16 THE PRESERVATION OF TYPE IN PASTORAL BREEDS

THE PRESERVATION OF TYPE IN PASTORAL BREEDS

by David Hancock

Loss of Type

Loss of Type

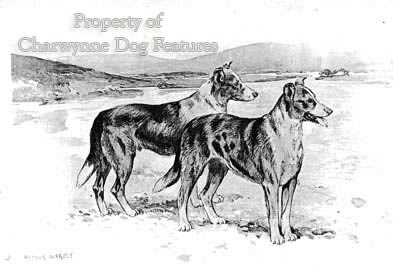

What is the correct type for each of our native pastoral breeds? Is the less refined head illustrated in the trials dogs of, say, the 1930s the true type for the Border Collie breeders to exemplify? Is the type shown of several of our native breeds, say, in the accurate depictions by the artist Arthur Wardle in his sketches of the late 1800s? He was extraordinarily gifted in capturing breed type in his work on dogs and for this was favoured by many late Victorian and then Edwardian writers and publishers. Sometimes loss of type is easier to spot than the preservation of genuine type. But what exactly is type? The KC defines it, in its Glossary of Terms, as ‘The characteristic qualities distinguishing a breed’. But are those qualities physical, mental or in temperament? Baker, in his The Collie of 1900, wrote that: “It is extremely difficult to define in words the general outline and symmetry of a Collie, but it may be summed up in one word ‘type’.” Again, not conclusive, precise or particularly instructive. My definition would be on these lines: Type is the manifestation in a breed of those particular innate physical and mental characteristics that, without exaggeration, distinguish the traditional form that a breed should take. In using these words I am seeking to preserve and perpetuate the character and conformation that was stabilised and then established when distinct breeds evolved – nearly always in pursuit of a specific function. Every breed needs type to define its identity.

In 2011, the fanciers of the Pyrenean Mountain Dog produced a brief but quite excellent, well-illustrated brochure on their breed, valuable because of its remarkable honesty and as an admirable example to other breed fanciers whose breed has temporarily gone ‘off the rails’. In it they argue that true type and the essence of the Pyrenean is being lost in the British show ring. They stress that the show ring must not promote selection on the grounds of fashion and exaggeration. They considered that fashion was winning over true type, mainly through judges who have never learned or who have lost sight of the breed’s original purpose. They point out that over the years, the handsome, working, ‘rustique’ dog has been steadily replaced by a glamorous over-coated and back-combed dog. They remind fellow fanciers that any dog able to work on high, exposed mountainsides must have a lean and muscular build and a weatherproof coat, and they end with a plea for them to respect the ‘dog of the mountains’. I salute them for this publication and applaud their criticism of judges who resort, in their after-show critiques, to words such as ‘cobby’ and ‘upstanding’ that simply do not reflect the Breed Standard for the breed.

Over the years, however, the critiques written by judges at conformation shows have revealed the state of the pastoral breeds all too starkly, indicating not just unsound breeding but also a sad loss of basic type in so many breeds. It’s worth looking at the wording of some of these, past and present:

By William Arkwright, (a highly experienced and very knowledgeable sporting dog expert) in his judge’s critique on Collies in The Kennel Gazette of November, 1890:

SHEEPDOGS

“I thought these were wretchedly bad. I had not looked at these dogs for about eighteen months, and I was shocked at their deterioration in type, in character, and in structural formation. I fear the unfortunate sheepdog has fallen into bad hands, and very soon the true animal will be a thing of the past.”

From the annual report on Collies, written by Trefoil, The Kennel Gazette, January,1891:

“During the past year, the premier honours of the show bench have again and again gone to dogs of this greyhound type whose faces bore an inane expressionless look, whose coats were soft and woolly, their bodies weedy and supported on stilt-like legs. These creatures tell their own tale of humiliation as they gazed into one’s face with their miserable look: ‘We are being improved off the face of the earth.’ That is exactly what is going on, and breeders and judges, with a few exceptions, are joining hand in hand in the work of destruction.”

By the judge of Collies, Manchester Dog Show, May, 1888:

“The collie classes were all well filled, and there was an absence of ‘the mongrel’, only one St Bernard (or a relative) being exhibited, but many of the exhibits looked as if they had been brought up in town.”

(JJ Steward, The Kennel Gazette, June, 1888).

By SE Shirley, writing the critique on Collies at the Kennel Club’s 35th Show in The Kennel Gazette of April, 1891:

“Writing generally, I may be allowed to express a sincere hope that Collie breeders will pause before they commit themselves to so dangerous an innovation as a weak, narrow-headed, brainless Collie, the animal that of all others should excel in intelligence and capacity of intellect.”

