat disturbed to see so many straight fronts and bad shoulder placements and hope we can focus on returning the type and soundness we had a few years ago.” The Crufts qualifiers of the foregoing decade would have been bred from, whatever their quality, and produced the dogs reported on here.

Built-in Flaws

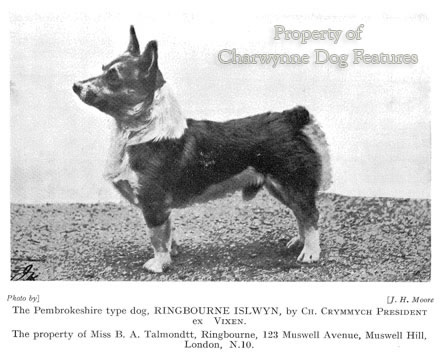

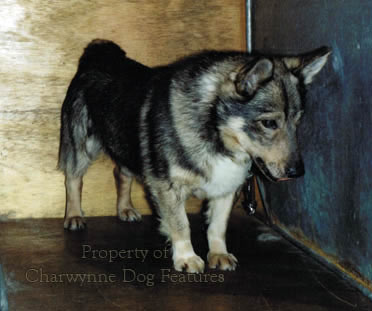

A Lancashire Heeler judge, at a 2003 show recorded: “…there is cause for concern as I think fronts are getting worse…for an active working breed conformation and soundness must come first.” But does it? That same year, a Pembroke Corgi judge gave the view that: “Movement was bad on some (both ends), poor shoulders too…Where are those good old breeders?” Four years earlier, a Cardigan Corgi judge (at LKA) had concluded: “One thing which seems apparent in the breed today is lack of length of stride, the Cardigan is a herding dog and should be able to outpace the normal walking pace of its owner. Unfortunately this is not always the case and stilted hind action is far too prevalent; poor conformation and movement lacking drive was seen in many exhibits…” and, at a different show: “I find it very difficult to understand why someone would want to show a dog that does not conform to the Breed Standard in breed type and just as importantly movement. If poor specimens are continually used in breeding programmes, i.e. poor movers and bad toplines – which now seems to be the norm when you look around - I think we can say goodbye to the breed as we have known it.” That makes disturbing reading, coming as it does from an accepted expert on the breed. It is not as though such faults had not been pointed out in the past, as the two images below, of 1934, illustrate.

Perpetuating Faults

In 2005, a Lancashire Heeler judge concluded: “What on earth has happened to this lovely breed?…I find it hard to believe that the breeders have lost the plot so completely. I was startled at the lack of quality which was here today. Dogs of all shapes and sizes, too light boned, too big, badly constructed, indifferent heads, eyes and expressions, appalling fronts…Fronts are the worst I have seen in the breed…I think the breeders need a wake up call…” In 2009 the Crufts judge of Pembroke Corgis wrote: “Last year after Crufts, Albert Wight (the 2008 Crufts judge) had some harsh words to say about the breed and I must admit I can see his point. I know it’s easy to romanticize the past but remembering the 70s and early 80s, the ‘Yorkshire’ era with all those wonderful tricolours…it’s hard to deny that we’re not going through a vintage period in the 00s”. If you consult such reports on the British heeler breeds, it is clear that there is a discernible lack of wisdom within the breeds and this is alarming. With registrations falling and judges voicing considerable disquiet, there is much to be done to safeguard the future of these fine breeds; a clear statement setting out what a working dog needs to function, back to basics if you like, is desperately required.

Cattle-dog Heritage

The larger cattle dogs overseas are well worth studying. It is interesting that dogs used with cattle can vary from those substantial enough to impose their will, like the Rottweiler, the Fila breeds - the Fila de Sao Miguel for example, the Presa breeds - the Perro de Presa Mallorquin/Ca de Bou or cow-dog of Mallorca, (Fila and Presa identifying the 'gripping' breeds), the Bardino Majero of the Canary Isles and the Perro Cimarron of Uruguay, to the little heelers. All these dogs need considerable courage but the little breeds especially so. They combine skill with guts. As long as man needs beef and milk, he will need clever, brave dogs to support him. Butchers may no longer need strong-headed dogs to pin cattle at abattoirs or markets and the droves have long lost their role. But stockmen in many countries still need cattle dogs, dogs agile enough to dodge lashing hooves and sometimes thrusting horns too, yet brave enough to undertake the task in the first place. These are not just another breed or collection of breeds. They are very remarkable dogs. As the lifestyle of modern man heads towards total urbanization, sporting and pastoral breeds face an uncertain future. We dispense with their skills at our peril; it would foolish indeed to assume that the uncertainties of the future will not in any foreseeable circumstances present a need of such unique talents.

It may be that an international organization of pastoral breeds is called for; most countries developed their own breeds in this field and common challenges have to be faced if a sound future for such admirable creatures is to be planned. I would hate to see brave and talented dogs like these wholly unemployed and just left to fade away. Cattle dogs have never enjoyed noble patronage, featured in fine art or carved a niche for themselves away from the pastures. That may not strengthen their image but should not weaken their case for conservation. The Filas or holding dogs in particular face serious threats in the developed world as ignorant law-makers punish them for the misdeeds of their owners. Yet from the stock-pen to the boar hunt such dogs merely did man's bidding; they are well equipped to continue this in many different ways for a long time to come.