23 THE DROVERS AND THEIR DOGS

THE DROVERS AND THEIR DOGS

by David Hancock

“Drovers’ dogs are singularly prompt in their actions, and all who have watched them in the crowded, noisy, tumultuous assemblage of man and beast, that used weekly to occur in Smithfield, must have observed their intelligence and courage. Nor in the busy streets of London, through which drove after drove of cattle were taken, could the same qualities fail to be noticed by any sagacious looker-on. These dogs were accustomed to bite severely, and always attacked the heels of the cattle, so that even a fierce bull was easily driven by one of them.”

“Drovers’ dogs are singularly prompt in their actions, and all who have watched them in the crowded, noisy, tumultuous assemblage of man and beast, that used weekly to occur in Smithfield, must have observed their intelligence and courage. Nor in the busy streets of London, through which drove after drove of cattle were taken, could the same qualities fail to be noticed by any sagacious looker-on. These dogs were accustomed to bite severely, and always attacked the heels of the cattle, so that even a fierce bull was easily driven by one of them.”

From Dogs and Their Ways by Charles Williams, 1863.

The Drovers and Their Dogs

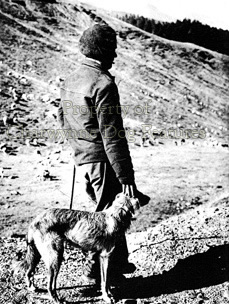

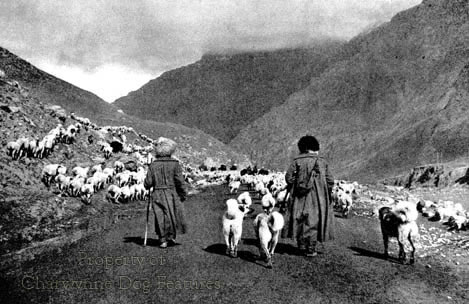

“…for centuries, at least from the time of the Norman conquest to the establishment of the railways, the most important long-distance travellers were the drovers…they formed great cavalcades that blocked the way for other travellers for hours at a time…if farmers did not want their cattle to join the drove they had to make sure they were safely enclosed…Some parts of the drove-ways were also used to transport pigs, sheep, geese and turkeys, and these animals also had to travel great distances.” Those words from Shirley Toulson’s The Drovers (Shire Publications, 1980) provide an immediate concept of the significance of historic markets and the total reliance on dogs to get the livestock to market. It’s difficult to visualize nowadays six thousand sheep being moved on foot in more or less one huge flock from east of the Pennines to the markets of Norfolk and Smithfield.  It’s not easy to think of thousands of cattle, sheep and even geese being shepherded by a small number of dogs from remote rural pastures along established drove-roads to city markets – and the dogs either accompanying the mounted drover homewards or then being left to find their own way home. These were very remarkable dogs.

It’s not easy to think of thousands of cattle, sheep and even geese being shepherded by a small number of dogs from remote rural pastures along established drove-roads to city markets – and the dogs either accompanying the mounted drover homewards or then being left to find their own way home. These were very remarkable dogs.

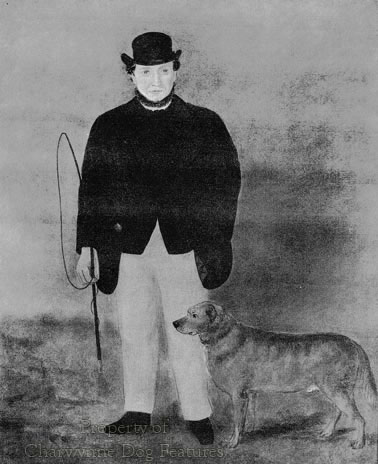

In his Cynographia Britannica of 1800, Sydenham Edwards writes, of the drover’s dog: “…he appears peculiar to England, being rarely found even in Scotland. He is useful to the farmer or grazier, for watching or driving their cattle, and to the drover and butcher for driving cattle and sheep to slaughter; he is sagacious, fond of employment, and active; if a drove is huddled together so as to retard their progress, he dashes amongst and separates them till they form a line and travel more commodiously; if a sheep is refractory and runs wild, he soon overtakes and seizes him by the foreleg or ear, pulls him to the ground. The bull or ox he forces into obedience by keen bites on the heels or tail, and most dexterously avoids their kicks. He knows his master’s grounds, and is a rigid centinel on duty, never suffering them to break their bounds, or strangers to enter. He shakes the intruding hog by the ear, and obliges him to quit the territories. He bears blows and kicks with much philosophy…” Those picturesque words are a concise summary of the dogs’ purpose, as well as showing their prowess as heelers too.

In his The Dog of 1854, Youatt wrote, on the drover’s dog: “He bears considerable resemblance to the Sheepdog, and has usually the same prevailing black or brown colour. He possesses all the docility of the Sheepdog, with more courage, and sometimes ferocity.” The drover’s dog would have needed ferocity to keep an endless stream of village curs from attacking the flock, great courage in facing every kind of obstacle and threat en route to the ‘fattening fields’ and the docility to obey every command from the accompanying drover whilst ignoring rustlers, thieves or the wrath of inconvenienced citizens finding their path blocked. Such dogs had to think for themselves, in the modern idiom, ‘think on their feet’. From that background come the gifted sheepdogs of today.

In his British Dogs of 1888, Hugh Dalziel wrote: “In all parts of England and Scotland I have seen drovers, and narrowly scanned their dogs, and I have come to the conclusion that no distinct breed can be justly described as the Drover’s Dog, but that the latter, like the poacher’s dog, the Lurcher, may be compounded of many varieties, the drover utilising for his purpose the kind of dog that comes most readily to hand.” These few words on such important dogs indicate the wide gulf between the educated classes and the peasant-shepherd over dogs; the better-off, especially the landed gentry sought style and followed fashion in their gundogs and hounds. The peasant-shepherds needed performance and were content with utility in their dogs. In books on dogs in the 19th century the pastoral dogs were rarely covered in any detail or indeed accuracy.