By the judge of Bearded Collies at a Championship (Ch) Show in 2012: “I penalised wide fronts, coarse/heavy shoulders and short upper arms, these faults being commonplace in some that have been winning…Far too much emphasis is placed on looks and not on make-up”

Priority given to Type

Many breeders of pedigree dogs in Britain put 'type' at the top of their list when it comes to placing, in order of priority, their breeding desiderata. Despite that, it is disappointing to note just how many breeds have lost their essential 'typiness' over the years. Breeds like the Shetland Sheepdog, the Rough and Smooth Collies, the two Corgi breeds and the Bearded Collie get less and less like the early specimens of the breed with each generation. If you study depictions of Queen Victoria’s Rough Collie Darnley II you can see at once how this breed has been changed by show ring criteria. On the other hand, breeds like the Border Terrier, the Deerhound, the Curly-coated Retriever, the Dalmatian, the Schipperke and the Pug seem able to resist human whim and retain the truly traditional look of the breed. Exaggerations exaggerating themselves play a part, as the Collie’s head illustrates. Unwise blueprints play a role too, as the 100+ words on the head and skull of the Collie demonstrate increasingly each year. For me, there are two very simple criteria to be brought to bear here. Firstly, if you admire a breed and respect its ancestry, why make it look like something different? To do so is an entirely irrational act. Secondly, if you love dogs and one breed above all others, how can you possibly justify breeding dogs of that favoured breed with an anatomy which is not only quite unlike that of their ancestors but one which threatens their health and well-being? To do so lacks any real affection, merely indicates self-interest and the absence of any real empathy with subject creatures.

The great expert on the Old English Sheepdog, HA Tilley wrote, in his booklet on the breed (undated but Florence Tilley kindly gave me a copy in 1981) of the cramped outlook of those who maintain that this, that, or the other dog represents ‘the best type’: “Such restricted opinions are usually based on personal fancy, or an obeisance to some current fashion which pays more attention to aesthetic considerations than to utility value…If someone asked me to select for him a well-bred and trained OES, my first question would be: ‘What kind of work do you want him for?’ If the reply were, ‘General work about the farm, but more particularly for sheep’, I should then ask, ‘Is your farm dry or hilly, or low-lying and on the ‘wet side’ from late autumn to spring-time?’ If he answered, ‘Mainly high and dry,’ one would advise a dog of rather less than medium height, i.e. not more than 20 inches in height, whereas for heavier conditions a bigger and stronger one would be desirable. In either case each would be ‘true to type’, but the final choice would be determined by the nature of the surroundings in which the dog would be required to work.” Such wisdom is not common in today’s show-biased world, in which breeds are so often shaped by ‘prominent breeder’s whim’.

Poor Conformation

Type can manifest itself in movement and stance; it is unwise to try to ‘stack’ every breed identically in the ring or to expect a common gait between breeds. I have seen judges try to correct a Border Collie in the ring for proceeding in a stealthy crouch, a style totally in keeping with the breed. The Greater Swiss Mountain Dog has to have a 10:9 body length to height ratio; if not ‘stacked’ naturally this ratio is disturbed. The Shetland Sheepdog has all but lost its forechest, lying in front of the point of shoulder, but crafty ‘stacking’ can conceal this fault. I see Shelties too with their legs too short but made to stand ‘tall’. I expect to see a ‘show of pads’ when the Corgi is being moved in the ring; when it is not displayed I strive to look closer. I see GSDs over-reaching when ‘gaited’ and sometimes they even win a ticket. This is a serious fault in a working breed. But unless the dog moves crab-wise or not straight ahead, few judges penalize it. The flying trot in this breed so often conceals a multitude of flaws. The heavily-coated breeds all too often get away with poor conformation when clever ‘stacking’ before the judge conceals the position of the hind feet relative to the torso, the effortless classic Collie movement cannot take place with hyper-extension at the back. Type isn’t just about coat colour, head shape, ear carriage or set of tail.

Satisfying the Breed Standard

A number of breeds strive, through their Breed Standard’s words, to make a breed unique or ‘racially special’, as my vet put it rather cruelly recently. If you read the Standard of, say, the Old English Sheepdog, you can soon pick up such a tendency. Under Gait/Movement, these words appear: “When walking, exhibits a bear-like roll from the rear.” Some breed fanciers put a value on this when claiming it as Bobtail-type. But let another vet, RH Smythe, in his informative The Dog – Structure and Movement of 1970, comment on this: ‘In the case of the O.E. Sheepdog the reason for the roll is rather different (i.e. from that of the Bulldog, DH). In this breed exaggerated hock flexion causes the body to descend slightly on the side which carries the weight, while the opposite hock is being lifted.’ This Breed Standard, under the same heading, states that: ‘At slow speed, some dogs may tend to pace.’ Pacing, that is the hind and fore limbs on each side advancing together, is tiring, unnatural and wearing to the locomotive muscles. It is not an acceptable feature in a breed once famous for its long-distance walking feats. Type must never conflict with soundness.

Unrealistic Expectation

It is foolish to regard any dog registered with the KC as a purebred product as having true type just because it is a registered pedigree dog. Type in any breed of dog is far more subtle and a lot more elusive than that. For me dogs with the genuine look of their breed are always to be preferred to untypical specimens with "papers". Is a German Shepherd Dog with a roach back, hyper-angulation in its hindquarters and a lack of substance, with two show-ring wins and KC registration to be preferred to an upstanding, well-boned and symmetrically built dog with a level topline but no papers? Contemporary GSD breeders seem to have lost their way and it's going to take decades to restore true type to this quite outstanding breed. I wholeheartedly agree with Lady Malpas, who wrote a few years ago to one of the dog papers: "There can be no justification for any attempt, accidental or intentional, to produce different types of German shepherd." I also support the view of a GSD breed correspondent who questioned 'What has happened to this noble breed? I was brought up in the school that had as a pattern dogs like Ch. Fenton of Kentwood, Ch. Sergeant of Rozavel and dogs of similar type. My mentors told me that a good Alsatian could carry a glass of water on its back without spilling when moving...' What ever makes a breed-clique alter a breed to its disadvantage? The first show Alsatians I ever saw, as a young teenager, were from the celebrated 'of Movem' kennel and had a topline for any breeder to die for!

In Germany, the 'breed wardens' for the GSD wield enormous power. It was therefore good to read that a new (2013) breed warden has taken a long hard look at the breed and outlined his main priorities: health and agility, return to the Standard, a broadening of the bloodline basis or gene pool and reduction of inbreeding, the promotion of working ability and, significantly, opposition to the trend of breeding look-a-like 'clones', wherein every dog in the breed resembles the next one - the dreaded 'cookie-cutter' dogs. The last point is of interest; how do you breed to the Standard without producing dogs of almost exact appearance? It could lead to a temporary loss of breed type but it might also result in the best working dog physique being favoured over rows of extremely handsome identical dogs - all with the same faults..jpg)

The service to man of the German Shepherd Dog is difficult for any other breed to match. I have seen them at work and witnessed their versatility in nearly twenty different countries. I had always considered their breed type to be fixed. Unlike manufactured breeds like the Dobermann and the Leonberger, there is no risk of a strong prototypal ancestor-breed like the Greyhound or the Bulldog manifesting itself. Any breeder who tampers with a breed type long established, long accepted and long proven able to produce an intelligent, healthy, biddable dog is a dangerous, misguided maverick who should be halted in his tracks. In any breed of pedigree dog it only takes one determined breeder with more money than sense to promote his concept or a dominant clique to gain ascendancy for true type to be threatened. Breeds don't just lose type; breeders lose their way. But who lets them? The KC really must appoint Breed Councils as the guardians of each breed – it is truly a high priority.

Restoration of Type

If breed type, real breed type, not ‘flavour of the month’ or false phenotypes compounded over recent years by show ring whim or temporary fashion, actually matters, and I do believe it does, an argument could be made for ‘starting again’. By that I mean the drawing-up of the correct historical type for each native pastoral breed from the earliest depictions, principally from very old photographs, then by a programme of planned breeding, re-creating or restoring that type in each of our native pastoral breeds. When you look at the KC acceptance of a created breed such as the Eurasier and that by the FCI of the Kromfohrlander, a far stronger case could be made for the restoration of our lost native breeds, mentioned in the Preface. I see look-alikes of the Welsh Hillman, the Old Welsh Grey, the Black and Tan Sheepdog and the Irish breeds: the Galway Sheepdog and the Glenwherry Collie remarkably often; the type is clearly strongly perpetuated. It would be a fascinating project too to reproduce the lost Smooth Shetland Sheepdog; those who admire the breed but not its contemporary coat would certainly find such a scheme of interest. Perpetuating sickly or overdone pedigree breeds makes no sense at all in today’s more compassionate society. Type alone once ensured soundness because the type desired was rooted in a working not a flashy showy appearance; we owe it to our contemporary breeds to return to such a valuable breeding culture.